|

Rank /

Title /

Year | |

| 1 |

|

| 2 |

|

| 3 |

|

| 4 |

|

| 5 |

|

| 6 |

|

| 7 |

|

| 8 |

|

| 9 |

|

| 10 |

|

| 11 |

|

| 12 |

|

| 13 |

|

| 14 |

|

| 15 |

|

| 16 |

|

| 17 |

|

| 18 |

|

| 19 |

|

| 20 |

|

| 21 |

|

| 22 |

|

| 23 |

|

| 24 |

|

| 25 |

|

| 26 |

|

| 27 |

|

| 28 |

|

| 29 |

|

| 30 |

|

| 31 |

|

| 32 |

|

| 33 |

|

| 34 |

|

| 35 |

|

| 36 |

|

| 37 |

|

| 38 |

|

| 39 |

|

| 40 |

|

| 41 |

|

| 42 |

|

| 43 |

|

| 44 |

|

| 45 |

|

| 46 |

|

| 47 |

|

| 48 |

|

| 49 |

|

| 50 |

|

| 51 |

|

| 52 |

|

| 53 |

|

| 54 |

|

| 55 |

|

| 56 |

|

| 57 |

|

| 58 |

|

| 59 |

|

| 60 |

|

| 61 |

|

| 62 |

|

| 63 |

|

| 64 |

|

| 65 |

|

| 66 |

|

| 67 |

|

| 68 |

|

| 69 |

|

| 70 |

|

| 71 |

|

| 72 |

|

| 73 |

|

| 74 |

|

| 75 |

|

| 76 |

|

| 77 |

|

| 78 |

|

| 79 |

|

| 80 |

|

| 81 |

|

| 82 |

|

| 83 |

|

| 84 |

|

| 85 |

|

| 86 |

|

| 87 |

|

| 88 |

|

| 89 |

|

| 90 |

|

| 91 |

|

| 92 |

|

| 93 |

|

| 94 |

|

| 95 |

|

| 96 |

|

| 97 |

|

| 98 |

|

| 99 |

|

| 100 |

|

Former Entries | |

| X |

|

| X |

|

| X |

|

| X |

|

| X |

|

| X |

|

| X |

|

| X |

|

| X |

|

| X |

|

| X |

|

|

Browse Films by Title / Year / Reviews Nick-Davis.com Home / Blog / E-Mail | |

#63: The Baby of Mâcon and The Pillow Book Mâcon (UK, 1993; dir. Peter Greenaway; cin. Sacha Vierny; with Julia Ormond, Jonathan Lacey, Ralph Fiennes, Philip Stone,

Nils Dorando, Don Henderson, Celia Gregory, Diana Van Kolck, Jessica Hynes, Kathryn Hunter, Gabrielle Reidy, Jan Sepers)

Mâcon (UK, 1993; dir. Peter Greenaway; cin. Sacha Vierny; with Julia Ormond, Jonathan Lacey, Ralph Fiennes, Philip Stone,

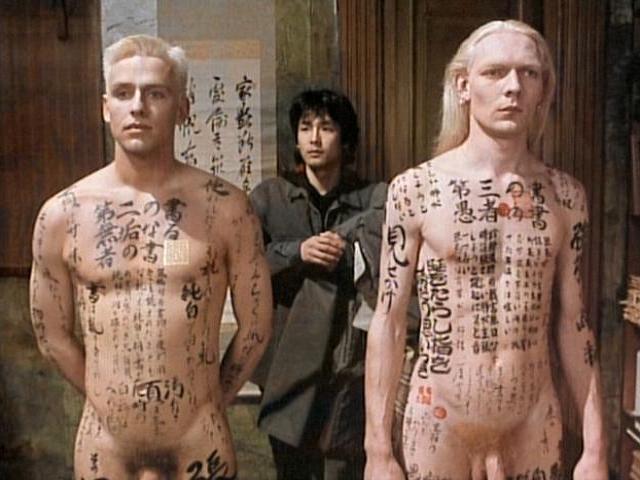

Nils Dorando, Don Henderson, Celia Gregory, Diana Van Kolck, Jessica Hynes, Kathryn Hunter, Gabrielle Reidy, Jan Sepers)IMDb Pillow (UK/Japan, 1996; dir. Peter Greenaway; cin. Sacha Vierny; with Vivian Wu, Yoshi Oida, Ewan McGregor, Ken Ogata, Hideko Yoshida, Judy Ongg, Ken Mitsuishi, Yutaka Honda) IMDb // My Page I wouldn't be surprised at all to learn that Peter Greenaway is not the child of two humans, but the offspring of a building and a painting, born on the hottest day of the year in some very, very chilly place. His cinema might be the most immediately identifiable of any English-language director, and maybe of any director, period: he doesn't seem to have seen or cared about the work of other filmmakers so much as he has traveled the world to behold giant plinths and catafalques, leafed through Da Vinci's notebooks and Euclidean proofs, and made the best of a poor situation, committing his imaginary worlds to film because it's the only form that anyone is willing to subsidize. Effectively, he's been making CD-ROMs since the days when people still bought music on cassette tapes. His images dissolve into and hyperlink to each other, massive as all creation when they aren't cropped and subdivided into defiantly atypical aspect ratios. Art, math, money, and frank sexuality intersect in his movies, just like on the internet—just like everywhere, really—except that with Greenaway at the helm, this collision of humanity's great passions winds up looking like nothing any other person would ever conceive, and perhaps not like anything that any other person would ever want to see. Greenaway leaves a lot of moviegoers cold, and conversely, some of his most ardent supporters are curators, academics, and high-cultural separatists who are rarely caught in any screening venue where popcorn has ever been sold. I almost walked out of the impeccably mounted and ferociously acted The Cook, the Thief, His Wife, and Her Lover, whose sour misanthropy seems aimed not just against people but against movies themselves. The Belly of an Architect might have been a better intro, 8½ Women might have been better consigned to the dustbin of stunted ideas, and as for Prospero's Books, though I'm now quite taken with its multi-mediated museum of Elizabethan idioms, it didn't really impress me until my third or fourth try. Despite this spotty track record, Greenaway is a director who interests me tremendously; I'm not easily put off by someone who will work this hard to make such exquisitely eccentric objects, alternately impenetrable and rife with insinuations. Twice, his epic blends of the epicurean and the rectilinear have produced something that really floored me. Go figure, then, that my favorite of Greenaway's movies, The Baby of Mâcon, is the one that's still illegal in the United States, presumably because it's the one that comes close in its esoteric way to saying something that the United States needs to hear. Julia Ormond, happening upon a director even frostier than she is, comes wickedly alive as a hot-blooded French woman in a 17th-century village beset by famine, plague, and fallow fields. The only sign of new life in Mâcon is the pristinely beautiful baby that springs, incongruously, from Ormond's obese and haggard mother; boldly braiding her own self-interest into the town's thirst for a positive omen, she claims the flaxen-haired infant as her own virgin birth, and then seduces the local bishop's icily skeptical son (Ralph Fiennes) with the brazen magnificence of her lie and the voluptuous offering of her body. Every main character is paradoxically addicted to the ideal of holiness and the spark of carnality, leading to the sorts of perverse hypocrisies and self-gratifications that, in Greenaway's films, always get you killed in an especially macabre way. If anything, The Baby of Mâcon is even more lavishly mounted than most Greenaway pageants, and even more Artaudian in its sickening climax of violence. By staging the film as a Jacobean revenge drama—Sacha Vierny's camera glides fluidly but anxiously through the tense action, the offstage grumblings, and the murmuring audience of puffy aristocrats and smudgy commoners—Greenaway poses questions about voyeurism and cruelty that encompass both his viewers and himself, further layering the implications of this scary horror-melodrama about fundamentalism, superstition, jealousy, and prurience.  After the international PR disaster of The Baby of Mâcon, Greenaway's next film was the luxuriously synesthaesiac

The Pillow Book, an absolute corker of a 90-minute movie that

unfortunately continues for 45 more minutes, working hard in the

process to numb and obliterate everything that is almost impossibly

gorgeous in the preceding material. Vivian Wu plays Nagiko, a haughty

Japanese model with an insatiable yearning for having calligraphy

painted on her skin. Wu is a shrilly maladroit presence, and the

premise wouldn't work at all if it weren't realized in such sinuous

detail, but so it is. The Pillow Book

lists two directors of photography, three production designers, four

costume designers, and two calligraphers in the opening credits, and

indeed, the movie comes closer than any other to constituting its own

elaborate, absorbing museum—one where you're encouraged to sniff and

caress the artwork, to strip the clothes off the models, to run the

paint along your tongue like it's a spice. This unparalleled

mise-en-scène, the creatively embedded frames, and the arresting sonic

mix of Japanese pop, monastic chants, and avant-garde rock together

yield a new kind of movie, a three- and almost four-dimensional

environment. Customary film grammar hardly accounts for how the movie

works, either when it's scoring or when it's flailing, and if its

structural repetitions ultimately grow a bit tedious, its fearless

peculiarity and almost aphrodisiac blend of skin, music, and curvaceous

lettering make it worth digesting in multiple doses, even if they're

small ones.

After the international PR disaster of The Baby of Mâcon, Greenaway's next film was the luxuriously synesthaesiac

The Pillow Book, an absolute corker of a 90-minute movie that

unfortunately continues for 45 more minutes, working hard in the

process to numb and obliterate everything that is almost impossibly

gorgeous in the preceding material. Vivian Wu plays Nagiko, a haughty

Japanese model with an insatiable yearning for having calligraphy

painted on her skin. Wu is a shrilly maladroit presence, and the

premise wouldn't work at all if it weren't realized in such sinuous

detail, but so it is. The Pillow Book

lists two directors of photography, three production designers, four

costume designers, and two calligraphers in the opening credits, and

indeed, the movie comes closer than any other to constituting its own

elaborate, absorbing museum—one where you're encouraged to sniff and

caress the artwork, to strip the clothes off the models, to run the

paint along your tongue like it's a spice. This unparalleled

mise-en-scène, the creatively embedded frames, and the arresting sonic

mix of Japanese pop, monastic chants, and avant-garde rock together

yield a new kind of movie, a three- and almost four-dimensional

environment. Customary film grammar hardly accounts for how the movie

works, either when it's scoring or when it's flailing, and if its

structural repetitions ultimately grow a bit tedious, its fearless

peculiarity and almost aphrodisiac blend of skin, music, and curvaceous

lettering make it worth digesting in multiple doses, even if they're

small ones. |

| Permalink | Favorites | Home | Blog |