|

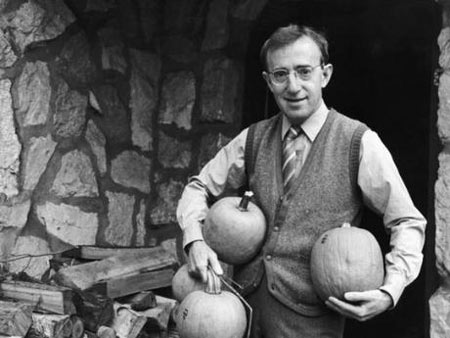

| Photo © 1983 Orion Pictures |

| Academy Award Nominations: | |

| Best Cinematography: Gordon Willis | |

| Best Costume Design: Santo Loquasto | |

| Golden Globe Nominations: | |

| Best Picture (Musical/Comedy) | |

| Best Actor (Musical/Comedy): Woody Allen | |

| Other Awards: | |

| New York Film Critics Circle: Best Cinematography | |

| Permalink | Home | 1983 | ABC |