|

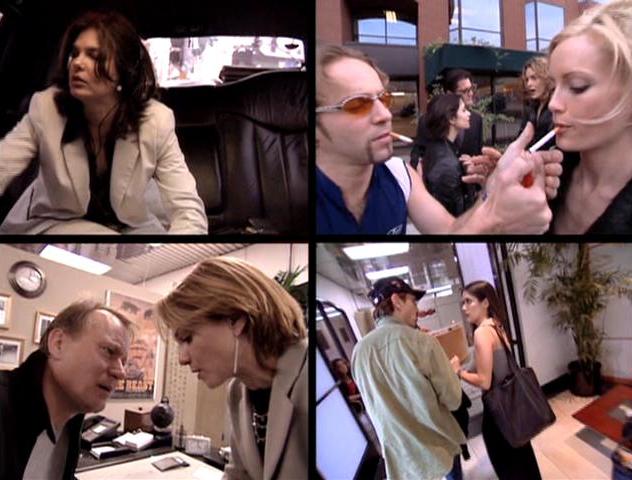

| Photo © 2000 Screen Gems/Red Mullet Productions |

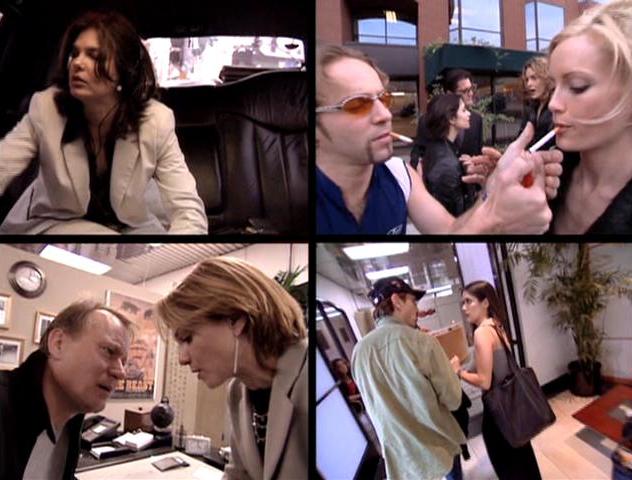

There are so many wonderful grace notes, among them the dazzling

moment where a reflective limousine window is wound down, and Jeanne Tripplehorn and Leslie Mann, one inside the car and the other on the sidewalk, sort

of bleed across each other's demarcated space and back again (neither appears in the other's corner at any other point in the movie, from what I recall).

There's another expertly orchestrated scene where two of our key players collide in the street without recognising each other, while two more gaze down

their own images in bathroom mirrors, where they are having a kind of synchronised meltdown. Wherever I'm drawn in terms of performance or story on each

viewing, I always thrill to these encounters, little jests, and orchestrated collisions—though the numerous earthquakes do get a little tiresome—and

find them a reliable justification in themselves for the whole ethos of handheld multiplicity Figgis is dabbling in. Put another way, the movie's chief

gambit encourages me to browse as much as to watch. What do you think?

There are so many wonderful grace notes, among them the dazzling

moment where a reflective limousine window is wound down, and Jeanne Tripplehorn and Leslie Mann, one inside the car and the other on the sidewalk, sort

of bleed across each other's demarcated space and back again (neither appears in the other's corner at any other point in the movie, from what I recall).

There's another expertly orchestrated scene where two of our key players collide in the street without recognising each other, while two more gaze down

their own images in bathroom mirrors, where they are having a kind of synchronised meltdown. Wherever I'm drawn in terms of performance or story on each

viewing, I always thrill to these encounters, little jests, and orchestrated collisions—though the numerous earthquakes do get a little tiresome—and

find them a reliable justification in themselves for the whole ethos of handheld multiplicity Figgis is dabbling in. Put another way, the movie's chief

gambit encourages me to browse as much as to watch. What do you think? NICK: That actually helps me a lot with the film, because I have to admit, the lack of tendentiousness made me a little leery of crediting Figgis

with saying much that is interesting about voyeurism. Neither following someone around relentlessly with a camera nor seeing two threads of the same story

at the same time necessarily amounts to "voyeurism," which strikes me as an incredibly hard notion to access without the privilege of montage or without,

ironically, a bit more distance from the characters. Our sense of being right there with them, rather than spying on them from afar, feels much less "voyeuristic"

in form than what Tripplehorn, for example, is pulling off from her limo. Though the passage when she's secretly listening in on a love-making session between

two characters transpiring behind a movie screen, on which a third set of characters is screening some footage in the southwest quadrant, and wondering what

happened to one off their key colleagues, I think the film capitalizes most fully on the structuring tension between the simultaneity of what we're watching

and the forceful disparity of what it "means" from panel to panel. The event has important reverberations, if slightly broader ones, for the fourth panel,

too.) In any event, this bravura bit of orchestration is much more interesting than, say, those four extreme close-ups you mention at around 22:00—a bit

of flash without, for me, much resonance. The film works best when the four-square approach adds to or complicates the surface tensions and power games

that the scenario already posits among these folks. I gather Figgis sketched the "script," such as it was, on sheets of music paper, and when the four quadrants

suddenly rival each other for sheer intensity, as here, the movie gives reciprocal weight to what we're watching and how we're watching it.

So much so that the "browsing" approach, which is a great word, feels newly scandalous: how dare I browse between such stark and self-abasing betrayal and

the gathering storm around she who is hearing herself betrayed?

NICK: That actually helps me a lot with the film, because I have to admit, the lack of tendentiousness made me a little leery of crediting Figgis

with saying much that is interesting about voyeurism. Neither following someone around relentlessly with a camera nor seeing two threads of the same story

at the same time necessarily amounts to "voyeurism," which strikes me as an incredibly hard notion to access without the privilege of montage or without,

ironically, a bit more distance from the characters. Our sense of being right there with them, rather than spying on them from afar, feels much less "voyeuristic"

in form than what Tripplehorn, for example, is pulling off from her limo. Though the passage when she's secretly listening in on a love-making session between

two characters transpiring behind a movie screen, on which a third set of characters is screening some footage in the southwest quadrant, and wondering what

happened to one off their key colleagues, I think the film capitalizes most fully on the structuring tension between the simultaneity of what we're watching

and the forceful disparity of what it "means" from panel to panel. The event has important reverberations, if slightly broader ones, for the fourth panel,

too.) In any event, this bravura bit of orchestration is much more interesting than, say, those four extreme close-ups you mention at around 22:00—a bit

of flash without, for me, much resonance. The film works best when the four-square approach adds to or complicates the surface tensions and power games

that the scenario already posits among these folks. I gather Figgis sketched the "script," such as it was, on sheets of music paper, and when the four quadrants

suddenly rival each other for sheer intensity, as here, the movie gives reciprocal weight to what we're watching and how we're watching it.

So much so that the "browsing" approach, which is a great word, feels newly scandalous: how dare I browse between such stark and self-abasing betrayal and

the gathering storm around she who is hearing herself betrayed?| Permalink | Timecode | Home | 2000 | ABC | Blog |