| |

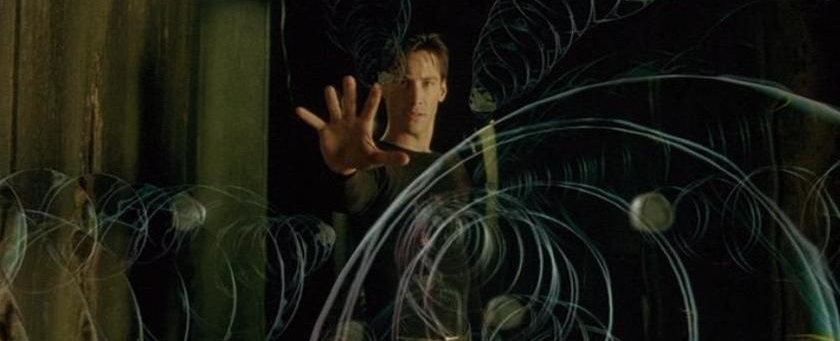

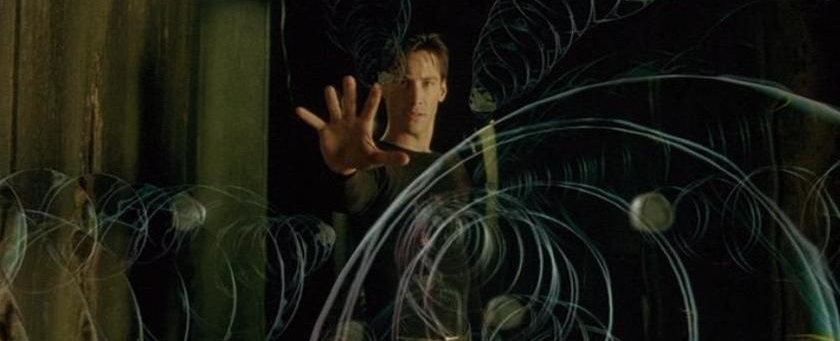

| Photo © 1999 Warner Bros. Pictures | |

| Academy Award Nominations and Winners: | |

| ★ | Best Film Editing: Zach Staenberg |

| ★ | Best Sound: John T. Reitz, Gregg Rudloff, David E. Campbell, and David Lee |

| ★ | Best Sound Effects: Dane A. Davis |

| ★ | Best Visual Effects: John Gaeta, Janek Sirrs, Steve Courtley, and Jon Thum |

| Other Awards: | |

| British Academy Awards (BAFTAs): Best Sound; Best Visual Effects | |

| Permalink | Home | 1999 | ABC | Blog |