|

Rank /

Title /

Year | |

| 1 |

|

| 2 |

|

| 3 |

|

| 4 |

|

| 5 |

|

| 6 |

|

| 7 |

|

| 8 |

|

| 9 |

|

| 10 |

|

| 11 |

|

| 12 |

|

| 13 |

|

| 14 |

|

| 15 |

|

| 16 |

|

| 17 |

|

| 18 |

|

| 19 |

|

| 20 |

|

| 21 |

|

| 22 |

|

| 23 |

|

| 24 |

|

| 25 |

|

| 26 |

|

| 27 |

|

| 28 |

|

| 29 |

|

| 30 |

|

| 31 |

|

| 32 |

|

| 33 |

|

| 34 |

|

| 35 |

|

| 36 |

|

| 37 |

|

| 38 |

|

| 39 |

|

| 40 |

|

| 41 |

|

| 42 |

|

| 43 |

|

| 44 |

|

| 45 |

|

| 46 |

|

| 47 |

|

| 48 |

|

| 49 |

|

| 50 |

|

| 51 |

|

| 52 |

|

| 53 |

|

| 54 |

|

| 55 |

|

| 56 |

|

| 57 |

|

| 58 |

|

| 59 |

|

| 60 |

|

| 61 |

|

| 62 |

|

| 63 |

|

| 64 |

|

| 65 |

|

| 66 |

|

| 67 |

|

| 68 |

|

| 69 |

|

| 70 |

|

| 71 |

|

| 72 |

|

| 73 |

|

| 74 |

|

| 75 |

|

| 76 |

|

| 77 |

|

| 78 |

|

| 79 |

|

| 80 |

|

| 81 |

|

| 82 |

|

| 83 |

|

| 84 |

|

| 85 |

|

| 86 |

|

| 87 |

|

| 88 |

|

| 89 |

|

| 90 |

|

| 91 |

|

| 92 |

|

| 93 |

|

| 94 |

|

| 95 |

|

| 96 |

|

| 97 |

|

| 98 |

|

| 99 |

|

| 100 |

|

Former Entries | |

| X |

|

| X |

|

| X |

|

| X |

|

| X |

|

| X |

|

| X |

|

| X |

|

| X |

|

| X |

|

| X |

|

|

Browse Films by Title / Year / Reviews Nick-Davis.com Home / Blog / E-Mail | |

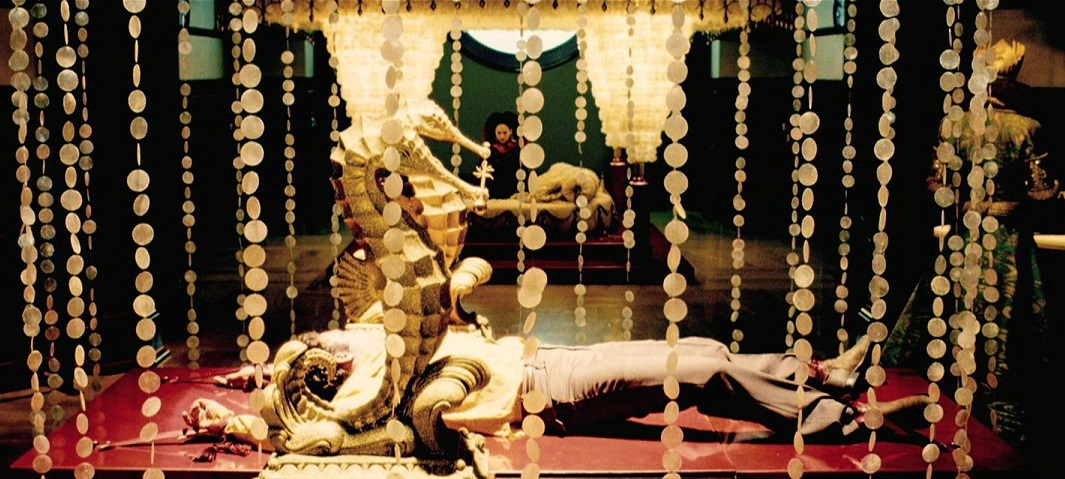

#15: The Cell (USA, 2000; dir. Tarsem Singh; scr. Mark Protosevich; cin. Paul Laufer; with Jennifer Lopez, Vince Vaughn, Vincent D'Onofrio, Marianne Jean-Baptiste, Dylan Baker, Jake Weber, Jake Thomas, Tara Subkoff, James Gammon, Patrick Bauchau, Peter Sarsgaard)

(USA, 2000; dir. Tarsem Singh; scr. Mark Protosevich; cin. Paul Laufer; with Jennifer Lopez, Vince Vaughn, Vincent D'Onofrio, Marianne Jean-Baptiste, Dylan Baker, Jake Weber, Jake Thomas, Tara Subkoff, James Gammon, Patrick Bauchau, Peter Sarsgaard)IMDb // My Full Review // Leave a Comment This entry is for my friend Juan Martinez, a great writer whose nifty and layered interventions into horror I've been enjoying all month, when he isn't freaking me the f*ck out. It's taken me fifteen years and how many viewings (eight? nine?) to acknowledge that certain aspects of The Cell are what you might call subpar. Woven into the movie is a strained, falsely protracted procedural where federal investigators say all the requisite lines ("I don't want anyone dragging their ass on this!") and require an hour of screen time inside a convoluted apparatus of intrapsychic teleportation to surmise, "Maybe I should track the company that manufactured this incongruous sheet metal/chain link/suspension apparatus, whose corporate insignia I meaningfully traced with my finger in the basement of a serial killer's modest home." The same serial killer stocks the same basement with preserved hummingbirds in bell jars and first aid cabinets with "Are You Sick?" scrawled in red on the doors, for maximum Psycho allusiveness and Cray Cray telegraphing. The biomedical research firm that has invested in a high-risk, high-overhead technology by which a semi-trained psychologist can literally travel into the minds of comatose patients has perhaps over-allocated funding to couture Bram Stoker's Body Suits. They've also been somewhat flip in recruiting their subconscious spelunker. Of all the auditioning therapists, "Catherine was the least experienced," we learn from Dylan Baker, trapped throughout the film in a prisonhouse of exposition, "but we decided, 'What the hell?'" Baker and his co-director, the resourcefully expressive Marianne Jean-Baptiste, are having trouble convincing Jennifer Lopez's Catherine that it really is better for her to travel into patients' minds than to lure them into her own, and anyway it would require months and multimillions to reverse-engineer the procedure. Helpfully, though, they have snuck some kind of Would You Like To Reverse The Feed? button into a control panel inside the airlocked teleportation chamber, which they can't access but J.Lo can. When she's had it with science and dumb feds, she HAL 9000's, overrides the system, and lays a red carpet for cinema's sickest ladykiller right into her cerebellum. The Cell requires some benefit of the doubt. But The Cell is also about benefit of the doubt, misplaced and otherwise: risking lots on dangerous research, risking more on practitioners who aren't producing, trusting that even homicidal maniacs who bleach their victims' bodies and ejaculate on their corpses have wounded, recoverable children living inside them. The movie itself is, in all senses, a spectacular result of gambling on exciting neophytes. Tarsem had directed some indelible ads and music videos, most famously the one for R.E.M.'s "Losing My Religion," before making the leap to bigger screens with The Cell. He did so with support from New Line Cinema, a historically generous backer of eccentric visionaries working at grand scales. Yes, the script comes outfitted (one might say saddled) with serial-killer tropes we've seen plenty of times, but Tarsem seizes or opens innumerable opportunities to fashion The Cell as a portal into his own imagination. They could have called it Mind Boggle. Are sequences sometimes unstructured, creating flimsy pretexts or none at all for graphic astonishments that the filmmakers cannot resist? Sure, to a point of hilarious incorrigibility: why present a simple establishing shot of an abandoned factory when you could pan over from a random tortoise nudging its way through a field? Why not insert an extreme close-up of a blood droplet bouncing a ladybug off a leaf? Eat it, ladybug! Is Tarsem's mind replete, like everyone's, with vistas and talismans he swiped from other artists, no matter how vociferously New Line trumpeted The Cell's originality? Is "Tarsem's mind" a just locution, given how pointedly The Cell showcases Howard Shore's, Eiko Ishioka's, Tom Foden's, and Michèle Burke's creativity as well? These are all fair questions and retorts, and the most exacting formalists or high-priests of narrative will quickly throw up their hands. But The Cell has always felt prodigious to me as both a conjuration of the macabre (and that's even without the theater getting hit by lightning at a key moment) and a plume of barely-filtered inspiration. This is the Cinema of Attractions, revived after a century of narrative mandates. This is a battery of creators making a mind's eye visible, exactly in sync with the story's conceit but refusing to be hemmed in by story. I rhapsodized about favorite gestalts in my original review, and even then I only covered some of them: the canopy of glowing shells, the panicked trills of orientalist pipes swirling over a Namibian sand dune, the acrobatic moves of a diabolical abductor, the shimmering aubergine curtains that turn out to be gargantuan capes. The movie giddily and repeatedly tips its vertical axis, and throws in some glass bowls of electric eels when not enough is happening for Tarsem's taste. It adds some ropey gold filigree and suppurating red thistles to the borders of the frame when a late-breaking confession scene could use some tarting up. These kinds of touches you either go with or don't—The Cell as a whole you either go with or don't—but I also reject the hypothesis that they're purely gratuitous. Take the last one. Surrounding Catherine and Carl, the alliteratively named healer and killer, with the same beautiful but unsettling embellishments, underscoring a brief moment when he's really talking and she's really listening, establishes a bond and a match between these characters, which are not the same thing. It also underscores the violence with which that bond suddenly breaks, and how quickly Catherine passes from beatific protector to my-world-my-rules vigilante-avenger (hence, the match), and suddenly back to beatific protector. Remember, all this happens in her mind. So as much as The Cell leaves itself open to charges of sensationalizing homicidal mindsets and of portraying abuse survivors as elaborately damaged goods, it also casts a rigorously skeptical eye on protagonists we're set up to root for. I floated that thesis in my first review, and though I've been told it seems overly generous, I don't concede that. The Cell makes an early point of cross-cutting between Carl's ritualized obsession with his captives and Catherine's dreamworld fixations on herself as lonely angel and a young client as deranged creature. The visual homonymy of the psychologist suspended in isolation and the psychopath hanging over his prey is hard to ignore, as are the multiple notes in the finale, from acting to costume to dialogue, suggesting that Catherine is "pretty fucking strange." Indeed, what she gleans from The Cell's long, grisly episode is that it really would be better for sick or incapacitated patients to be enveloped within her own preconceptions, rather than learning their own mental architectures, albeit at a snail's pace. Isn't this the opposite of empathy? "You can stay here with me," Catherine tells a bloodied sufferer inside her own consciousness, in full Mother Mary garb as she prepares to mercy-kill him. That doesn't seem like a great idea for her or for him. This is Clarice slaughtering the lambs herself, and pulling them into bed with her. Does The Cell pathologize feminine-coded therapy as much as it does misogynist violence? Maybe so, and it deserves pushback from viewers affronted by that implication. What I care about is that The Cell isn't just stunning to witness, it's ripe for complex unpacking: a workout for ear and eye, and for moral cogitation. When artists lean this far into audiovisual extravagance, particularly within disreputable genres, assumptions quickly arise that they can't possibly be thinking while they're dressing all those sets or traumatizing that many bodies. Even phrases like "unfettered imagination," intended as praise, can imply that Tarsem or Foden or Ishioka aren't governing their impulses at all, aren't using them toward coherent ends. So yes, The Cell is a dubious project at times, a little too ogly at albinism and desecrated femininity, not quite trusting that we'll identify eight mangled women inside Carl's mind unless Catherine whispers "His victims...," a bit overconfident that you can flood a room full of live camera equipment and survive the experience, triumphant. Eels aren't the only things that electrocute, baby. The Cell is sometimes silly. But it's not nearly as silly as some would have you believe. Looking phenomenal, looking otherworldly, doesn't mean you've turned your back on the world, or that you have nothing on your mind. Surely Tarsem agrees. J.Lo definitely agrees. I myself wouldn't know, but I learned it at the movies. |

| Permalink | Favorites | Home | Blog |