|

Rank /

Title /

Year | |

| 1 |

|

| 2 |

|

| 3 |

|

| 4 |

|

| 5 |

|

| 6 |

|

| 7 |

|

| 8 |

|

| 9 |

|

| 10 |

|

| 11 |

|

| 12 |

|

| 13 |

|

| 14 |

|

| 15 |

|

| 16 |

|

| 17 |

|

| 18 |

|

| 19 |

|

| 20 |

|

| 21 |

|

| 22 |

|

| 23 |

|

| 24 |

|

| 25 |

|

| 26 |

|

| 27 |

|

| 28 |

|

| 29 |

|

| 30 |

|

| 31 |

|

| 32 |

|

| 33 |

|

| 34 |

|

| 35 |

|

| 36 |

|

| 37 |

|

| 38 |

|

| 39 |

|

| 40 |

|

| 41 |

|

| 42 |

|

| 43 |

|

| 44 |

|

| 45 |

|

| 46 |

|

| 47 |

|

| 48 |

|

| 49 |

|

| 50 |

|

| 51 |

|

| 52 |

|

| 53 |

|

| 54 |

|

| 55 |

|

| 56 |

|

| 57 |

|

| 58 |

|

| 59 |

|

| 60 |

|

| 61 |

|

| 62 |

|

| 63 |

|

| 64 |

|

| 65 |

|

| 66 |

|

| 67 |

|

| 68 |

|

| 69 |

|

| 70 |

|

| 71 |

|

| 72 |

|

| 73 |

|

| 74 |

|

| 75 |

|

| 76 |

|

| 77 |

|

| 78 |

|

| 79 |

|

| 80 |

|

| 81 |

|

| 82 |

|

| 83 |

|

| 84 |

|

| 85 |

|

| 86 |

|

| 87 |

|

| 88 |

|

| 89 |

|

| 90 |

|

| 91 |

|

| 92 |

|

| 93 |

|

| 94 |

|

| 95 |

|

| 96 |

|

| 97 |

|

| 98 |

|

| 99 |

|

| 100 |

|

Former Entries | |

| X |

|

| X |

|

| X |

|

| X |

|

| X |

|

| X |

|

| X |

|

| X |

|

| X |

|

| X |

|

| X |

|

|

Browse Films by Title / Year / Reviews Nick-Davis.com Home / Blog / E-Mail | |

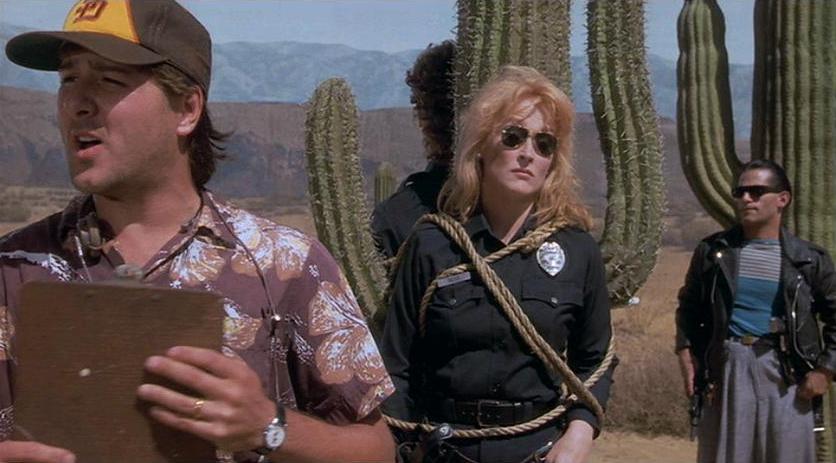

#54: Postcards from the Edge (USA, 1990; dir. Mike Nichols; cin. Michael Ballhaus; with Meryl Streep, Shirley MacLaine, Dennis Quaid, Gene Hackman,

Richard Dreyfuss, Robin Bartlett, Annette Bening, Rob Reiner, Mary Wickes, Dana Ivey, CCH Pounder)

(USA, 1990; dir. Mike Nichols; cin. Michael Ballhaus; with Meryl Streep, Shirley MacLaine, Dennis Quaid, Gene Hackman,

Richard Dreyfuss, Robin Bartlett, Annette Bening, Rob Reiner, Mary Wickes, Dana Ivey, CCH Pounder)IMDb For reasons I have specified above, Sandra Bernhard would have won my support for the Best Actress Oscar in 1990, even though Without You I'm Nothing is obviously not the sort of vehicle to which the Academy pays any mind—not only because they resist formal experiments, but because they don't even like to laugh. Unless, that is, the responsible party is someone like Meryl Streep, whose tragic-dramatic prestige conversely assures them that a little merriment never killed anyone. In Postcards from the Edge, Streep sufficiently tickled the voters' funny bones to at least score her a nod the year Bernhard should have won. Streep and Bernhard: few people's idea of a seamless pair, but they do share a knack for zeroing in on their targets, especially their punchlines, without hiding the mechanics of how they're doing it. Streep is a kind of performance artist: you watch the woman she's playing, and you simultaneously watch her play that woman. Sometimes, yes, this method can feel a bit clinical, especially when, as in Out of Africa or Dancing at Lughnasa, the tricksiness of her preferred style is out of proportion to the dullness of the character. At her best, though, Streep's "intellectual" quality is actually a conduit for a bountifully generous entertainer's impulse: both the character and its construction are invigorating spectacles, and for an audience to be gifted with both at once is like following a full and zesty meal with a rich and flavorful dessert. You can even eat them at the same time! You can go back and forth! Meryl's here to give give give. Take what pleases you. Enjoy it all. She, at least, is having a ball. Postcards from the Edge hails from that period in Streep's career when she suddenly and understandably appeared apprehensive about forever playing pietās and martyrs and wailing women from across the Earth's four corners. She had a Funny Period the same way Picasso had a Blue one, and though I haven't actually seen any of its other avatars (She-Devil, Defending Your Life, Death Becomes Her), her work in Postcards is so lively in detail that, again, you feel like you're getting several performances for the price of one. Meryl tokes up, she zones out, she trips, she sings twice, she shoots guns twice. But the real action is in the shifting sands of her face and her tiny symphonies of physical accents, whenever she's about the deceptively simple business of selling a line or a scene, or even a fellow actor's performance. Watch what a comic tour-de-force she finds just by crouching among a wire-rack of costumes on a movie-set, her eyes and her relative posture our only inlets into a twelve-tone coloratura of comic humiliation. Waking up, unexpectedly, in a rehab center, she parses out into multiple comic beats what many actors would fold or purée into a single affect: her dazedness, her breath, her shame, her fright, the blinding whiteness of the light and the room, the puzzling discovery of a plastic hospital bracelet around her arm, her dawning recognition that news of her predicament has certainly, already sprinted to undesired destinations. Carrie Fisher has filled her autobiographical script with choice one-liners and her trademark sensibility for observing life askance. "I have feelings for you," confesses a sun-kissed Dennis Quaid, to which Streep responds, "Well, how many? More than—two?", and while the line is a great gift to her (and there's way, way more where that came from), her muffled, almost foggy playing of it is a cadeau to Quaid, an earnest tryer who rarely knows, and certainly didn't know in 1990, how to anchor a scene or vary its rhythm. Streep forces him to shake things up, just like she keeps Shirley MacLaine's campy grandiloquence on a liberal but certain leash, letting her do her Thing, even getting her own zappy charge out of it, but also keeping everyone in service of the movie, especially of Fisher's voice. Like Streep, Fisher is possessed of a sophisticated hamminess that she isn't at all bashful about trotting out, so it's no surprise that the two women are such ample enthusiasts and protectors of each other. Fisher's overriding and self-analytical theme, that she has no idea who she is or who she should be, or whether those two concepts even remotely go together, also creates a winning ironic frame for Streep's own chameleonism: watching her change shape and mental fabric, even within seconds, weds the familiar pleasures to some new questions about exhibitionism and avoidance. Watching so many modern film comedies, I can't help wishing that they had been made fifty years ago; it's the single genre where the drop-off in quality strikes me as the most precipitous, largely because filmmakers' confidence in things like words, speed, and economy have shriveled to the size of a maraschino cherry. Postcards, though, is a rare example of a film that wouldn't be funny at any brisker pace, or with more rapid-fire actors. A more intricate style wouldn't add much—and besides, at zero cost, cinematographer Michael Ballhaus is already having fun moving Streep around the foregrounds, middle-grounds, and backgrounds of his shots, and she mines different kinds of comic gold depending on where she is: a miracle. Finally, in a major departure from most Hollywood comedies about Hollywood, Postcards feels credibly conditioned in what the industry actually is and how a set might actually feel: the anodyne hallways and lots and trailers, the dead intervals between camera set-ups, the way in which Streep's humbled B-lister keeps getting into personal fender-benders with producers, directors, wardrobe assistants, and crass starlets. Hollywood as a way of life, with its own cadences and its own soil, tillable for its very own jokes, is largely divorced from the clichés of celebrity and grotesque wealth. This Edge, then, is a terrifically accessible place, recognizable as a movie about parents and children, about Achilles heels, about the weeks and months of life that seem totally ceded to personal embarrassment, whether or not you have a drug problem, whether or not your mother is |

| Permalink | Favorites | Home | Blog |