|

Rank /

Title /

Year | |

| 1 |

|

| 2 |

|

| 3 |

|

| 4 |

|

| 5 |

|

| 6 |

|

| 7 |

|

| 8 |

|

| 9 |

|

| 10 |

|

| 11 |

|

| 12 |

|

| 13 |

|

| 14 |

|

| 15 |

|

| 16 |

|

| 17 |

|

| 18 |

|

| 19 |

|

| 20 |

|

| 21 |

|

| 22 |

|

| 23 |

|

| 24 |

|

| 25 |

|

| 26 |

|

| 27 |

|

| 28 |

|

| 29 |

|

| 30 |

|

| 31 |

|

| 32 |

|

| 33 |

|

| 34 |

|

| 35 |

|

| 36 |

|

| 37 |

|

| 38 |

|

| 39 |

|

| 40 |

|

| 41 |

|

| 42 |

|

| 43 |

|

| 44 |

|

| 45 |

|

| 46 |

|

| 47 |

|

| 48 |

|

| 49 |

|

| 50 |

|

| 51 |

|

| 52 |

|

| 53 |

|

| 54 |

|

| 55 |

|

| 56 |

|

| 57 |

|

| 58 |

|

| 59 |

|

| 60 |

|

| 61 |

|

| 62 |

|

| 63 |

|

| 64 |

|

| 65 |

|

| 66 |

|

| 67 |

|

| 68 |

|

| 69 |

|

| 70 |

|

| 71 |

|

| 72 |

|

| 73 |

|

| 74 |

|

| 75 |

|

| 76 |

|

| 77 |

|

| 78 |

|

| 79 |

|

| 80 |

|

| 81 |

|

| 82 |

|

| 83 |

|

| 84 |

|

| 85 |

|

| 86 |

|

| 87 |

|

| 88 |

|

| 89 |

|

| 90 |

|

| 91 |

|

| 92 |

|

| 93 |

|

| 94 |

|

| 95 |

|

| 96 |

|

| 97 |

|

| 98 |

|

| 99 |

|

| 100 |

|

Former Entries | |

| X |

|

| X |

|

| X |

|

| X |

|

| X |

|

| X |

|

| X |

|

| X |

|

| X |

|

| X |

|

| X |

|

|

Browse Films by Title / Year / Reviews Nick-Davis.com Home / Blog / E-Mail | |

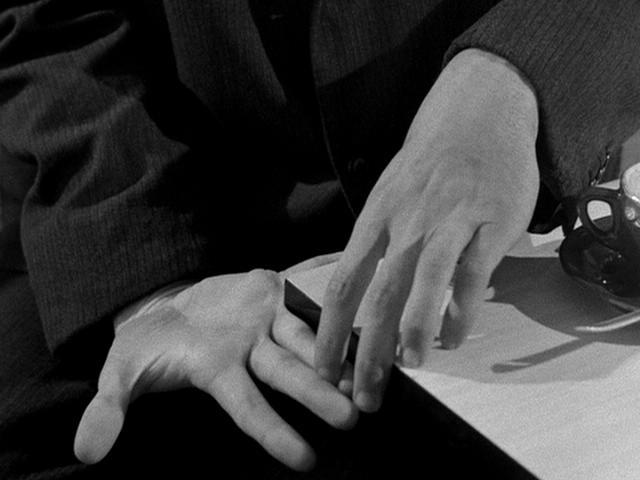

#68: Pickpocket (France, 1959; dir. Robert Bresson; cin. Léonce-Henri Burel; with Martin LaSalle, Marika Green, Jean Pélégri, Pierre Laymarie,

Kassagi, Dolly Scal, César Gattegno, Pierre Étaix)

(France, 1959; dir. Robert Bresson; cin. Léonce-Henri Burel; with Martin LaSalle, Marika Green, Jean Pélégri, Pierre Laymarie,

Kassagi, Dolly Scal, César Gattegno, Pierre Étaix)IMDb Nobody is born knowing anything, and often it matters when and where, and from whom or from what, you learn. I wouldn't normally embark with this platitude, in describing a film that keeps dodging platitudes even as it plays as a sort of sad Christian homily. But Pickpocket, which I first saw in college, was my introduction to the concept that a filmmaker could generate meaning from visual habits, from regulations of point of view—specifically, in this case, from the continual, isolated framings of hands as freestanding objects, as sensual artifacts, as criminal means, as emblems of hunger or expectation (the open palm), of aloofness or concealment (the hand behind the back, the fist in the pocket), of communion with others (the held hand, the caressing palm). Having had my heart won over to the cinema by Jane Campion's Piano, you'd think I would have thought more about hands and the grammars of the close-up, but The Piano was my overwhelming introduction to almost everything possible and medium-specific in the cinema, and the lure of impassioned, romantic, psychological narrative seemed to dictate or supercede almost everything else in the movie, save the music. Bresson and Pickpocket were temperamentally opposite, less oceanic, more teacherly. Though I'd never have guessed from Pickpocket that Bresson was regarded by many as an austere, even an ascetic filmmaker—the frissons of touch and of cunning and of mysterious couplings is thrilling, stiffly sexy, in Pickpocket—his film offered a stern epiphany to the bookworm so recently reborn as a film lover. You can start from the image. You can work outward from the hand, the brow, the closeup, the pocketbook, the clasp, the coat, the newspaper, the stairwell, the baseboard, the attic, the neighbor, the edit, the ellipsis, the music, and from there you can access the moral, the metaphysical, the cinematic. This is as true for the filmmaker as for the observer. You can film this way, or you can watch this way, though the experience is most remarkable when both of you are working in tandem. Pickpocket has a story, and offers itself easily to the story-seeking audience, but the story nonetheless bows before the visual, sonic, and rhythmic life of the film, rather than the other way around. These lessons, gorgeously and cryptically epigrammed in Bresson's short, famous book Notes on the Cinematographer, are by now so endemic to the way I think about movies that I often take them for granted. But watching Pickpocket, even spying it on my DVD shelf, nestled between Odds Against Tomorrow and Room at the Top (my discs are currently organized chronologically, then alphabetically within each year), is an instant reminder of how new this perspective on movies once was to me, and how new it was, too, to the 1959 audiences who trilled along giddily to the sexier, simultaneous innovations of Breathless, and who slipped right in to the new generation's humanism of the same year's 400 Blows, but who mostly didn't cotton to Pickpocket right away. To revisit the Criterion DVD is to recognize at once what an enigmatic and contradictory text this always was, and still remains. James Quandt recites on the commentary track the consensus line on the film's devout spirituality, while Gary Indiana rages in the liner notes about the fundamental "uselessness of Christian faith" in Pickpocket and in most Bresson, and about the palpable queerness of this putatively Catholic film. Paul Schrader introduces us to the movie as a sanctified object while two French journalists of the intelligentsia, smug with the air of having seen and "gotten" the movie, quiz the laconic Bresson about the odd and inhospitable qualities of what he has made, as though they doubt it will ever mean much to anyone. The Criterion packaging itself testifies to the film's august status, like a page of scripture, or a pietà, or a Tolstoy novella (one of which Bresson later filmed as L'Argent). But then Kassagi, the androgynous, Genetian, real-life thief from the movie pops up in French television footage, plying his "magic," bilking his audience, and demonstrating their hopeless gullibility—possibly ours as well. Bresson will later inherit a reputation for genius. Kassagi, meanwhile, will proceed to hang outside cinemas and inside cafés, nicking the purses and billfolds of absent-minded mandarins who see Bresson's movies and ponder their vaporous meanings. Pickpocket: a numinous essay on crime and also a how-to manual for criminals, a whispered reminder that while you're laudably thinking lofty thoughts, while you're laudably watching the world and its fascinations (like those distracted crowds at the two offscreen horse-races), someone is behind you, taking what's yours, poking at what you are, passing like a grey cloud. Pickpocket is a great crime movie, because it shows us vivid, unusual, and totally unglamorous things about crime. Its compulsiveness. Its choreography, as in those brilliant shots and scenes when Michel and Kassagi and the occasional accomplice keep wallets bobbing around like badminton birdies, or like Ophuls' earrings. Above all, its nervous, pilly loneliness. Guilt doesn't crash down on Michel like a stone ceiling or a penal code; the film doesn't scream or wail or exaggerate. Guilt swims through Michel like a rogue bubble in his blood. Whenever the camera moves unexpectedly, or Martin LaSalle's pupils dilate in their hard, stony way, or the lighting suddenly picks up the damp cracks in Michel's bedroom walls or the cheapness of his clothing, Pickpocket is genuinely unsettling. His restiveness spreads to us; sometimes we feel it more than he appears to. Maybe he just accepts it more fully than we do. The movie is brilliant at upsetting expectations, as in the arrhythmic, inscrutable courtship between Michel and true-hearted Jeanne, his mother's feline neighbor, or in the blink-and-you-miss-it two-year gap in the narrative continuity, or in the juxtaposition of Lully's sublime 17th-century music with this masterfully rendered but essentially grotty 20th-century parable. "I'll confess everything, but then I'll take it all back," says Michel from his jail cell at one pivotal moment, though Pickpocket's editing and the hiccups in its script have a way of making every moment feel pivotal. "I'll make it hard for them," he seethes, but not in a mustache-twirling way. You wouldn't find that in a Bresson film, even though Pickpocket does seem to give us a lot, as taut and plainspoken as prayer, and then it rescinds our first impressions, takes away our sense of comprehension, through a hundred tiny movements and flits of resonance. I loved Pickpocket on sight. I'm preoccupied with not wanting to make it sound "difficult," except in the way it gestates, growing difficult on reflection, multiplying its own possibilities, defying the succinctness of its 75 minutes. It drops you in a new, dazzling starting space: film can be anything. Film can leap off any object, with or without an orienting story, and can vault from there to the ethical, the philosophical, the beautiful, the corrupt. Pickpocket begins where few films ever arrive. But how do you know where you are? What do you make of it? That's up to you. |

| Permalink | Favorites | Home | Blog |