|

Rank /

Title /

Year | |

| 1 |

|

| 2 |

|

| 3 |

|

| 4 |

|

| 5 |

|

| 6 |

|

| 7 |

|

| 8 |

|

| 9 |

|

| 10 |

|

| 11 |

|

| 12 |

|

| 13 |

|

| 14 |

|

| 15 |

|

| 16 |

|

| 17 |

|

| 18 |

|

| 19 |

|

| 20 |

|

| 21 |

|

| 22 |

|

| 23 |

|

| 24 |

|

| 25 |

|

| 26 |

|

| 27 |

|

| 28 |

|

| 29 |

|

| 30 |

|

| 31 |

|

| 32 |

|

| 33 |

|

| 34 |

|

| 35 |

|

| 36 |

|

| 37 |

|

| 38 |

|

| 39 |

|

| 40 |

|

| 41 |

|

| 42 |

|

| 43 |

|

| 44 |

|

| 45 |

|

| 46 |

|

| 47 |

|

| 48 |

|

| 49 |

|

| 50 |

|

| 51 |

|

| 52 |

|

| 53 |

|

| 54 |

|

| 55 |

|

| 56 |

|

| 57 |

|

| 58 |

|

| 59 |

|

| 60 |

|

| 61 |

|

| 62 |

|

| 63 |

|

| 64 |

|

| 65 |

|

| 66 |

|

| 67 |

|

| 68 |

|

| 69 |

|

| 70 |

|

| 71 |

|

| 72 |

|

| 73 |

|

| 74 |

|

| 75 |

|

| 76 |

|

| 77 |

|

| 78 |

|

| 79 |

|

| 80 |

|

| 81 |

|

| 82 |

|

| 83 |

|

| 84 |

|

| 85 |

|

| 86 |

|

| 87 |

|

| 88 |

|

| 89 |

|

| 90 |

|

| 91 |

|

| 92 |

|

| 93 |

|

| 94 |

|

| 95 |

|

| 96 |

|

| 97 |

|

| 98 |

|

| 99 |

|

| 100 |

|

Former Entries | |

| X |

|

| X |

|

| X |

|

| X |

|

| X |

|

| X |

|

| X |

|

| X |

|

| X |

|

| X |

|

| X |

|

|

Browse Films by Title / Year / Reviews Nick-Davis.com Home / Blog / E-Mail | |

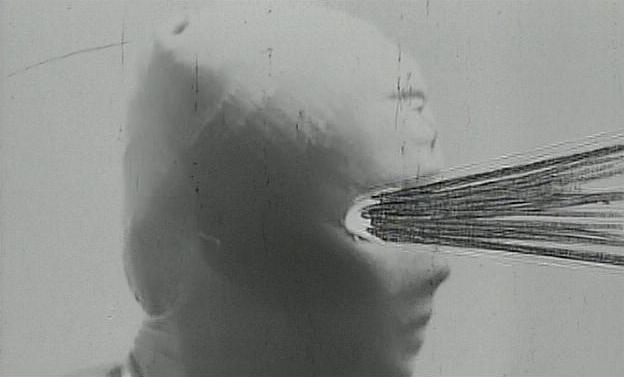

#41: Irma Vep (France, 1996; dir. Olivier Assayas; cin. Eric Gautier; with Maggie Cheung, Jean-Pierre Léaud,

Nathalie Richard, Nathalie Boutefeu, Bulle Ogier, Lou Castel, Alex Descas)

(France, 1996; dir. Olivier Assayas; cin. Eric Gautier; with Maggie Cheung, Jean-Pierre Léaud,

Nathalie Richard, Nathalie Boutefeu, Bulle Ogier, Lou Castel, Alex Descas)IMDb // My Page Olivier Assayas' Irma Vep crouches and teases from a funny, sexy, slinky space halfway between the chapbook and the manifesto. There is no doubt that Assayas, however offhanded his technique, means to shake up the French cinema. His characters can't stop bitching about the safe and stolid pictures that keep plodding around on Gallic screens, even as they join together to make a film of their own. Their shifty, shaky leader in this enterprise is René Vidal (Jean-Pierre Léaud), a once-fêted director about whom everyone now seems especially dubious. René has somehow succeeded in wheedling Maggie Cheung into flying halfway around the world to France in order to star in his remake of Les Vampires, Louis Feuillade's six-hour film serial of 1915-16. Unfortunately, René flummoxes himself and everyone else each time he tries to articulate why he is making this movie and what indeed he means for it to be. He has fiercely specific ideas about individual shots and scenes, and he forces his cast and crew through an intensely mannered, deliberately antiquarian project that none of them quite understands—and yet, when he watches the rushes at the end of a full day's work, he is apoplectic with disgust. More and more, Irma Vep insinuates that René isn't just a stern, eccentric taskmaster but a genuinely ill person. He vanishes from the set in the middle of the shoot, the victim of a rumored breakdown, at which point the studio recruits another director to steward the project. That's about it for story in Irma Vep, but what bewitches about the movie are its crafty, on-the-fly methods of capturing the stop-and-go rhythms of filmmaking, to such an extent that the nascent film-within-a-film is itself almost an afterthought, albeit a beguilingly odd one. Reviews routinely called Irma Vep a satire, but it's never perfectly clear that René's remake of Les Vampires is such a folly after all, and nor is it obvious that Assayas is exaggerating all that much the swirling tumult in and around a set. Ironically, the more heatedly René disavows his labor, the more the cameraman, costumer, and cast members devise their own excited inklings about the film's artistic potential. Then again, most of these characters are so quicksanded in their own private neuroses that it's a minor miracle that any film is coming together at all. Markus (Bernard Nissile), René's cinematographer of 15 years, is infuriated by the director's wordless dismissals of each day's work. The producers seethe with bureaucratic stresses and with petty suspicions of their colleagues. Laure (Nathalie Boutefeu), the second-billed actress, is diplomatically supportive of René's ambitions, at least until she learns that she'll inherit the lead role if the new director, José Mirano (Lou Castel), succeeds in appropriating the film. Most memorably, Zoé (Nathalie Richard), the perpetually frazzled and temperamental wardrobe supervisor, keeps trying to suture the flimsy latex of Maggie Cheung's principal costume—a zippered catsuit modeled less on Feuillade's original character than on Michelle Pfeiffer's Batman Returns get-up—while simultaneously nursing a potent but anxious crush on Maggie herself. While all of these characters repeatedly explode at each other, Maggie Cheung is almost supernaturally gracious and flexible: a refreshing detour from actress-as-diva clichés, not to mention an extremely able performance in the always difficult role of oneself. In a sense, Irma Vep takes shape as a series of challenges to Maggie's equanimity, but she keeps her cool not just around this retinue of barking headcases but in the face, too, of Eric Gautier's restive handheld camera. Then again, Maggie may be harboring her own secrets: in the one sequence where she separates from the group, she appears to sneak into a nearby hotel room and burgle an expensive necklace, while the naked owner gabs on her telephone mere steps away. Given its uncertain placement within Irma Vep's montage, Maggie may simply be dreaming this trespass, but something about the sheer, risky gratuitousness of her theft resonates with René's artistic vision and, indeed, with Assayas' own: all three artists play elaborate, improvisatory games with exotic objects. For both René and Assayas, Maggie herself is this object—and if anything, she understands René better as his psyche further unravels and his fetishistic fascination with her becomes more overt. "That's desire," she says, with kind, even-keeled understanding at the end of his confessional rant, "and I think it's okay, because that's what we make movies with." It's hard to write about Irma Vep and capture what is so special, playful, and exploratory about the movie. One major reason is that Assayas operates from such a jazzy visual sensibility that words are poor communicants for his signature fixations—for example, recurring shots of Maggie in her leather facemask, or the subtly sustained sequence shots in which Zoé's unrequited crush graduates from a subplot to a major assertion of the film. There's also the fact that, shaved of its last five minutes, Irma Vep would amount to a reasonably smart and enjoyably frisky sketch about art, recycling, and paranoia. Instead, Irma Vep unleashes a whopper of an open-ended finale: proof positive that you don't need a plot-twist, nor even much of a plot, to send your audience reeling out of the theater. As the crew of Les Vampires 2.0 gather to watch a rough assembly of footage by their hospitalized auteur, Assayas does more than call the bluff of René's skeptics. What he has crafted is so fearlessly, unspeakably strange that this modest, desultory movie suddenly quakes with the distilled force of aesthetic mystery. Forget Guy Maddin, or plastic bags blowing in the wind, or those blinding cityscapes at the ends of Happy Together and Adaptation. Though Assayas would reach further and score higher in demonlover (many of whose central motifs are already active here), Irma Vep bears the signature of a filmmaker who can stand far enough outside himself and his medium to see what is truly remarkable and also unsettling about both. He concocts, via a story about resurrecting old images, a tantalizing foretaste of the weird, hypnotic, possible futures of movies. |

| Permalink | Favorites | Home | Blog |