Cannes Festivals by Year:

Prizes, Juries, Favorites

Other Fests: Venice / Chicago

Stay tuned for more yearly indexes!

Browse Films by

Title /

Year /

Reviews

Nick's Flick Picks

Home /

Blog /

E-Mail

|

|

Cannes 1995: Jury Roundtable #2 / Click Here to Comment

Picking up where we left off, this roundtable covers the movies programmed at Cannes, especially in the Main Competition, on Day 6, Day 7, and Day 8...

NICK: In our last episode we observed that, for better or worse, several of the Competition titles that kicked off Cannes '95 adhered to styles you'd probably call "modest" if you called them anything. You couldn't say that about the mid-festival titles; indeed, some commentators asserted quite the opposite. Harlan Kennedy, amid his admiring but highly qualified appraisal of The Neon Bible for Film Comment, ventured that "Davies's film epitomized a trend at Cannes: the tendency for strong style-signatures to attach themselves to fallible documents." Among our group, I'm guessing that many folks might agree with that statement regarding several of these movies: not just The Neon Bible but Hou's Good Men, Good Women, Clark's Kids, Loach's Land and Freedom, Martone's Nasty Love, Zhang's Shanghai Triad (which some early odds-makers had tapped as a Palme favorite), and Angelopoulos's Ulysses' Gaze (which, to the director's notorious consternation, "only" won the Grand Jury Prize for second-best film of the fest). But I'm equally suspicious that we'll have divided opinions about which films marry style and material most successfully, even if that marriage is one of purposeful and fruitful discordance. And nobody will be shocked if we have highly divided opinions about which of these documents were most "fallible." In highly eclectic ways, these movies make it their business to be polarizing. NICK: In our last episode we observed that, for better or worse, several of the Competition titles that kicked off Cannes '95 adhered to styles you'd probably call "modest" if you called them anything. You couldn't say that about the mid-festival titles; indeed, some commentators asserted quite the opposite. Harlan Kennedy, amid his admiring but highly qualified appraisal of The Neon Bible for Film Comment, ventured that "Davies's film epitomized a trend at Cannes: the tendency for strong style-signatures to attach themselves to fallible documents." Among our group, I'm guessing that many folks might agree with that statement regarding several of these movies: not just The Neon Bible but Hou's Good Men, Good Women, Clark's Kids, Loach's Land and Freedom, Martone's Nasty Love, Zhang's Shanghai Triad (which some early odds-makers had tapped as a Palme favorite), and Angelopoulos's Ulysses' Gaze (which, to the director's notorious consternation, "only" won the Grand Jury Prize for second-best film of the fest). But I'm equally suspicious that we'll have divided opinions about which films marry style and material most successfully, even if that marriage is one of purposeful and fruitful discordance. And nobody will be shocked if we have highly divided opinions about which of these documents were most "fallible." In highly eclectic ways, these movies make it their business to be polarizing.

Speaking for myself, I liked all of them except one, albeit to varying degrees. I'm stunned at which film I wound up liking best, but it's my party and I can be coy as long as I want to. Show me your biggest hits and misses and I'll show you mine.

ALEX HEENEY: Because I was splitting my time between Cannes 2015 prep and the Cannes 1995 films, I've only seen Land and Freedom, Kids, and The Neon Bible. I did try to watch Good Men, Good Women, and I made it through the first 10 minutes twice, but I fell asleep at that point both times and then gave up. It is very possible that Hou will get a Palme this year for The Assassin, given the amount of warm praise it got from my colleagues in the press. I hope not, though, because it's mostly people sitting still in rooms making profound faces, yet it still manages to be confusing. (Ed: Alex got her wish!)

Anyway, I'm getting sidetracked. My favourite of the bunch is by far Land and Freedom. I'm especially taken with the level of detail by which it explains the politics of what's going on and the detrimental in-fighting between each of the separate groups against the fascists. If you'd walked into the film knowing very little about the Spanish Civil War, you'd walk out with an impressively good portrait of what went wrong, including how good intentions got co-opted by powerful external forces with a separate agenda. Although the protagonist's journey is the familiar loss-of-innocence story, it felt so justified by his intellectual and emotional engagement, and by the mistakes he made; his arc seemed organic rather than manufactured movie magic. The film also manages to transcend the subject matter, because of how specifically the political machinations and issues are laid out. This isn't the only war or battle where allies became enemies, slowing progress, if not outright causing failure. Anyway, I'm getting sidetracked. My favourite of the bunch is by far Land and Freedom. I'm especially taken with the level of detail by which it explains the politics of what's going on and the detrimental in-fighting between each of the separate groups against the fascists. If you'd walked into the film knowing very little about the Spanish Civil War, you'd walk out with an impressively good portrait of what went wrong, including how good intentions got co-opted by powerful external forces with a separate agenda. Although the protagonist's journey is the familiar loss-of-innocence story, it felt so justified by his intellectual and emotional engagement, and by the mistakes he made; his arc seemed organic rather than manufactured movie magic. The film also manages to transcend the subject matter, because of how specifically the political machinations and issues are laid out. This isn't the only war or battle where allies became enemies, slowing progress, if not outright causing failure.

IVAN ALBERTSON: Ken Loach will never be mistaken for a great visual stylist, but his straightforward approach is perfect for bringing forth the political complexity of Land and Freedom. It's admittedly grounded in Jim Allen's formidably lean screenplay, which never pauses for David to declare his communist ideals or justify enlisting to his girl back home (indeed, she's only the recipient of letters), but Loach also exhibits a keen sense of proportion. One can easily imagine the Spanish Civil War made bombastic in other hands, or even in Loach's own, but he's more interested in the nuts and bolts of guerrilla strategy and the difficulty of achieving progress, or even agreeing on what progress is. The scenes of in-fighting have a marvelous verisimilitude that recall Wiseman more than any fiction film. I really liked how the battles are small and impromptu with little immediate gain and the potential for enormous loss. For me, Land and Freedom achieves a happy medium between Sharaku and Beyond Rangoon: the narrative is anchored by its protagonist without artificially revolving around him. It's one man's near-forgotten story that also evokes the fate of hundreds of thousands.

ALEX: Certainly Loach doesn't attain the same kind of stylized filmmaking as, say, Hou, but I did find that the aesthetic choices were appropriate and thoughtful. When David first gets to the battlefield, so much of the imagery is of lush green fields and camaraderie, his idealism still intact. But when he gets injured and finds himself in the city, there's a great sense of suspense and terror, when we first hear the soldiers banging on doors, and then see David watching it all unfold. What were previously theoretical, second-hand cautionary tales suddenly become real. The camera is always so in line with David's perspective that we get jaded and lose our idealism about the fight just as he does. At the beginning, Loach's decision not to shoot the civilians is sympathetic, if a bit worrisome to anyone who has seen a war film. By the end, we're more cynical, more willing to accept the sacrifice David didn't initially want to make.

IVAN: I understand why Beyond Rangoon and Jefferson in Paris screened early in the festival, for they would have appeared even more deficient had they been unveiled after Land and Freedom (but as you say, Nick, why include them at all?). In contrast, The Neon Bible can't help but seem wan by comparison to Terence Davies's exquisite prior work. It looks, sounds, and feels like a Davies film, but something vital is missing. I don't think it's simply the foreknowledge that this isn't his own memoir. I went in confident in his ability to turn another's prose into indelible memories, but it comes off rather sparsely imagined. While it's hardly full of incident, what little there is is too tangible to lend well to his fragmented style, which this time consists of as many broad strokes as enticing ellipses. David is ultimately less of a passive spectator than the typical Davies lad, but his behavior plays less like a gradual coming-of-age than a sudden lashing out. I suspect that Toole's novel is too pointed a social critique to survive an impressionistic treatment. IVAN: I understand why Beyond Rangoon and Jefferson in Paris screened early in the festival, for they would have appeared even more deficient had they been unveiled after Land and Freedom (but as you say, Nick, why include them at all?). In contrast, The Neon Bible can't help but seem wan by comparison to Terence Davies's exquisite prior work. It looks, sounds, and feels like a Davies film, but something vital is missing. I don't think it's simply the foreknowledge that this isn't his own memoir. I went in confident in his ability to turn another's prose into indelible memories, but it comes off rather sparsely imagined. While it's hardly full of incident, what little there is is too tangible to lend well to his fragmented style, which this time consists of as many broad strokes as enticing ellipses. David is ultimately less of a passive spectator than the typical Davies lad, but his behavior plays less like a gradual coming-of-age than a sudden lashing out. I suspect that Toole's novel is too pointed a social critique to survive an impressionistic treatment.

TIM BRAYTON: Ivan, I've spent more time thinking about why The Neon Bible felt so empty and unfulfilling than I've thought about any aspect of any of these films, and I can't come up with anything better than you've got. There's an artificial feeling to the sets and performances that's not so very different from Davies's earlier films, but this time around it was so hollow and disinterested in its characters that none of them felt like more than concepts to be scribbled in later. (And I'm simply going to co-sign all of your thoughts on Land and Freedom, while adding a solitary note of grousing: that "granddaughter reading his letters" present-day frame narrative was simply inelegant).

ALEX: I wanted very much to like The Neon Bible, as a card-carrying Toole, Davis, and Rowlands fan. I loved the artificiality of it, the way the house is clearly a set, and so much of the action is framed in windows, as if it's happening on a stage (or, more literally, a window into the past). It's a neat way of thinking about memory, a facsimile of the real thing. But I also found it emotionally empty, with plot threads opened but not explored. The boy keeps getting referred to as a "sissy" by his father, but is this plain misogynistic talk or is his sexuality keeping him from fitting in? Why is the boy so isolated from his peers and drawn to his aunt? None of this is really fully explored, as we focus more on why Rowlands's character is mesmerizing—without getting too deep, though, into her character's psychology, or whatever personal issues landed her in the story in the first place.

TIM: I feel like the phrase "strong style-signatures to attach themselves to fallible documents" is common to enough movies that you could apply it to any collection of 24 films and assume you've described at least a handful of them, but it's a particularly appropriate slight against The Neon Bible. I'd also happily apply it to The City of Lost Children, which we all hashed out last time, and to Shanghai Triad, which is so enormously a Zhang Yimou film in the way it uses color and Gong Li's face, and which, thanks to cinematographer Lu Yue, is so insensibly beautiful. Shanghai is the straight-up prettiest film we've run across yet, which isn't the same as saying that it's the best shot, but I'll take it anytime over the drab Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea or the fine but pedestrian-looking Carrington. Still, there's just not that much interesting or insightful in Shanghai's characterizations or story. It's not quite as airless and divorced from its humans as The Neon Bible, but it doesn't do much to argue that we need to care about them as more than vessels for a lively re-enactment of 1930s Shanghai—at least not until it makes a break for gangster melodrama in the last thirty minutes. TIM: I feel like the phrase "strong style-signatures to attach themselves to fallible documents" is common to enough movies that you could apply it to any collection of 24 films and assume you've described at least a handful of them, but it's a particularly appropriate slight against The Neon Bible. I'd also happily apply it to The City of Lost Children, which we all hashed out last time, and to Shanghai Triad, which is so enormously a Zhang Yimou film in the way it uses color and Gong Li's face, and which, thanks to cinematographer Lu Yue, is so insensibly beautiful. Shanghai is the straight-up prettiest film we've run across yet, which isn't the same as saying that it's the best shot, but I'll take it anytime over the drab Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea or the fine but pedestrian-looking Carrington. Still, there's just not that much interesting or insightful in Shanghai's characterizations or story. It's not quite as airless and divorced from its humans as The Neon Bible, but it doesn't do much to argue that we need to care about them as more than vessels for a lively re-enactment of 1930s Shanghai—at least not until it makes a break for gangster melodrama in the last thirty minutes.

But anyway, Nick invited us to pick our best and worst from this batch, and those choices couldn't be more clear-cut for me. Ironically my least favorite and favorite films here are possibly the two most similar projects: both are stories of the way young people in an urban setting interact with each other and the spaces around them, filmed by cameras that silently stand back and allow action to unfold as it wants to. The difference is that Good Men, Good Women (which I suspect exactly typifies the "fallible documents" trend to at least some of the people in this conversation) is so conscious of how its seemingly inflectionless camera captures human movement. Hou Hsiao-Hsien's grasp of the way that lighting and visual pacing can guide our feelings towards the characters gives it nuance, belying how outwardly plain the film pretends that its style is. I get that its attempt to marry a present-day story with the life of a 1940s political radical is pretty much a non-starter, but each individual element of the film works so terrifically for me—expressing how the characters think and feel without broadcasting it through narrative—that I'm willing to overlook the seams.

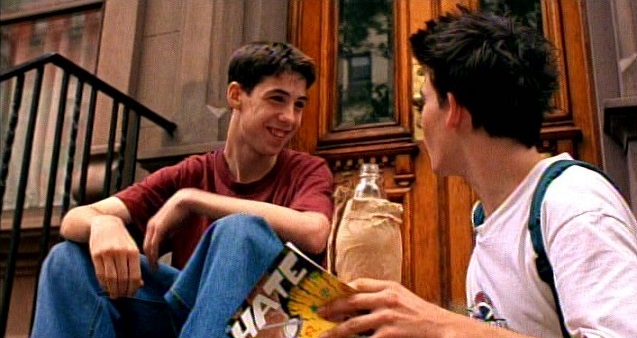

Whereas Larry Clark's Kids strikes me as artless provocation, a movie that I find too ugly visually to deal with on any deeper level. There's a slapdash attempt at "realism" that feels uncaring and sloppy to me, and that doesn't help the nastiness of the movie go down any easier, especially since that nastiness is so random. The much-publicized fact of 19-year-old Harmony Korine writing about the people and places he knew and the edgy behaviors in which he engaged would seem to suggest this is meant to be a naturalistic look at the way life happens without the burnishments of Hollywood. But both the writing and directing slip much too easily into "PARENTS, DO YOU KNOW WHAT YOUR CHILDREN ARE DOING!?" sensationalism to take any of it at all seriously. It managed to repel me on every level more than Beyond Rangoon did. No easy feat.

IVAN: Oh good, we have disagreement! I'd been waiting for the rundown of What's Wrong With 'Kids'? these past few days before I presented my defense, and now it has arrived in full force. It seems our differences stem from the value each of us places on realism, as well as the different calibrations of our real-o-meters. Our eyes may even be differently calibrated: I find the grainy, saturated images gorgeous. The naturalism of Kids is hard to praise without in effect arguing "This Is The Way It Is" (cue Janet Maslin), but for me the appeal is more micro: the fully-embodied characters, the way they relate, the dynamic environment. This is hard to pull off; it's not simply the default mode for those lacking inspiration. While the dialogue at times seems designed to stand in for an entire generation ("This is what boys think of girls, and this is how girls actually are"), the actors make it vibrant and personal. It helps enormously that Clark sincerely identifies with his characters. While a 52-year-old man's fixation on adolescent sex may be problematic to some, his lack of distance keeps it from being the scold many claim it is. He sees himself as one of them, and it goes a long way toward normalizing Korine's blatant provocations. Unfortunately, the HIV-positive test casts a pall over the film, turning it into a cheap race against the cock. It's a real shame, because otherwise the hangout vibe is closer to something like Dazed and Confused. I can see finding the behavior too repellent to warrant such an easygoing tone, but I like the way I feel entrenched in the group's moral rot. When they impulsively beat up the man in the park, only one person disapproves, weakly and after the fact, and nothing more is made of it. I much prefer this immediacy to preaching from on high. Tim, what would your ideal version of Kids look like, if "non-existent" is not an option? IVAN: Oh good, we have disagreement! I'd been waiting for the rundown of What's Wrong With 'Kids'? these past few days before I presented my defense, and now it has arrived in full force. It seems our differences stem from the value each of us places on realism, as well as the different calibrations of our real-o-meters. Our eyes may even be differently calibrated: I find the grainy, saturated images gorgeous. The naturalism of Kids is hard to praise without in effect arguing "This Is The Way It Is" (cue Janet Maslin), but for me the appeal is more micro: the fully-embodied characters, the way they relate, the dynamic environment. This is hard to pull off; it's not simply the default mode for those lacking inspiration. While the dialogue at times seems designed to stand in for an entire generation ("This is what boys think of girls, and this is how girls actually are"), the actors make it vibrant and personal. It helps enormously that Clark sincerely identifies with his characters. While a 52-year-old man's fixation on adolescent sex may be problematic to some, his lack of distance keeps it from being the scold many claim it is. He sees himself as one of them, and it goes a long way toward normalizing Korine's blatant provocations. Unfortunately, the HIV-positive test casts a pall over the film, turning it into a cheap race against the cock. It's a real shame, because otherwise the hangout vibe is closer to something like Dazed and Confused. I can see finding the behavior too repellent to warrant such an easygoing tone, but I like the way I feel entrenched in the group's moral rot. When they impulsively beat up the man in the park, only one person disapproves, weakly and after the fact, and nothing more is made of it. I much prefer this immediacy to preaching from on high. Tim, what would your ideal version of Kids look like, if "non-existent" is not an option?

It's interesting how we disagree about which aesthetic is best for revealing character. It's not necessarily a problem that Good Men, Good Women, like most Hou, operates at a physical and emotional distance from its characters. Rather, the incessant banality is what makes my eyes glaze over. Interiority isn't just obscured; it doesn't seem to exist at all. I don't feel that the emphasis on light and decor, however skillful, works toward creating a living history or enhancing the human drama. It only underscores the void.

At least Good Men, Good Women succeeds in capturing the quotidian, which makes it vastly more tolerable than the stultifying portentousness of Ulysses' Gaze. There's nary a moment in its three hours that rings true—I'll grant it the sequence where several years pass in a single take—and countless that ring incredibly false. Sure, it's interested in being "a poetic meditation on history and memory," but it feels leaden ("You're sailing in dark waters now...") and expository ("Those are the Albanian illegal immigrants!"). I would sooner give Best Actress to "Young Prostitute" from Between the Devil... than anything to this monotonous dirge. Can you feel the suffering? At least Good Men, Good Women succeeds in capturing the quotidian, which makes it vastly more tolerable than the stultifying portentousness of Ulysses' Gaze. There's nary a moment in its three hours that rings true—I'll grant it the sequence where several years pass in a single take—and countless that ring incredibly false. Sure, it's interested in being "a poetic meditation on history and memory," but it feels leaden ("You're sailing in dark waters now...") and expository ("Those are the Albanian illegal immigrants!"). I would sooner give Best Actress to "Young Prostitute" from Between the Devil... than anything to this monotonous dirge. Can you feel the suffering?

TIM: Honestly, you've already identified the single change I'd make to Kids that would most make it palatable to me: cutting out the ticking-time bomb scenario in the second half, from which a huge amount of the prurience I see in the movie derives. (I have no hope whatsoever of improving on "race against the cock", so I'm not even going to try.) Of course, this movie needs to talk about HIV, and it probably needs to do that specifically through an unrepentant character like Telly. But the melodramatic angle is a huge turn-off to me, and it's the single biggest reason I see this as a puritanical, paranoid screed. I also don't think Clark uses the camera as anything but a recording device. I long for the movie to have the same kind of "this looks casual and natural but we're actually doing a whole lot to situate your attitude towards the characters" cinematography that happens in the equally squalid, equally youth-oriented films of the Dardennes. And it shocks me to realise that, here in 1995, none of us have actually seen anything by the Dardennes, since La promesse won't come out yet for over a year. So I might just be longing for an anachronistic flavor of realism.

That all being said, I'm less excited about our disagreements than our agreement: I was so worried that I'd be the only person to be bored stiff by Ulysses' Gaze and it would make me feel like a philistine. There are plenty of individual scenes that work—in isolation, the dismantled Lenin statue drifting down the river is an absolute corker of an image—but the whole thing is self-important to the point of parody. I've loved Angelopoulos elsewhere, but this one is just too damn smug and glacially paced.

AMIR SOLTANI: Good Men, Good Women is my favourite of the Competition bunch, a surefire candidate for the Palme, which Hou might finally win twenty years later. I agree with Tim that the (three?) parts aren't exactly seamless, and I think if Hou had not attempted to suture them together—or even collected them as three parts offered chronologically—the end result would have been more coherent. But I'm not sure that's the sensory response the film wants from us. I was mesmerized by every frame, connecting with them individually and detached from the narrative as a whole. I wonder if the order of the expositions is of any importance here at all. The raw energy of the scene wherein the protagonist cries into the silent phone, or the mystifying curiosity of the fight on the badminton court seem completely self-contained, unburdened by narrative demands. Admittedly, this structure works because Hou's visual sensibility can make these separate moments so effective. As Tim put it before me, "He has a grasp of the way lighting and visual pacing can guide our feeling toward the characters." AMIR SOLTANI: Good Men, Good Women is my favourite of the Competition bunch, a surefire candidate for the Palme, which Hou might finally win twenty years later. I agree with Tim that the (three?) parts aren't exactly seamless, and I think if Hou had not attempted to suture them together—or even collected them as three parts offered chronologically—the end result would have been more coherent. But I'm not sure that's the sensory response the film wants from us. I was mesmerized by every frame, connecting with them individually and detached from the narrative as a whole. I wonder if the order of the expositions is of any importance here at all. The raw energy of the scene wherein the protagonist cries into the silent phone, or the mystifying curiosity of the fight on the badminton court seem completely self-contained, unburdened by narrative demands. Admittedly, this structure works because Hou's visual sensibility can make these separate moments so effective. As Tim put it before me, "He has a grasp of the way lighting and visual pacing can guide our feeling toward the characters."

As for my least favourite, well... I don't tend to write a lot about flat-out stinkers, mostly because I find no joy in tearing films down, but Kids deserves as much negativity as I can muster. Realism is often a trap; and it's dubious to call a film like Kids an attempt at realism when it utterly fails to transcend the real-life trappings of its subject. In other words, familiarity doesn't necessarily translate to insight. While it isn't unreasonable to argue that filmmakers who know their characters and milieu on a personal level offer a deeper, more sensitive approach, that certainly isn't the case with Korine. It isn't enough to have been a teenager in and around that time in America to write smartly about teenagers in and around that time in America. Does the artist not have to be one step ahead of his characters—let alone his audience—to study them carefully? And this impression of immaturity isn't simply generated by the one-dimensional callowness of the characters themselves. One can paint portraits of vapid teenagers that are nonetheless compelling and complex; see Sofia Coppola's The Bling Ring. The problem here is that Korine and, worse yet, the 52-year-old Clark give the impression that, had they been present in the environment of the film amongst that group of kids, they would have had nothing more meaningful to contribute other than "Bro, that pussy yo! Yea, bro!"

NICK: I'm halfway between Tim and Ivan on Kids. I agree Clark identifies with his characters, instead of filming them from atop some moral pedestal. Still, that beating at the skate park doesn't seem any better-served by the film's noncommittal impassivity than it would by shrill moral hectoring. There's no way to feel about that incident except against it, so we don't need any glossing, but the sequence speaks to Clark's Crash-like desire to adduce as many instances of waywardness and turpitude as he can. I frankly don't buy the scene as more than another horrible notch in that belt with which Kids keeps beating us. That repeated urge to Put Us Through Something seemed more falsely structuring of the film than Jennie's quest to find Telly. I admired Kids more during less hyperbolically awful interludes, at no cost to their unnerving power: for example, Ruby's blend of nonchalance, fear, and something close to arrogance in the AIDS clinic; or the nightswimming scene in which every participant flirts with the edge of some drastically nonconsensual act, but none summons the will either to commit or forestall a crime. All of them seem suddenly uncertain of the "roles" they're about to cast themselves in. That felt plausible to me in ways other scenes didn't, and more in keeping with the visual style: realist, but also an amped-up facsimile of realism. I didn't leave the film fuming, but I'll take Korine's Gummo or Clark's Ken Park any day over even the most successful passages of Kids, and I saw nothing to merit its Competition spot or its pungent air of being so impressed with itself. NICK: I'm halfway between Tim and Ivan on Kids. I agree Clark identifies with his characters, instead of filming them from atop some moral pedestal. Still, that beating at the skate park doesn't seem any better-served by the film's noncommittal impassivity than it would by shrill moral hectoring. There's no way to feel about that incident except against it, so we don't need any glossing, but the sequence speaks to Clark's Crash-like desire to adduce as many instances of waywardness and turpitude as he can. I frankly don't buy the scene as more than another horrible notch in that belt with which Kids keeps beating us. That repeated urge to Put Us Through Something seemed more falsely structuring of the film than Jennie's quest to find Telly. I admired Kids more during less hyperbolically awful interludes, at no cost to their unnerving power: for example, Ruby's blend of nonchalance, fear, and something close to arrogance in the AIDS clinic; or the nightswimming scene in which every participant flirts with the edge of some drastically nonconsensual act, but none summons the will either to commit or forestall a crime. All of them seem suddenly uncertain of the "roles" they're about to cast themselves in. That felt plausible to me in ways other scenes didn't, and more in keeping with the visual style: realist, but also an amped-up facsimile of realism. I didn't leave the film fuming, but I'll take Korine's Gummo or Clark's Ken Park any day over even the most successful passages of Kids, and I saw nothing to merit its Competition spot or its pungent air of being so impressed with itself.

ALEX: Kids is also, easily, my least favourite from this set. It really ought to be titled Boys, considering how little it's invested in the perspective of its female characters. Aside from that one scene of the girls talking trash together, we're almost entirely in the heads, lives, and perspectives of the boys. Chloë Sevigny's is the only female character with a consistent through-line, and her purpose is to be the cautionary tale for Tully's horrible actions. Aside from anger and fear, she doesn't get to play much, let alone have a plot beyond finding Tully to tell him he's HIV positive.

I'm also not sure I entirely buy that these girls would all be seduced by Tully so easily. That's partly because we don't have to deal with the aftermath. He deflowers a twelve-year-old, and then she drops out of the movie just as quickly as Tully drops her. Did she enjoy it? Is she going to go brag to her friends, only to later find out the terrible news? We get none of her perspective. Pretty much, the film's message seems to be that the boys are morality-free horndogs, and the girls are happy to stew in the gutter with them, at least for a while. Otherwise, they're victims. My main takeaway about the film's aesthetic is that it's hideous to look at, which I can see as being the point: this is a grotesque world. I can't say I was wowed by the film's aesthetic aiming for realism, but I also don't fault it for being aimless.

NICK: All right, Kids, go huff in the corner while we get back to the movies you keep trying to shove out the way. Proving I'll never be one of the cool kids anyway, I have to admit I liked Ulysses' Gaze. If your style is as singular as Theo Angelopoulos's (or, as it happens, Terence Davies's), I'll forgive a lot, even if your gameplan stays pretty familiar. Indeed, the limitations in these filmmakers' aesthetics often served the material for me in unexpected ways, or at least showed something new in it. Maybe "unexpected" is a reach for Ulysses, which proceeds along a route you can forecast, narratively and rhetorically. Angelopoulos has indeed made huge swaths of this movie before, with actors better-synced to his vision and with fuller warrants for his grandiose conceptions. But sometimes my love for a filmmaker is a sheer matter of proportion, if not outright mathematics: I dig the radius Angelopoulos's camera describes from the centers of his frames, standing further away from them than most filmmakers would, and using his phenomenal gifts for pacing and choreographing camera movements to draw us into character, incident, or mood without exactly penetrating or clarifying them. History feels heavy; episodes feel less like dramatic beats than tectonic plates. (I could say all the same things, admiringly, about Good Men, Good Women, which I liked even more than Ulysses' Gaze, and I don't always like Hou.) I liked the long game Ulysses was playing even when yet another Maïa Morgenstern avatar showed up (IIII geeeett iiitt..), or Harvey Keitel chewed out his umpteenth, unwieldy proclamation about Time or Film. Angelopoulos can film a bombed-out city, a desolate plain, and (as Tim says) a barge moving down a river like almost nobody else, stamping out signs of life from these scenes but somehow infusing them with historical dynamism. I can't get too mad at him, though the Grand Jury Prize is manifestly generous, as if honoring the film's nutritional content more than its insight or finesse—two areas where this film adequately sated me, though possibly only me? NICK: All right, Kids, go huff in the corner while we get back to the movies you keep trying to shove out the way. Proving I'll never be one of the cool kids anyway, I have to admit I liked Ulysses' Gaze. If your style is as singular as Theo Angelopoulos's (or, as it happens, Terence Davies's), I'll forgive a lot, even if your gameplan stays pretty familiar. Indeed, the limitations in these filmmakers' aesthetics often served the material for me in unexpected ways, or at least showed something new in it. Maybe "unexpected" is a reach for Ulysses, which proceeds along a route you can forecast, narratively and rhetorically. Angelopoulos has indeed made huge swaths of this movie before, with actors better-synced to his vision and with fuller warrants for his grandiose conceptions. But sometimes my love for a filmmaker is a sheer matter of proportion, if not outright mathematics: I dig the radius Angelopoulos's camera describes from the centers of his frames, standing further away from them than most filmmakers would, and using his phenomenal gifts for pacing and choreographing camera movements to draw us into character, incident, or mood without exactly penetrating or clarifying them. History feels heavy; episodes feel less like dramatic beats than tectonic plates. (I could say all the same things, admiringly, about Good Men, Good Women, which I liked even more than Ulysses' Gaze, and I don't always like Hou.) I liked the long game Ulysses was playing even when yet another Maïa Morgenstern avatar showed up (IIII geeeett iiitt..), or Harvey Keitel chewed out his umpteenth, unwieldy proclamation about Time or Film. Angelopoulos can film a bombed-out city, a desolate plain, and (as Tim says) a barge moving down a river like almost nobody else, stamping out signs of life from these scenes but somehow infusing them with historical dynamism. I can't get too mad at him, though the Grand Jury Prize is manifestly generous, as if honoring the film's nutritional content more than its insight or finesse—two areas where this film adequately sated me, though possibly only me?

If I were deciding, that Grand Jury Prize would have gone straight to Nasty Love, one of the least heralded movies in the whole lineup, and perhaps the least likely to be charged with pretense. Imagine Volver's characters recast into one of Almodóvar's fiercer contraptions, like Live Flesh or Bad Education, but with a distinctly Italian mix of psychological ferocity and sensual gusto. Anna Bonaiuto stars as Delia, a middle-aged woman who still lives alone, embarrassed at her aging mother's solicitude and pity, often conveyed through drop-in visits (and she doesn't even live in the same city!). Imagine Delia's surprise when mommie dearest calls her in the throes of some sexual escapade with a stranger, hangs up mid-guffaw, and turns up dead in the surf shortly after. The rest of the film unfolds as a detective story in which Delia—entirely flabbergasted in some respects, quick to draw conclusions in others—tries to decode what happened. That pursuit means picking at some scabs related to her own history, sexuality, and personality. The story moves like a Ruth Rendell mystery. Mario Martone directs it with color and flair that never mitigate the lean, mean mechanics of plot or the grottiness at its heart. I watched this one with Ivan and Tim, so I know they basically liked it, but am I crazy for classifying this as, so far, the best of the fest? If I were deciding, that Grand Jury Prize would have gone straight to Nasty Love, one of the least heralded movies in the whole lineup, and perhaps the least likely to be charged with pretense. Imagine Volver's characters recast into one of Almodóvar's fiercer contraptions, like Live Flesh or Bad Education, but with a distinctly Italian mix of psychological ferocity and sensual gusto. Anna Bonaiuto stars as Delia, a middle-aged woman who still lives alone, embarrassed at her aging mother's solicitude and pity, often conveyed through drop-in visits (and she doesn't even live in the same city!). Imagine Delia's surprise when mommie dearest calls her in the throes of some sexual escapade with a stranger, hangs up mid-guffaw, and turns up dead in the surf shortly after. The rest of the film unfolds as a detective story in which Delia—entirely flabbergasted in some respects, quick to draw conclusions in others—tries to decode what happened. That pursuit means picking at some scabs related to her own history, sexuality, and personality. The story moves like a Ruth Rendell mystery. Mario Martone directs it with color and flair that never mitigate the lean, mean mechanics of plot or the grottiness at its heart. I watched this one with Ivan and Tim, so I know they basically liked it, but am I crazy for classifying this as, so far, the best of the fest?

ALEX: I'm tempted to skip Ulysses' Gaze after reading your thoughts, Ivan. But I'm now very intrigued by Nasty Love, which I could only find in PAL format with French subtitles. Luckily, I've spent the last week reading French subtitles (tall people at Cannes block the English ones!) so it shouldn't be too much of a stretch.

TIM: I feel like I've already talked enough, but I will pop in to confirm: Nick, you are not crazy. If it wasn't for the Hou, Nasty Love would be my favorite film so far, and I'll throw in that Bonaiuto is on my Best Actress shortlist.

AMIR: I also agree with you that Nasty Love was a pleasant surprise, and not just for Bonaiuto's steely performance. Similar to Sharaku, though not quite to the same extent, I knew I was missing the sociocultural nuances of Italian culture and inter-city relationships and politics. But even on a purely technical level, this is an impressive accomplishment—that sequence in the bathhouse is as good as any single scene we've seen so far in the festival.

Will I be thought of as culturally obtuse if, for the second roundtable in a row, I cite the sole Iranian film of the bunch as the best? It's not that I love Hello, Cinema the way I do The White Balloon—though certainly enough to inspire the name of my website. It's not even among my favourite of Makhmalbaf's works, yet the film embodies the cinematic climate of the era in Iran to such an extent that I dare put it forward as the definitive Iranian film of the 1990s. Makhmalbaf is unusually frisky, playing with his public image as a cantankerous, authoritative director with a political agenda. He doesn't sand the edges of that image. Rather, with a knowing wink, he exposes the fallacy inherent in judging the "personalities" of public personae. As the title suggests, this is a film about the cinema itself, in ways that are both universal and distinctly Iranian. It's a fascinating experiment to simply compile casting auditions and lay bare the hopes and dreams and aspirations of young actors, as well as the machinations of filmmaking. More than that, in the cultural context of the time, Hello, Cinema is effectively a film about what the medium did for the Iranian society on a global scale, enhancing an image that badly needed repair after the war and the hostage crisis. There are stunning examples of this hidden in the film, some even accidental, as in the case of the young actress who wants to be cast in the film only so she can attend a hypothetical European festival and never return to the country (which, by the way, is a longer story for another day). Better yet, few movies have painted such an authentic picture of the extent to which films and their characters have been interwoven into Iranian culture and appropriated to local customs and language. Will I be thought of as culturally obtuse if, for the second roundtable in a row, I cite the sole Iranian film of the bunch as the best? It's not that I love Hello, Cinema the way I do The White Balloon—though certainly enough to inspire the name of my website. It's not even among my favourite of Makhmalbaf's works, yet the film embodies the cinematic climate of the era in Iran to such an extent that I dare put it forward as the definitive Iranian film of the 1990s. Makhmalbaf is unusually frisky, playing with his public image as a cantankerous, authoritative director with a political agenda. He doesn't sand the edges of that image. Rather, with a knowing wink, he exposes the fallacy inherent in judging the "personalities" of public personae. As the title suggests, this is a film about the cinema itself, in ways that are both universal and distinctly Iranian. It's a fascinating experiment to simply compile casting auditions and lay bare the hopes and dreams and aspirations of young actors, as well as the machinations of filmmaking. More than that, in the cultural context of the time, Hello, Cinema is effectively a film about what the medium did for the Iranian society on a global scale, enhancing an image that badly needed repair after the war and the hostage crisis. There are stunning examples of this hidden in the film, some even accidental, as in the case of the young actress who wants to be cast in the film only so she can attend a hypothetical European festival and never return to the country (which, by the way, is a longer story for another day). Better yet, few movies have painted such an authentic picture of the extent to which films and their characters have been interwoven into Iranian culture and appropriated to local customs and language.

NICK: Hello, Cinema needs no special pleading. There's no Iranian film programmed in the festival's third act, though. If you invent one and insist it's the best thing that played, we'll start asking questions, but for now, you're good. I have a few recommendations from the sidebars, too—even setting aside Todd Haynes's Safe, which I'd not only call comfortably the best film of the festival but arguably the best American film of the 1990s, give or take The Thin Red Line. I already knew I worshipped at the altar of Carol White, but I was less prepared for the impact of two exceedingly clever and richly shot manipulations of literary texts, seemingly barred from the Main Competition only by the unspoken rules against Directors Nobody's Heard Of and against Too Many Brown People. (Is that dogmatic?) One, the French-Guinean coproduction L'Enfant noir, takes Camara Laye's classic memoir of the midcentury colonial era and adapts it as the story of a teenager in contemporary Guinea. Like Camara, he navigates a tricky journey from the rustic margins of the Niger River valley to the bustling urban center of Conakry, though the film refuses to traffic in easy oppositions of any kind. The kid is also played by a direct descendant of Camara Laye, and is constantly referred to as his modern-day surrogate—thus breaking down borders of fiction and documentary in totally different ways from what Mohsen Makhmalbaf's up to, but then again, maybe not totally different. NICK: Hello, Cinema needs no special pleading. There's no Iranian film programmed in the festival's third act, though. If you invent one and insist it's the best thing that played, we'll start asking questions, but for now, you're good. I have a few recommendations from the sidebars, too—even setting aside Todd Haynes's Safe, which I'd not only call comfortably the best film of the festival but arguably the best American film of the 1990s, give or take The Thin Red Line. I already knew I worshipped at the altar of Carol White, but I was less prepared for the impact of two exceedingly clever and richly shot manipulations of literary texts, seemingly barred from the Main Competition only by the unspoken rules against Directors Nobody's Heard Of and against Too Many Brown People. (Is that dogmatic?) One, the French-Guinean coproduction L'Enfant noir, takes Camara Laye's classic memoir of the midcentury colonial era and adapts it as the story of a teenager in contemporary Guinea. Like Camara, he navigates a tricky journey from the rustic margins of the Niger River valley to the bustling urban center of Conakry, though the film refuses to traffic in easy oppositions of any kind. The kid is also played by a direct descendant of Camara Laye, and is constantly referred to as his modern-day surrogate—thus breaking down borders of fiction and documentary in totally different ways from what Mohsen Makhmalbaf's up to, but then again, maybe not totally different.

The other film I want to pitch is The Arsonist or Kaki bakar, a brooding Malaysian rewrite of the much-anthologized Faulkner story "Barn Burning." Beyond the gripping, portentous style of this hour-long mini-feature, it also registers plenty of interesting points about race, class, and power in the region, especially showcasing how free-floating anger and bitterness get passed down patrilineal channels even when young boys are perfectly clear about their fathers' demerits and reckless self-indulgence. It's amazing, too, how many of Faulkner's themes settle right into the Malaysian context without any necessary flexing. That one's on YouTube, so anybody following along with us could see it; I know Tim liked it, too. One of the real pleasures of any festival, whether in real time or in retrospect, is how an unheralded and superficially unassuming title like this can so nearly eclipse bigger guns like Shanghai Triad. That film is so ostentatious and over-worked in its aesthetics, at times for better and at times for worse, that it may as well be called Hello, Cinema. Yet I notice none of us could work up enough enthusiasm to keep it aloft in this conversation, whereas the short, sharp shocks of The Arsonist, working with a micron of the budget or the buzz available to peak-period Zhang, I expect I'll keep bugging people about for weeks, or longer.

|

|