|

|

| Photo © 2000 New Line Cinema/40 Acres and a Mule |

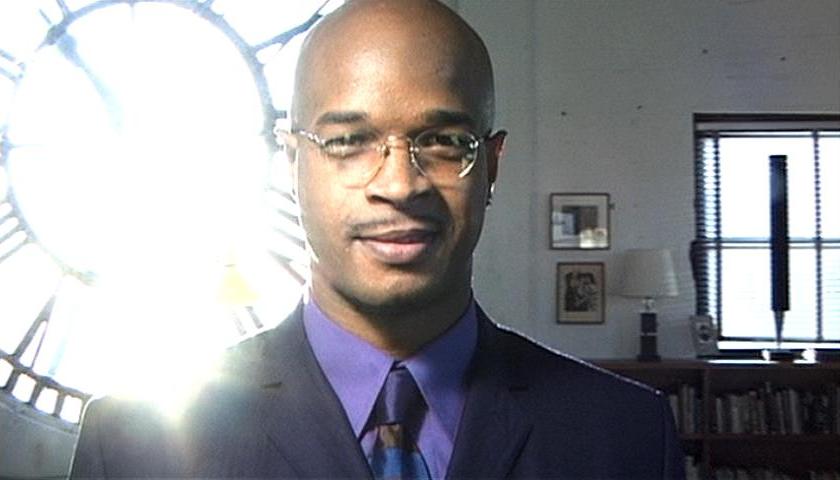

And, pace your original review, I love how the show becomes satire in ways Delacroix couldn't possibly have foreseen or orchestrated. (There's an early clue

to this in the fact that it's not him but the hideous Dunwitty who first suggests their two stars should black up, right?) Though it's an inventively weird

performance in its better moments, Wayans really isn't helping us understand whether Pierre (a) wants to get fired (b) wants to issue a colossal wake-up

call (c) even wants his show to get seen, without which it's hard to imagine (b) working, and (d) actually relishes its success or realises in any

way what a monster he's unleashed. He's an incredibly tricky character to get a handle on, but what's clear to me is that he can't be a satirist. Satire

needs principles and he has none—he sells out totally. So the definition of satire he's providing in the opening scene is itself satirical, I think.

When the show takes on a life of its own, just like the mechanical figurine on his desk feeding itself coins, he ceases to be any kind of mouthpiece for

the film's agenda—he's stopped winding it up, if you like. And by the time Savion Glover comes out, to the shock of the crowd, without the blackface

they're all wearing, Man-Tan: The New Millennium Minstrel Show has come full circle and actually scored the satirical coup de grâce

Pierre originally claims he was after. It might be my favourite thing about the film that it sets Pierre up as its prime mover but turns him into his own

victim or fall-guy, and it's something I kind of fail to expect every time I watch it.

And, pace your original review, I love how the show becomes satire in ways Delacroix couldn't possibly have foreseen or orchestrated. (There's an early clue

to this in the fact that it's not him but the hideous Dunwitty who first suggests their two stars should black up, right?) Though it's an inventively weird

performance in its better moments, Wayans really isn't helping us understand whether Pierre (a) wants to get fired (b) wants to issue a colossal wake-up

call (c) even wants his show to get seen, without which it's hard to imagine (b) working, and (d) actually relishes its success or realises in any

way what a monster he's unleashed. He's an incredibly tricky character to get a handle on, but what's clear to me is that he can't be a satirist. Satire

needs principles and he has none—he sells out totally. So the definition of satire he's providing in the opening scene is itself satirical, I think.

When the show takes on a life of its own, just like the mechanical figurine on his desk feeding itself coins, he ceases to be any kind of mouthpiece for

the film's agenda—he's stopped winding it up, if you like. And by the time Savion Glover comes out, to the shock of the crowd, without the blackface

they're all wearing, Man-Tan: The New Millennium Minstrel Show has come full circle and actually scored the satirical coup de grâce

Pierre originally claims he was after. It might be my favourite thing about the film that it sets Pierre up as its prime mover but turns him into his own

victim or fall-guy, and it's something I kind of fail to expect every time I watch it. After this bizarre redirection of motive, Sloan hops even further to being the unkempt, bathetically distressed avenger of Julius, who dies at the end of

that Mau Mau subplot which I agree ends in failure, once they become vigilante kidnappers and murderers. (What I like for a while about the Mau Mau's is

the terrifically slippy line they tread between being hotly conscientious objectors and being unthinking voiceboxes for critiques they haven't thought

through. A key line in their brilliantly stupid-smart "Blak Iz Blak" number goes, in response to racist white ideologues, 'The way Frantz Fanon put it...

they lucky I ain't read Wretched yet!') Not only is Pinkett Smith at her wit's end to improv her way through this final deranged-assassin fold in

her character, but surely Bamboozled could have saved itself on two scores by aligning Sloan's anger with that of the Mau Mau's, and tempering some

of their strangled but vitriolic anger with her cool pragmatism? It would be fascinating to see Lee consider the possibilities of lavishly educated and

privileged black media brokers working in nervous tandem with outraged black proto-activists, in the street and on the mic. Forget that Bamboozled,

like so many Lee films, raises huge questions about his penchant for dramatic structure. Is it possible that Lee, certainly hyper-educated and as mad as

hell, is too timid to think structurally, or to push his characters into these truly risky alliances? Or, more positively, do we imagine that he's so

impatient with the 1-to-1 logic of allegory that he'd rather make a movie where everyone constantly betrays themselves, in dramatic as well as moral

principle, than offer something that might look more like dogma or social recipe? It shouldn't count for nothing that we're both so intrigued by the

hurricane he whips up here, though it's hard to see how it would have harmed Bamboozled to sustain its own arcs and characters a little more

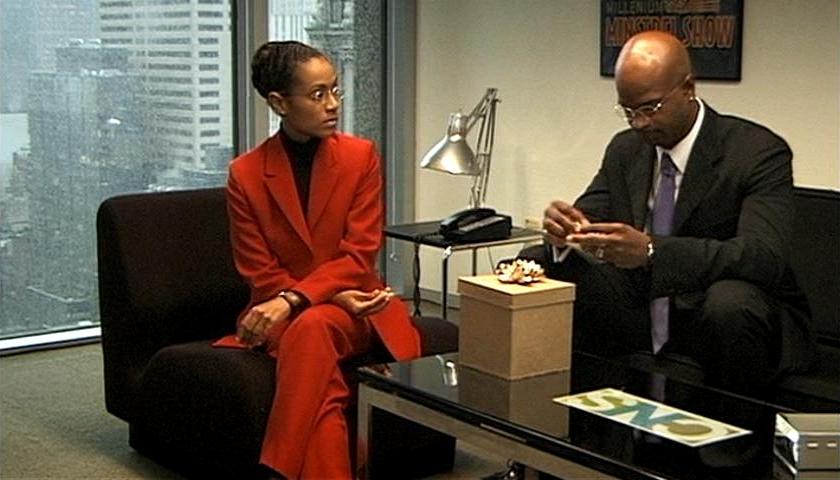

consistently. That fantastic scene where Sloan gives Pierre the tremendously barbed gift of the coinbank signals how interesting it would be for her to

start exploring her capacities for subtle subversion, her lurking passive-aggressor.

After this bizarre redirection of motive, Sloan hops even further to being the unkempt, bathetically distressed avenger of Julius, who dies at the end of

that Mau Mau subplot which I agree ends in failure, once they become vigilante kidnappers and murderers. (What I like for a while about the Mau Mau's is

the terrifically slippy line they tread between being hotly conscientious objectors and being unthinking voiceboxes for critiques they haven't thought

through. A key line in their brilliantly stupid-smart "Blak Iz Blak" number goes, in response to racist white ideologues, 'The way Frantz Fanon put it...

they lucky I ain't read Wretched yet!') Not only is Pinkett Smith at her wit's end to improv her way through this final deranged-assassin fold in

her character, but surely Bamboozled could have saved itself on two scores by aligning Sloan's anger with that of the Mau Mau's, and tempering some

of their strangled but vitriolic anger with her cool pragmatism? It would be fascinating to see Lee consider the possibilities of lavishly educated and

privileged black media brokers working in nervous tandem with outraged black proto-activists, in the street and on the mic. Forget that Bamboozled,

like so many Lee films, raises huge questions about his penchant for dramatic structure. Is it possible that Lee, certainly hyper-educated and as mad as

hell, is too timid to think structurally, or to push his characters into these truly risky alliances? Or, more positively, do we imagine that he's so

impatient with the 1-to-1 logic of allegory that he'd rather make a movie where everyone constantly betrays themselves, in dramatic as well as moral

principle, than offer something that might look more like dogma or social recipe? It shouldn't count for nothing that we're both so intrigued by the

hurricane he whips up here, though it's hard to see how it would have harmed Bamboozled to sustain its own arcs and characters a little more

consistently. That fantastic scene where Sloan gives Pierre the tremendously barbed gift of the coinbank signals how interesting it would be for her to

start exploring her capacities for subtle subversion, her lurking passive-aggressor. TR: The person we've not discussed yet in this analysis is Manray, also required to do an about-turn from malleable naif to jealous, possessive

accuser, which I'm hardly any more inclined to buy or find interesting. Frankly, it's the one section of the movie I'm tempted to write off entirely—it

almost writes itself off, making less impression in the acting or even the visuals (Kuras letting them slide from rough, poppy contrasts

into drab underlighting) than anything earlier, with the possible exception of those Mau Mau interludes shouting at the TV and taking guns out of crates.

The notion of Sloan teaming up with her brother and the gang might have been a better rescue, and creates interesting possibilities in my head, but it

still leaves the problem of what would happen to Manray, and indeed Pierre, while still making sense of Sloan. It's hard to see how any of this could end

mega-satisfactorily, given the near-insolulable problems Lee has set himself, but as it is I pretty much see it as a movie without an ending.

TR: The person we've not discussed yet in this analysis is Manray, also required to do an about-turn from malleable naif to jealous, possessive

accuser, which I'm hardly any more inclined to buy or find interesting. Frankly, it's the one section of the movie I'm tempted to write off entirely—it

almost writes itself off, making less impression in the acting or even the visuals (Kuras letting them slide from rough, poppy contrasts

into drab underlighting) than anything earlier, with the possible exception of those Mau Mau interludes shouting at the TV and taking guns out of crates.

The notion of Sloan teaming up with her brother and the gang might have been a better rescue, and creates interesting possibilities in my head, but it

still leaves the problem of what would happen to Manray, and indeed Pierre, while still making sense of Sloan. It's hard to see how any of this could end

mega-satisfactorily, given the near-insolulable problems Lee has set himself, but as it is I pretty much see it as a movie without an ending. ND: I certainly agree that Bamboozled, in its very entropy, exerts a similar fascination and vitality to those other

pictures, and I probably prefer it in some ways to Adaptation. Still, I don't think Lee is temperamentally or ideologically all that far from

being able to direct a more focused piece that would still have the virtue of a Pandora's Box-ish, unresolvable ending. As annoyingly quick as he can be

to sell out his characters (and don't even get me started on his ruthlessness toward the Jewish, Yale-educated female consultant), he obviously loves them

enough that he keeps schizophrenically recuperating the ones he seems most inclined to ridicule, Pierre being the clearest example. If he could stretch

out that frenzied ambivalence that's internal to each characterization and instead build it into some conflicts between the characters, the piece and its

ideas could still cohere in ways that would feel tragically inevitable and/or comically undecidable. Terence Blanchard's impressively melancholy score

would make just as much sense laid over a finale where Man-Tan and Womack are fighting about the show, Pierre is stuck trying to save it and to kill it,

and a fraught alliance between Sloan and the Mau Mau's (or either of them separately) was converging to sting Pierre at the peak of his dubious success.

Wouldn't that be sad, even if it were also hilarious? Spike clearly thinks they all have a point, or at least a forgivable point of view, even if he's

also prepared to stick it to all of them at different times. I suspect he harbors fears about how American critics and audiences would respond to a movie

in which all the major black characters wind up at each other's throats, since that's not the kind of dirty laundry he seems most eager to air. Oddly, though,

it's very similar to what he does wind up doing, albeit in a much more graceless way that wreaks havoc with the writing, the editing, the acting, and the

photography, and all through these prisms of hyperbolic violence and outlandish implausibility that are impossible to take seriously.

ND: I certainly agree that Bamboozled, in its very entropy, exerts a similar fascination and vitality to those other

pictures, and I probably prefer it in some ways to Adaptation. Still, I don't think Lee is temperamentally or ideologically all that far from

being able to direct a more focused piece that would still have the virtue of a Pandora's Box-ish, unresolvable ending. As annoyingly quick as he can be

to sell out his characters (and don't even get me started on his ruthlessness toward the Jewish, Yale-educated female consultant), he obviously loves them

enough that he keeps schizophrenically recuperating the ones he seems most inclined to ridicule, Pierre being the clearest example. If he could stretch

out that frenzied ambivalence that's internal to each characterization and instead build it into some conflicts between the characters, the piece and its

ideas could still cohere in ways that would feel tragically inevitable and/or comically undecidable. Terence Blanchard's impressively melancholy score

would make just as much sense laid over a finale where Man-Tan and Womack are fighting about the show, Pierre is stuck trying to save it and to kill it,

and a fraught alliance between Sloan and the Mau Mau's (or either of them separately) was converging to sting Pierre at the peak of his dubious success.

Wouldn't that be sad, even if it were also hilarious? Spike clearly thinks they all have a point, or at least a forgivable point of view, even if he's

also prepared to stick it to all of them at different times. I suspect he harbors fears about how American critics and audiences would respond to a movie

in which all the major black characters wind up at each other's throats, since that's not the kind of dirty laundry he seems most eager to air. Oddly, though,

it's very similar to what he does wind up doing, albeit in a much more graceless way that wreaks havoc with the writing, the editing, the acting, and the

photography, and all through these prisms of hyperbolic violence and outlandish implausibility that are impossible to take seriously. TR: I don't think either of us, since we're nearing the end anyway, should get started on Myrna Goldfarb, whose very name is a worrying omen for the

character assassination Lee is about to unleash; imagine garish variants on that scene for 138 minutes, and you've got easily his worst movie, She Hate Me.

There's almost always stuff in his films I want to fix, but you've gone to much more imaginative lengths redirecting the morose hell of this one's closing

movement. The parallel universe in which it concludes as forcefully as it starts is certainly an enticing one to explore. Still, I continue to find much

more to engage with throughout Bamboozled than I do in 25th Hour, a better-structured, better-shot, more consistently

acted, and far more critically well-appreciated film that I think is built on hollow foundations of male solipsism and homosexual panic which it simply

disguises better than SHM. The foundations of Bamboozled—its articulate rage, social historiography, vision of corporate politics and

apoplectic frustration with the imbalances of a placating, see-no-evil culture—remain as real and rock-solid to me as those of Levees, whether

watched in 2000, 2005, 2009, or hopefully for years to come. Sorry, that's a hideous accidental pun on levee foundations, but anyway, yes, these strike me

as his most bracing and important achievements since the early 90s. Bamboozled is a riotous mess, but I'm keen to play up the riot more than

the mess: it's such an angry one, and such a commendable instance of Lee's anger being pitched (but for Myrna) at the right targets. It's what my favourite

university tutor, a bit of a Lee fan, would have called a classic alpha-gamma, capable of swingeing faults in its own dramaturgy which muddy but never

completely extinguish the hot source of its best invective. We could wish for more careful organisation, but not for more provocative firepower, so I'll

split the difference and give it a B.

TR: I don't think either of us, since we're nearing the end anyway, should get started on Myrna Goldfarb, whose very name is a worrying omen for the

character assassination Lee is about to unleash; imagine garish variants on that scene for 138 minutes, and you've got easily his worst movie, She Hate Me.

There's almost always stuff in his films I want to fix, but you've gone to much more imaginative lengths redirecting the morose hell of this one's closing

movement. The parallel universe in which it concludes as forcefully as it starts is certainly an enticing one to explore. Still, I continue to find much

more to engage with throughout Bamboozled than I do in 25th Hour, a better-structured, better-shot, more consistently

acted, and far more critically well-appreciated film that I think is built on hollow foundations of male solipsism and homosexual panic which it simply

disguises better than SHM. The foundations of Bamboozled—its articulate rage, social historiography, vision of corporate politics and

apoplectic frustration with the imbalances of a placating, see-no-evil culture—remain as real and rock-solid to me as those of Levees, whether

watched in 2000, 2005, 2009, or hopefully for years to come. Sorry, that's a hideous accidental pun on levee foundations, but anyway, yes, these strike me

as his most bracing and important achievements since the early 90s. Bamboozled is a riotous mess, but I'm keen to play up the riot more than

the mess: it's such an angry one, and such a commendable instance of Lee's anger being pitched (but for Myrna) at the right targets. It's what my favourite

university tutor, a bit of a Lee fan, would have called a classic alpha-gamma, capable of swingeing faults in its own dramaturgy which muddy but never

completely extinguish the hot source of its best invective. We could wish for more careful organisation, but not for more provocative firepower, so I'll

split the difference and give it a B.| Awards: | |

| National Board of Review: Freedom of Expression Award | |

| Permalink | Home | 2000 | ABC | Blog |