|

| Divine Secrets Photo © 2002 Warner Bros. Pictures |

|

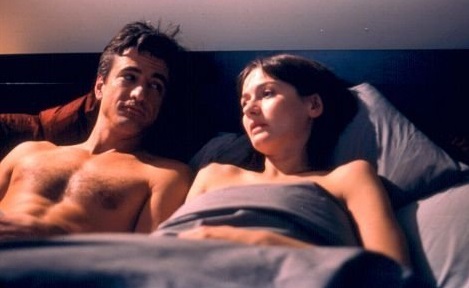

| Lovely & Amazing Photo © 2001 Blow Up Pictures/Good Machine/Roadside Attractions, © 2002 Lions Gate Films |

| Awards for Lovely & Amazing: | |

| Independent Spirit Awards: Best Supporting Actress (Mortimer) | |

| Permalink | Home | 2001 | 2002 | ABC | Blog |