| Academy Award Nominations and Winners: |

| Best Picture |

| Best Director: Woody Allen |

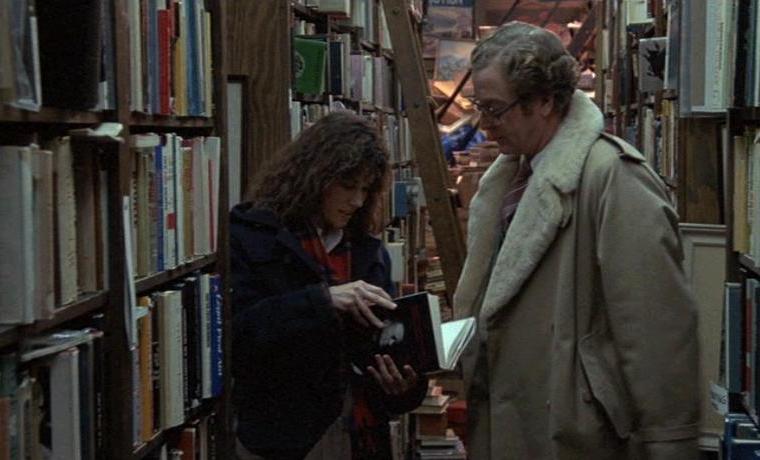

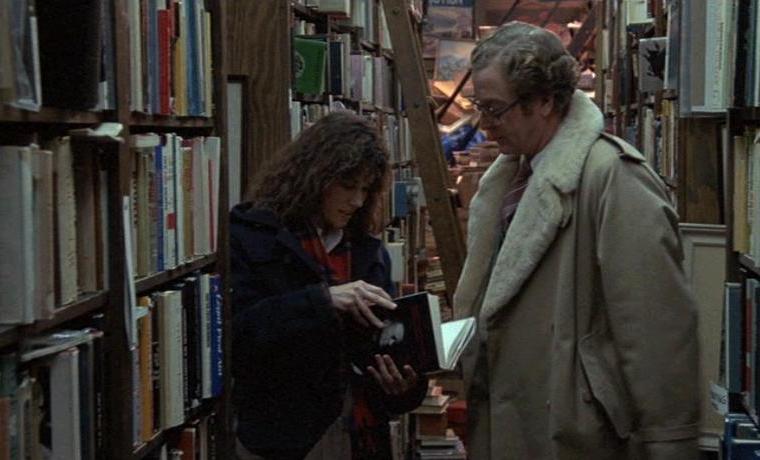

| ★ | Best Supporting Actress: Dianne Wiest |

| ★ | Best Supporting Actor: Michael Caine |

| ★ | Best Original Screenplay: Woody Allen |

| Best Art Direction: Stuart Wurtzel; Carol Joffe |

| Best Film Editing: Susan E. Morse |

|

| Golden Globe Nominations and Winners: |

| ★ | Best Picture (Musical/Comedy) |

| Best Director: Woody Allen |

| Best Supporting Actress: Dianne Wiest |

| Best Supporting Actor: Michael Caine |

| Best Screenplay: Woody Allen |

|

| Other Awards: |

| Writers Guild of America: Best Original Screenplay |

| New York Film Critics Circle: Best Picture; Best Director; Best Supporting Actress (Wiest) |

| Los Angeles Film Critics Association: Best Picture; Best Supporting Actress (Wiest; tie); Best Screenplay |

| National Society of Film Critics: Best Supporting Actress (Wiest) |

| Boston Society of Film Critics: Best Supporting Actress (Wiest); Best Screenplay |

| National Board of Review: Best Director; Best Supporting Actress (Wiest) |

| British Academy Awards (BAFTAs): Best Director; Best Original Screenplay |