#51: The Fly and Fatal Attraction

Fly (USA/Canada, 1986; dir. David Cronenberg; cin. Mark Irwin; with Jeff Goldblum, Geena Davis, John Getz, Joy Boushel, David Cronenberg, Les Carlson)

Fly (USA/Canada, 1986; dir. David Cronenberg; cin. Mark Irwin; with Jeff Goldblum, Geena Davis, John Getz, Joy Boushel, David Cronenberg, Les Carlson)

IMDb

Fatal (USA, 1987; dir. Adrian Lyne; cin. Howard Atherton; with Michael Douglas, Glenn Close, Anne Archer, Ellen Hamilton Latzen, Ellen Foley, Stuart Pankin, Fred Gwynne)

IMDb / My Page

Larval phases of cinephilia: I don't remember what movie taught me that movies could be good, or what movie taught me that a movie I liked and a "good" movie might

not necessarily be congruent. Forrest Gump was my flashpoint occasion for realizing that a celebratedly "good" movie might not be all that good. But

The Fly and Fatal Attraction acquainted me, jointly, with two more interesting ideas: that critics might trumpet a film

for being better than it "had" to be (usually implying some condescension toward genre, personnel, or earnings potential), and that films might be about

things that they didn't seem, especially to a child's mind, to be about. The latter disposition might foster the critical enthusiasm: a two-track film that

furnishes accessible generic entertainment while subliminally nourishing the noggin was one dexterous way for a movie to be "good." That both of these films

were whispered "actually" to be about the AIDS epidemic and its cyclones of fear, suffering, and paranoia surely inaugurated not only my lifelong fondness

for sustained metaphors but also my now-professional habit of looking for sexual meanings and political implications even where they don't overtly name

themselves. For some viewers, this feels like an awful lot to hang on a creaturely thriller where a guy finds himself barfing on his food in order to

slurp it back up, or a slick, sometimes chintzily lit erotic thriller with a dog-eared ending and a bunny al dente. But I think that the old bromide

"It's just a movie" is an awfully slender, polyester thing to toss onto two objects as strapping and insinuating as these.

Cronenberg's The Fly is pretty gangbusters stuff even without the barely-submerged narrative about bodily mutation, about sexual encounters yielding

monstrous results, about the copious, terrified grief of mourning someone who's falling apart right in front of you, secreted though your relations may be

from the rest of the world. The movie can't wait to get started. "What am I working on?" asks Jeff Goldblum's Seth Brundle in the opening close-up,

clearly parroting a just-posed question, and his immodest answer ("I'm working on something that will change the world and human life as we know it") has the

ring of laboratory self-confidence but also the punchy, delicious bravado of a compressed thriller making a jackrabbit start for your heart. David Cronenberg

has never thought he needed to make a long movie in order to make a muscular or a profound one, and it's immensely to his credit and to Goldblum's that Seth's

testy, eccentric bravado and his mordant facetiousness, established so early in this first scene, lends the movie enough raw, thick, vivid personality from

which to spin an entire, complicated parable. He's a great, layered character, tragic and comic in conception and in performance; The Fly was also my introduction

to the sad fact that Oscar was liable to overlook brilliant work if it came in the wrong generic package. Geena Davis also projects an astute, restless, pragmatic

intelligence that serves the movie electrically. Her witty science reporter Veronica sees what is happening to Seth so quickly, and she responds with such decisive and revelatory actions, that we're driven

to look closer into The Fly to see what Veronica sees, to grasp why this no-nonsense woman gets smitten and then pregnant so fast, why she knows to stick to her

guns about not getting into that pod, and why her feelings are too full to cut Brundle off completely, even when he's pustulating and crime-prone, and is literally

climbing the walls. Encasing and assisting these performances is a killer of a production design, with the tools for metaphysical revolution hulking inside

the desultory clutter of a dingy warehouse, with Jurassic Parkian light smoking out from the glassy base of each telepod. Are they portals to nirvana, or hell, or

transcendence or omnipotence or oblivion? It's no wonder The Fly recently made the leap to opera, and it's no wonder Howard Shore barely had to change

his score to suit that purpose: the movie traffics in gigantic but detailed emotionalism, in tremendous and essential conflicts. And sure, the maker of Scanners

still wants to explode some shit or melt some guy's leg here and there, and to see what it looks like when a human-fly remix gets disastrously re-recombined

with the corrugated steel of his own dark materials. The answer is horrible and oddly ecstatic, but no matter how ghoulish or gross

its eventual dénouement, the proud, predominating impulse of the movie is the channeling of prodigious grief. It's Brief Encounter with exoskeletons,

plus one inside-out baboon, but call me crazy, it's just as stirring and sad.

Not that anyone balks anymore when you take a critical stand on behalf of a Cronenberg film. Fatal Attraction was and is a different story: plenty

of tongues clucked the morning it scored its Best Picture nomination, and there's no way to silence the naysayers who see a glib straight-male fantasy stitched

to a hoary, misogynist cliché about the ruinous ungovernability of female desire. Because honestly, those naysayers have a point. But let's not throw

the knife-wielding banshee out with the bathwater she drowned in. This is the zestiest,

pulpiest, most compulsively engaging movie that ever over-did its blazing-oilcan location props

or its blonde, back-blown tresses for its resident Medusa. Yes,

there are entire quarter-hours that play like that scene that won't die where some poor, entangled

sop finds the convenient scrapbook of clippings where his new girlfriend/nanny/nurse has archived

all of her killings. (Can somebody drown that scene?) But has anyone watched Fatal Attraction

and not found it dangerous, sexy? Is anyone precisely sure where their sympathies do or don't fall?

The self-admiring philanderer? The anodyne family with its Westchester house? The lonely, savvy, but

deluded dame who, without need of a telepod, turns into a pterodactyl? Fatal Attraction thrives

on the febrile momentum created by editor Michael Kahn, but I love that the eight-cylinder

storytelling rush doesn't preclude quirky accents and atmospheric observations. The parents sitting

around in their underwear before getting dressed for a party. The whimpering dog who needs taking out

when Michael Douglas returns from his all-night assignation. The weirdly androgynous, spookily motionless

daughter, somehow too small for her own stuffed animals. The shrill, demanding phones. The seasick, POV track toward the crafty

intruder, perched with the wife over afternoon tea. The way Anne Archer's summary, furious

question when she hears the bad news is "What is the matter with you?" and the way Glenn Close

calls her stupid-you're-so-stupid. Also the way Glenn chuckles

as she wheedles a dog-walking day in the park out of her new conquest, and the ferocious way she bellows,

"And you get out!", kicking at Michael and letting her face sag, her breast poking

out into the unforgiving light. It's only, only and heroically because of Glenn that Fatal Attraction is as sad as

The Fly. She's the only reason its high-strung protectiveness of errant white yuppies tilts into a

despondent, hard little aria about the addictive risk of passion and the grimacing, angry sorrow

of people who know their love is trouble, for whom sex and death have an iron grip on each other, in

imagination and then in reality. For whom eros is the sound of a caged elevator slamming shut.

Not that anyone balks anymore when you take a critical stand on behalf of a Cronenberg film. Fatal Attraction was and is a different story: plenty

of tongues clucked the morning it scored its Best Picture nomination, and there's no way to silence the naysayers who see a glib straight-male fantasy stitched

to a hoary, misogynist cliché about the ruinous ungovernability of female desire. Because honestly, those naysayers have a point. But let's not throw

the knife-wielding banshee out with the bathwater she drowned in. This is the zestiest,

pulpiest, most compulsively engaging movie that ever over-did its blazing-oilcan location props

or its blonde, back-blown tresses for its resident Medusa. Yes,

there are entire quarter-hours that play like that scene that won't die where some poor, entangled

sop finds the convenient scrapbook of clippings where his new girlfriend/nanny/nurse has archived

all of her killings. (Can somebody drown that scene?) But has anyone watched Fatal Attraction

and not found it dangerous, sexy? Is anyone precisely sure where their sympathies do or don't fall?

The self-admiring philanderer? The anodyne family with its Westchester house? The lonely, savvy, but

deluded dame who, without need of a telepod, turns into a pterodactyl? Fatal Attraction thrives

on the febrile momentum created by editor Michael Kahn, but I love that the eight-cylinder

storytelling rush doesn't preclude quirky accents and atmospheric observations. The parents sitting

around in their underwear before getting dressed for a party. The whimpering dog who needs taking out

when Michael Douglas returns from his all-night assignation. The weirdly androgynous, spookily motionless

daughter, somehow too small for her own stuffed animals. The shrill, demanding phones. The seasick, POV track toward the crafty

intruder, perched with the wife over afternoon tea. The way Anne Archer's summary, furious

question when she hears the bad news is "What is the matter with you?" and the way Glenn Close

calls her stupid-you're-so-stupid. Also the way Glenn chuckles

as she wheedles a dog-walking day in the park out of her new conquest, and the ferocious way she bellows,

"And you get out!", kicking at Michael and letting her face sag, her breast poking

out into the unforgiving light. It's only, only and heroically because of Glenn that Fatal Attraction is as sad as

The Fly. She's the only reason its high-strung protectiveness of errant white yuppies tilts into a

despondent, hard little aria about the addictive risk of passion and the grimacing, angry sorrow

of people who know their love is trouble, for whom sex and death have an iron grip on each other, in

imagination and then in reality. For whom eros is the sound of a caged elevator slamming shut.

#52: Adam's Rib

(USA, 1949; dir. George Cukor; cin. George J. Folsey; with Spencer Tracy, Katharine Hepburn, Judy Holliday, Tom Ewell,

David Wayne, Jean Hagen, Hope Emerson, Clarence Kolb)

(USA, 1949; dir. George Cukor; cin. George J. Folsey; with Spencer Tracy, Katharine Hepburn, Judy Holliday, Tom Ewell,

David Wayne, Jean Hagen, Hope Emerson, Clarence Kolb)

IMDb

As I have previously indicated, I was not just a fan or a student, I was a citizen of Katharine Hepburn

during my high school years, as is partly indicated by the fact that, in this 2008 version of the Favorites Countdown, she is tied with two other actresses

for the most entries on the list (four apiece, as have Julianne Moore and Nicole Kidman). I can't decide whether my ardor for Hepburn—which has mostly

endured even as her self-marketed persona has lap-dissolved into a fuller, more adult vantage on her virtues and flaws—makes it more or less surprising

that in all these years I haven't corrected a major aporia in my viewing completism. Which is to say, I have only seen three of her nine nationally consecrated

screen-partnerships with Spencer Tracy. No Hepburn fan would permit the same lapse in relation to her Cary Grant collabos: buoyant, thoughtful, full-bodied,

and frequently odd affairs as distinctive now as they were then. I am sure the Hepburn-Tracy vehicles have their charms, but even Woman of the Year,

the lightning rod that inaugurated their partnership at all levels, falls short of the primo experience of, say, top-flight Astaire & Rogers, and I suspect

a similar differential between medium-grade Astaire & Rogers like Follow the Fleet and medium-grade Hepburn & Tracy like, from what I gather, Desk

Set or State of the Union. By all means, tell me if I'm wrong. But there's a two-way hurdle here. 1) It's hard, at least for me, to see in Tracy

what Hepburn saw in Tracy; the films and the actress often get soft on the barest modicum of verve or vulnerability, and he's grumpy and high-horsed an awful

lot of the time. And 2) it's hard to see in Hepburn, when she's with Tracy, what I most love about Hepburn when she's not with Tracy; around

"Spence," she's always apologizing, kneeling on the floor, lamenting even her victories. This is probably closer to real Hepburn, at least in some ways,

or at least by middle age, or at least in relation to Tracy, than are Susan Vance or Tracy Lord or Alice Adams, but I'm not

sure she's yare.

So thank God for Adam's Rib, because even if it doesn't quite match the high screwball watermarks of It Happened One Night or The Lady Eve

as I once thought it did, it's a generous and delicious slice of old-Hollywood cake. More than that, it poses the perfect rejoinder to my Hepburn-Tracy

hangups, proving how devilishly entertaining their partnership could be, how Tracy had it in him to be just as game and surprising and interesting as his

lady love, and how the off-putting psychodynamics of his fogeyish disapproval and her ill-fitted submissiveness can be fascinating and revelatory in the

right, scrumptiously enveloping context. The film starts on neither of the leads but on Judy Holliday's Doris Attinger, burlesquing the opening of The

Letter by pathetically trailing her husband Warren to an afternoon assignation. Between bites of her high-carb nut bars, meant to feed and to steel her

stomach, Doris fires pistol shots wildly around the love nest. It's a well-known story that Hepburn, Tracy, director-friend George Cukor, and screenwriters

and best pals Ruth Gordon and Garson Kanin wanted to get Holliday the job of reprising on-screen her triumphant lead performance in Kanin's stage hit Born

Yesterday (as she did one year later, to Oscar-winning effect). As PR prep, then, fair-sized chunks of Adam's Rib have been written, acted, and filmed

to show Holliday off, as in the long take where Hepburn, as Doris' riled defense attorney Amanda Bonner, interviews her client: "And after you shot him, how

did you feel then?" Holliday dwells on the question in her tearful and spacey way, and then answers: "Hungry." I like Holliday's performance even better

when it's quiet; she just loves it, from the background, when a star witness played by Hope Emerson (another soon-to-be Oscar nominee) lifts the prosecuting

attorney played by Tracy seven feet in the air, in order to prove some ineffable, absurd principle of women's strength being equal to men's. Singin'

in the Rain's Jean Hagen is also a reliable, nicely muffled treat as the husband's vapid girl on the side, Beryl Caighn. If David Wayne is a bit too

relentless as Kip, the swishy womanizer next door, who homes in even harder on Hepburn's Amanda when her courtroom battle with her hubby-opponent gets too hot,

he at least scores the film's most savory line: "Lawyers should never marry other lawyers. This is called inbreeding, from which comes idiot children, and more lawyers."

Due credit, then, to all the accentuating pleasures of supporting players and verbal wit and George Cukor's typically light, pastryish direction, which can

still turn nimbly around to confront some real ugliness. And Hepburn and Tracy are constantly making him do that. Yes, they're both aces with the comedy stuff, and

they flirt with each other shamelessly, whether in stock footage at their bungalow, or in the sweetly

sexy scenes where they keep dropping pencils in court so they can goo-goo at each other under the table, and she can show off the loopy hemline of her slip.

But Tracy's Adam is hugely disappointed in Amanda's Barnum-style approach to the case. And she's steamed that he doesn't get why Doris' hazy, gun-blasting assault on her

husband demands a carnivalesque social referendum on men, women, and how they view each other. So, yes, Amanda is making the Matthew McConaughey Time to Kill

argument—"She's innocent, because the culture is so awful!"—and on these grounds, you can forgive more of Tracy's admonishing outbursts than you otherwise

might, just as you accept more of the dizzy distractions that Amanda, Hepburn, Cukor, and the script keep throwing at us. They're all frosting, very nicely,

a pretty inane premise. Charm, aplomb, and conviction go a long, long way. He says, "You just sound so cute when you're cause-y" as though it's a real,

besotted compliment, and she wings about in her two-tone chicly asymmetrical single-lapel lawyering suit like she's ready to teach all of us a thing or two about

gender and lawyering and looking freaking fantastic without seeming to call any attention to it. Makes me hate that by the time she's giving

her closing statement, she looks a lot more like the star of Saint Joan. That's another grim undercurrent, but there are many more, and worse: Tracy's Adam

slapping Hepburn's Amanda, hard, leading to a close-up of Amanda in thoughtful, curtain-dropping horror that's one of the most interesting close-ups in Hepburn's

whole career. Hepburn debating the archaisms and impossibilities of marriage, all but facing the audience, while cast alongside the married man that everyone

knew she was living with. Spencer, I mean Adam, making fun of Amanda's "Bryn Mawr" accent. Spencer, I mean Adam, demanding his rightful dominion over Hepburn,

I mean Amanda, as against the insinuating lavender claims of Cukor, I mean Kip. Amanda exploding in terrible, breathless, rageful tears and begging Adam to at least

try to understand her, to try to adjust himself to her, for a goddamned change.

It all cuts rather close to the bone, as voyeuristic in its way as anything in Kanin's "intimate memoir" Tracy and Hepburn, two decades later.

But the intimacy of all involved also works delightfully in the lighter scenes: Cukor can squat the static camera right in the

couple's empty bedroom and get a whole, lovely scene of conjugal characterization as they flit in and out, getting dressed and going to the loo, and

calling out to each other from offscreen closets and vanity counters. There are dozens of flavorful takeaways: the way Tracy erupts, twice, on the word "competitor";

the underplayed absurdity of Jean Hagen's answers from the witness box ("What kind of a noise?" / "Like a sound, like a loud sound going off!"); the licorice

gag; the proscenium intertitles in birthday-party font; the scene of Tracy demonstrating how to cry on cue ("Us boys can do it, too, we just never think to").

"Your Honor, I object to this farce," Adam bays out during the trial. I am positive there's more going on in Adam's Rib than just the farce, but your

Honor, I don't object to any of it.

#53: Bring It On

(USA, 2000; dir. Peyton Reed; cin. Shawn Maurer; with Kirsten Dunst, Eliza Dushku, Jesse Bradford, Gabrielle Union,

Clare Kramer, Nicole Bilderback, Richard Hillman, Tsianina Joelson, Nathan West, Huntley Ritter, Shamari Fears, Natina Reed, Brandi Williams, Richard Hillman, Ian Roberts)

(USA, 2000; dir. Peyton Reed; cin. Shawn Maurer; with Kirsten Dunst, Eliza Dushku, Jesse Bradford, Gabrielle Union,

Clare Kramer, Nicole Bilderback, Richard Hillman, Tsianina Joelson, Nathan West, Huntley Ritter, Shamari Fears, Natina Reed, Brandi Williams, Richard Hillman, Ian Roberts)

IMDb // My Full Review

An infelicitously timed telephone call from my father made me late to the theater for my first screening of Bring It On.

I hate to be late, and I'm never ever late to movies. Making matters worse, I made my friend

late, too, which means that we didn't even know until the second time we watched Bring It On about the all-cheering

character introductions at the film's beginning. In other words, having already gorged ourselves gleefully on the movie's

unflagging and ennobling pop energy, the pristine palette, the tartly drawn characters, the strength and economy of the

editing, the freshness of the script, the giddy spectacle of the cheerleading routines, the infectious teen spirit of the

actors, the robust but delicate tenor between spoof and sincerity, we waited and waited for the DVD release (having caught

Bring It On on the very last night of its second-run tour through Ithaca, NY) and discovered to our delight that

there was even more movie to enjoy. Bring it on, indeed!

I haven't met anyone who thinks Bring It On is a bad film, though I can only assume such characters exist. Rather,

in my experience, Bring It On cleaves its viewership into two camps: those who see a merely adequate but derivative

and utterly unspecial movie about cheerleading forchrissakes, and those who see the Grand Illusion of modern

high-school comedies. I have found that it is difficult to communicate across the divide between the agnostics and the

devotés. It's even a little bit difficult to communicate among the devotés, because for the converted, to

be in the presence of Bring It On is to be bathed in total, self-evident pleasure. Explanation falters out of what

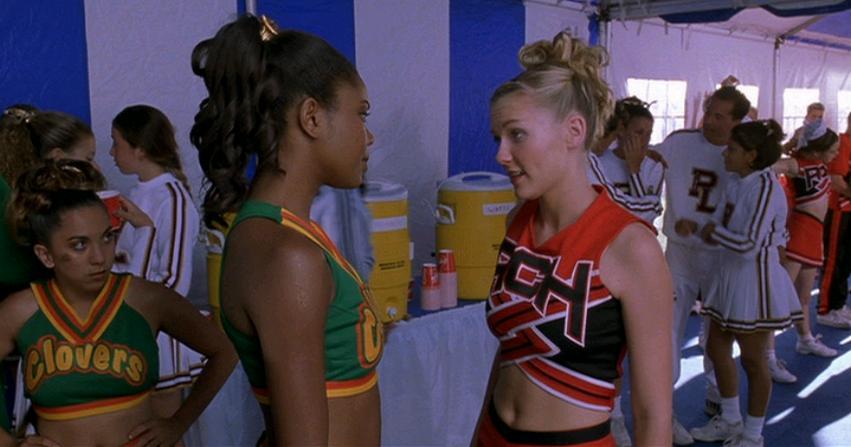

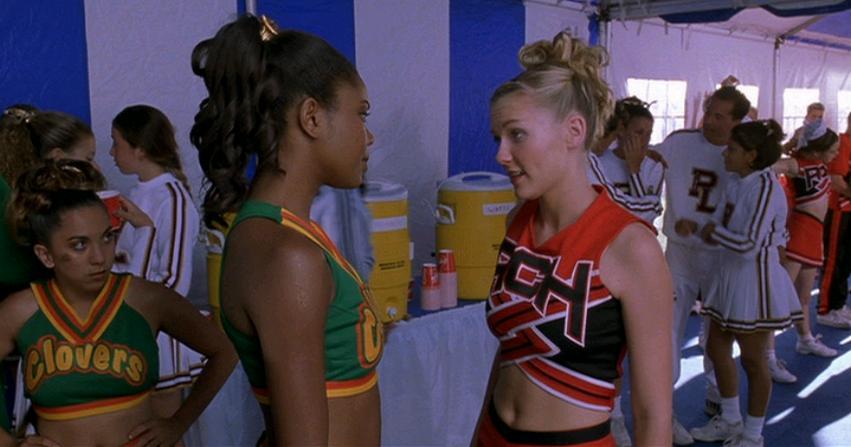

amounts to unnecessity, but let's try. Let's start with the single frame I have reproduced here, from a mutedly climactic

scene where duelling squad captains Torrance (Kirsten Dunst) and Isis (Gabrielle Union) exchange succinct, slightly tense,

but generous advice about how to keep their cheerleaders in perfect formation during their respective routines at the

national competition. Note that almost every primary color as yet discovered by man is evidenced in this shot, but the

overall effect is more engaging than garish. Note that the strong, diagonal, and yet flattering designs for the uniforms

of the Rancho Carne Toros and the Compton Clovers toe a precocious line between a silly, unexploitative sauciness and a

tough, sporting conviction about the tasks at hand. Note that the framing plays up a symmetry between Torrance and Isis,

conveying that these longtime rivals have entered into something like a mutual understanding, even as the sharp contrast

between the two backgrounds—blue and white color bars behind Isis, a percolating crowd behind Torrance—continue to

set them off from each other. Actually, I emend myself: Torrance is the Prime Meridian of this shot, exactly dividing the

two background fields on either side of her, subtly reminding us that the scene isn't so much about a standoff between the

mavens as a turning point within Torrance herself, who now meets Isis as a fond equal without relinquishing any of her own

competitive zeal. Chicas, you can pause or replay Bring It On liberally and find care, undertones, and tiny formal

ironies like these. It isn't Orson Welles, but for crying out loud, when was the last time color, composition, blocking,

and design were this precisely calibrated in a teen comedy?

And not just any teen comedy, either, but one with a bevy of diversely likeable characters? Starring a pedigreed teenage

actress who bounces right into the kind of role that pedigreed teenage actresses often convince themselves, understandably,

that they should avoid? Scribe Jessica Bendinger knows what she's doing, basing things around a somewhat standard-issue

plot for movies like this (the rich white girls are stealing the poorer black girls' routines, but the latest white girl

Feels Bad About This!), but sticking the expected resolution (the white girl makes guilty, philanthropic amends) into the

center of the picture, where it elicits a properly brusque refusal from characters who don't want or need to be condescended

to. Bring It On manages to get its PC cupcake and eat it, too: double-standards are memorably laid bare, but a

strict, objective meritocracy remains firmly in place. That means, the best bringers still win, and how! The final plume

in the movie's hat, or maybe the pom-pom in its hand, is director Peyton Reed, whom nobody seems to have told that teen

flicks require impersonal direction, largely to keep the actors in frame and under Seventeen lighting. Instead,

Reed shapes the scenes he wants, none of them better than a piquant flirtation at a bathroom sink that doesn't need any

dialogue. He even wrings some fresh laughs from one of those boilerplate sequences I hate, the kind of montage in which

19 stereotypes and walking punchlines fail at a task, nearly failing at their own humanity, so that the 20th person looks

like a comparative gem. Bring It On isn't a comparative gem. It's just a gem, rallying all the pep that pop movies

can muster and sticking with you afterward.

#54: Postcards from the Edge

(USA, 1990; dir. Mike Nichols; cin. Michael Ballhaus; with Meryl Streep, Shirley MacLaine, Dennis Quaid, Gene Hackman,

Richard Dreyfuss, Robin Bartlett, Annette Bening, Rob Reiner, Mary Wickes, Dana Ivey, CCH Pounder)

(USA, 1990; dir. Mike Nichols; cin. Michael Ballhaus; with Meryl Streep, Shirley MacLaine, Dennis Quaid, Gene Hackman,

Richard Dreyfuss, Robin Bartlett, Annette Bening, Rob Reiner, Mary Wickes, Dana Ivey, CCH Pounder)

IMDb

For reasons I have specified above, Sandra Bernhard would have won my support for the Best Actress Oscar

in 1990, even though Without You I'm Nothing

is obviously not the sort of vehicle to which the Academy pays any

mind—not only because they resist formal experiments, but because they

don't even like to laugh. Unless, that is, the responsible party is

someone like Meryl Streep, whose tragic-dramatic prestige conversely

assures them that a little merriment never killed anyone. In Postcards from

the Edge, Streep sufficiently tickled the voters' funny bones to at least score

her a nod the year Bernhard should have won. Streep and Bernhard: few

people's idea of a seamless pair, but they do share a knack for zeroing

in on their targets, especially their punchlines, without hiding the

mechanics of how they're doing it. Streep is a kind of performance

artist: you watch the woman she's playing, and you simultaneously watch

her play that woman. Sometimes, yes, this method can feel a bit

clinical, especially when, as in Out of Africa or Dancing at Lughnasa, the tricksiness of her preferred style is out of proportion

to the dullness of the character. At her best, though, Streep's "intellectual" quality is actually a conduit for a bountifully

generous entertainer's impulse: both the character and its construction are invigorating spectacles, and for an audience

to be gifted with both at once is like following a full and zesty meal with a rich and flavorful dessert. You can even eat

them at the same time! You can go back and forth! Meryl's here to give give give. Take what pleases you. Enjoy it all.

She, at least, is having a ball.

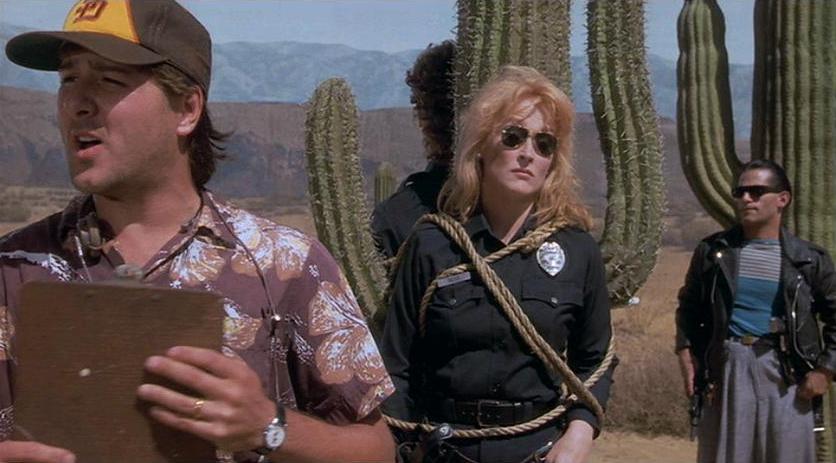

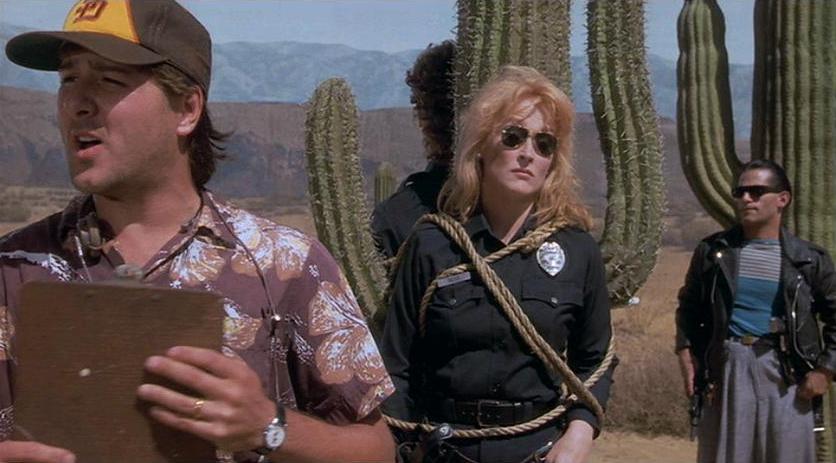

Postcards from the Edge hails from that period in Streep's career when she suddenly and understandably appeared apprehensive

about forever playing piet?s and martyrs and wailing women from across the Earth's four corners. She had a Funny Period

the same way Picasso had a Blue one, and though I haven't actually seen any of its other avatars (She-Devil, Defending

Your Life, Death Becomes Her), her work in Postcards

is so lively in detail that, again, you feel like you're getting

several performances for the price of one. Meryl tokes up, she zones

out, she trips, she sings twice, she shoots guns twice. But the real

action is in the shifting sands of her face and her tiny symphonies of

physical accents, whenever she's about the deceptively simple business

of selling a line or a scene, or even a fellow actor's performance.

Watch what a comic tour-de-force she finds just by crouching among a

wire-rack of costumes on a movie-set, her eyes and her relative posture

our only inlets into a twelve-tone coloratura of comic humiliation.

Waking up, unexpectedly, in a rehab center, she parses out into

multiple comic beats what many actors would fold or purée into a single

affect: her dazedness, her breath, her shame, her fright, the blinding

whiteness of the light and the room, the puzzling discovery of a

plastic hospital bracelet around her arm, her dawning recognition that

news of her predicament has certainly, already sprinted to undesired

destinations. Carrie Fisher has filled her autobiographical script with

choice one-liners and her trademark sensibility for observing life

askance. "I have feelings for you," confesses a sun-kissed Dennis

Quaid, to which Streep responds, "Well, how many? More than—two?", and

while the line is a great gift to her (and there's way, way more where

that came from), her muffled, almost foggy playing of it is a cadeau to Quaid, an earnest tryer who rarely knows, and

certainly didn't know in 1990, how to anchor a scene or vary its

rhythm. Streep forces him to shake things up, just like she keeps

Shirley MacLaine's campy grandiloquence on a liberal but certain leash,

letting her do her Thing, even getting her own zappy charge out of it,

but also keeping everyone in service of the movie, especially of

Fisher's voice. Like Streep, Fisher is possessed of a sophisticated

hamminess that she isn't at all bashful about trotting out, so it's no

surprise that the two women are such ample enthusiasts and protectors

of each other. Fisher's overriding and self-analytical theme, that she

has no idea who she is or who she should be, or whether those two

concepts even remotely go together, also creates a winning ironic frame

for Streep's own chameleonism: watching her change shape and mental

fabric, even within seconds, weds the familiar pleasures to some new

questions about exhibitionism and avoidance.

Watching so many modern film comedies, I can't help wishing that they

had been made fifty years ago; it's the single genre where the drop-off

in quality strikes me as the most precipitous, largely because

filmmakers' confidence in things like words,

speed, and economy have shriveled to the size of a maraschino cherry. Postcards, though, is a rare example

of a film that wouldn't be funny at any brisker pace, or with more rapid-fire actors. A more intricate style wouldn't add

much—and besides, at zero cost, cinematographer Michael Ballhaus is already having fun moving Streep around the foregrounds,

middle-grounds, and backgrounds of his shots, and she mines different kinds of comic gold depending on where she is: a miracle.

Finally, in a major departure from most Hollywood comedies about Hollywood, Postcards

feels credibly conditioned in what the industry actually is and how a

set might actually feel: the anodyne hallways and lots and trailers,

the dead intervals between camera set-ups, the way in which Streep's

humbled B-lister keeps getting into personal fender-benders with

producers, directors, wardrobe assistants, and crass starlets.

Hollywood as a way of life, with its own cadences and its own soil,

tillable for its very own jokes, is largely divorced from the clichés

of celebrity and grotesque wealth. This Edge, then, is a terrifically

accessible place, recognizable as a movie about parents and children,

about Achilles heels, about the weeks and months of life that seem

totally ceded to personal embarrassment, whether or not you have a drug

problem, whether or not your mother is Debbie Reynolds Shirley MacLaine Doris Mann. For her part, Meryl Streep will return

at two more points higher on this list, in more recognizably Streepish vehicles, but of all of her movies, this is the one

that's most easily and comfortably open to visitors, especially old friends, and it never ages or disappoints.

#55: Titanic

(USA, 1997; dir. James Cameron; cin. Russell Carpenter; with Kate Winslet, Leonardo DiCaprio, Billy Zane, Gloria Stuart,

Bill Paxton, Frances Fisher, Kathy Bates, Bernard Hill, Victor Garber, Jonathan Hyde, David Warner, Suzy Amis, Danny Nucci, Jason Barry, Ioan Gruffudd)

(USA, 1997; dir. James Cameron; cin. Russell Carpenter; with Kate Winslet, Leonardo DiCaprio, Billy Zane, Gloria Stuart,

Bill Paxton, Frances Fisher, Kathy Bates, Bernard Hill, Victor Garber, Jonathan Hyde, David Warner, Suzy Amis, Danny Nucci, Jason Barry, Ioan Gruffudd)

IMDb // My Full Review

When I first started teaching film, Titanic was invaluable to me, because every single student in my course had seen

it, often more than once. As a result, for shared, shorthanded examples of camera angles, color filters, process shots, the comparative

scope of a scene vs. a sequence, etc., and just as living proof that movies can unite people and endow us with common language

and experience, Titanic was—in the treasure-hunting lingo of Brock Lovett & Co.—a trove,

a jackpot. These days, it's hardly worth the trouble of invoking Titanic, because cracking the thick crust of derision

or, at best, embarrassed affection is too arduous and digressive a task. Talk about hitting an iceberg: I recognize that even

in 1997 and 1998, plenty of people were roundly unseduced by James Cameron's ballad of Jack and Rose. By now, though, Titanic

seems to have sunk from a global preoccupation to an abashed recollection or a blacklisted

memory.

Both the initial embrace of Titanic and its harsh disavowal, at least in the crowds where I hang out, betray a

degree of emotionalism uncommon in the giddy world of movies—testament not only to how the film distinguishes

itself from other epic-scale blockbusters by stoking emotion instead of cultivating detachment (it is, in this regard, the

anti-Matrix) but to how the sinking of the Titanic itself,

with all due respect to the people who died, resonates more in the history of affect than in any real chronicle of worldly

consequence. Of course the event was triggered and conditioned by much vaster and more complicated forces—industrialism,

social stratification, a booming market in luxuries, a new impetus behind global travel—but it's hard to feel as though

any of these concepts operate in any truly complex way within the story of the Titanic, which unfolds as cleanly and

simply as a parable. The poor paid for the luxuries of the rich, but death leveled them all. Idealism and ambition ran afoul

of a major shoal of hubris. Many, many people died at once, and the foregoing circus of media jubilation around the ship's

maiden voyage (as damp a phrase as anyone ever coined)

made the deaths somehow more awful by making them so public—a bleak irony, too, since

part of the horror of this story is the dark, freezing, lonely privacy in which the ship met its fate, so chillingly

captured by that one extreme long shot of the distress flare, a pathetic white comma on the blank black sheet of the oceanic night. Titanic has an ideally sized plot for a movie, and for eliciting mass enthusiasm and identification, because despite

the size of the ship and the scale of its infamy, the story's contours remain so manageable. In absolute contrast to something

like the JFK assassination, the essential gist and ramification of the story can be quickly known, and since popular imagination

has kept it afloat within an envelope of gently precautionary pathos, the tale offers a perfect porthole into broad

fields and brushstrokes of feeling: romance, awe, sublimity, sentimentality, gravity, fear, manmade inequities as well as cosmic ones.

Cameron's script isn't nearly as ambitious as those he wrote for the Terminator films or for the exemplary Aliens.

Nonetheless, his extraordinary visual acumen and his keen regard for the audience's investments even

in kinetic and logistic-heavy scenes prepares him perfectly as the director to animate Jack's doomed resourcefulness,

Rose's coltish but galvanized resolve, the shipbuilder's avuncular regret, and all those "minor" moments of couples laid together in bed to their final rest,

strangers gripping to handrails, waitstaff bolting through the corridors, deckhands crumbling in the face of the panicking

crowd, "survivors" condemned to watch what they have just escaped. And he keeps all this in balance while presiding over a

gargantuan, exacting, and detailed set, a mythic vision to hold alongside Griffith's Babylon.

Shame about the dialogue, and the high school lit-mag deployment of suicide as a plot device. I know, I know: that song. Many of the performances could stand

some tweaking (more than that, in Billy Zane's case), even allowing that they've been evacuated of nuance so as to approximate

the idioms of shipboard fictions, and also to purvey the script's distilled emotional states in as unobtrusive

a way as possible. Too bad that, for all the justified finger-wagging at class oppression onboard, the world below decks is

still something of a fratboy revue of gambols and beer steins, and the story still ends with a crafty and hardworking prole giving

his life so that an aristocrat might live. If Titanic were truly building to an intellectual or editorial point, it

would have a hard time persuading anybody that Jack's death offered the gorgeous, necessary precondition for Rose's rich,

full life of riding ponies and turning pots. But palpably, these aren't the waters in which Titanic means to sail,

at least not essentially. Every shot, every terrifically paced and judged cross-cut and interlude—increasingly so, in

the film's formally heroic second half—squares the viewer right inside a romantic imagination of beauty and danger that movies

almost never attempt anymore. The range of sentiments and the visual lucidity through which Titanic presents itself

are tangible and recognizable to almost anyone of any age, and maybe that sounds like a backhanded compliment, but I mean it as an endorsement

of the film's refusal to be cynical, or to be simply and flatly procedural like The Poseidon Adventure or Airport,

or to wave the flag of its own virtuosity in as shrill and off-putting a way as James Cameron does in his public appearances.

The movie knows when to stop showing us smashed hutches and looming rudders against the sky and to contract instead around

moments like the one that always, always gets me: Rose, secured on a lowering lifeboat, realizing as Jack recedes in an

extreme low-angle shot that the life she is saving for herself is not one she wants to save, and so she clambers back onto the

dying animal of the Titanic and runs right back toward Jack. The most sophisticated dramaturgy in the world? No—but

at least for me, it reverberates just as much as watching Dorothy walk outdoors into Technicolor or Luke discover that his

archenemy is his father or a treasured, long-buried childhood toy melt away in a furnace. Call me crazy, but I'll go down with this ship every time.

#56: Frankie & Johnny

(USA, 1991; dir. Garry Marshall; cin. Dante Spinotti; with Michelle Pfeiffer, Al Pacino, Hector Elizondo, Kate Nelligan, Jane Morris,

Nathan Lane, Glenn Plummer)

(USA, 1991; dir. Garry Marshall; cin. Dante Spinotti; with Michelle Pfeiffer, Al Pacino, Hector Elizondo, Kate Nelligan, Jane Morris,

Nathan Lane, Glenn Plummer)

IMDb

Michelle Pfeiffer may well be the most beautiful actress in Hollywood, and though she's rarely cited among the Streeps and

and Moores, her talent is terrific and underrated: she's extremely attuned to her characters, capable both of mannerism and

intuitive openness, and malleable to the divergent needs of a wide range of directors, genres, and projects. Despite

all of this, however, she seems genuinely unsolicitous of attention. One almost gets the sense that she'd prefer to go

unnoticed, and that it's both a blessing and a curse for her to be so skilled and well-rewarded in a profession that requires

such extraordinary levels of scrutiny. She doesn't work that often, and when she does, she frequently opts for parts in movies that feel destined to escape critical or popular regard. Sometimes the parts aren't even that

good, and you wonder, why is an actress of Pfeiffer's caliber and acclaim willing to break her reclusive patterns in order

to star in Up Close and Personal or To Gillian on Her 37th Birthday? Why is it that even when she stars in a

film with a built-in pedigree, like the Oprah-certified The Deep End of the Ocean or the Pulitzer-winning A Thousand Acres,

the films don't ignite, despite how good she is in them? Is some kind of self-fulfilling prophecy at work? Are audiences

so intimidated by her Garboesque appearance that they miss how proudly middlebrow her tastes run, how, at least on screen, her

fundamental guardedness gives way to such emotional transparency? Even in upper-crusty endeavors like Dangerous

Liaisons and The Age of Innocence, she telegraphs emotions, very subtly shading them but still making them big

enough for large crowds to relate to—as opposed to, say, the more architectural acting styles of co-stars like Glenn Close

and Daniel Day-Lewis. Even while traveling among totally different filmmaking idioms and adjusting her performmances accordingly,

the uniting feature is that she always finds the identificatory points, situating her characters on a perfectly even keel with

the audiences (especially, you feel, the women) who will be watching her, and stressing the common humanity that links Age's Countess Ellen Olenska, tainted by divorce and decorously spurned by the late

19th-century Manhattan aristocracy, with Ocean's Beth Cappadora, a wounded Wisconsin mom who likes milk with her pizza.

In my mind, this paradoxical blend of glamour and agoraphobia, these keynotes of humility and sadness that connect the women

she plays, reach their apotheosis in Garry Marshall's Frankie & Johnny, exactly the sort of film that tends to zip straight

from a quick release to a rental-store shelf. Regardless of how capably Pfeiffer modifies and recalculates her looks

in almost every role, the rigid preconception that she was too beautiful for a part played onstage by Kathy Bates muffled

any hope of her performance being taken very seriously. Having Marshall's name attached as director couldn't have helped,

but for both the star and the director, the film still represents their peak accomplishment: her apex in a career of admirable

successes, his solitary but impressive excuse for calling himself an artist. Frankie & Johnny delivers

one of the most elusive chimeras in mainstream moviemaking: a romance that has the look, the rhythm, the one-liners, and even

the premise of a comedy but is actually not a comedy. Its low notes and minor chords are just as foundational and just as

constant as its bright spots and perky exchanges. Its resolution, however proudly optimistic, is also quite tentative.

In sum, it's an adult vision of two complicated people converging, finding an ointment but not a cure for the ways in which

they have been hurt. It's a romance where people remain throughout who they were in the first scenes. The script, adapted

by Terrence McNally from his own play, expands the action and widens the cast, but it brooks remarkably few compromises with

the testy, nervous, mercurial attraction between Frankie and Johnny: the way he comes on too strong, smitten but also a little

arrogant; the way she refuses what seems to arrive too easily and unexpectedly at her feet; the way he romances her and pleads

with her but occasionally betrays something ugly; the way she loosens up and has some fun testing the waters, but never quite

stops building up walls, slamming doors, and changing her tune. Pfeiffer, owning the movie while the wonderful Pacino agreeably serves it

back to her, is eminently believable at every instant. She's funny and tart at work, she relishes small victories like bowling

a strike and winning at handball, she keeps scenes alive while acting behind a countertop or inside a cramped New York

bathroom. In the terrific, mood-setting opening—the one moment in the movie when we leave the city—Frankie has the

nervy, suspicious jitters while visiting her family in Altoona, PA, but her candor and clarity are beyond reproach when she

confides to her mother at the kitchen sink, "Maybe I'm not the happiest person in the world, but that's not your fault."

Like Pfeiffer herself, Frankie wants to be left alone, but she also wants to be found.

Garry Marshall doesn't quite prove in Frankie & Johnny that he's got a firm handle on the known world—meaning,

for example, that struggling busboys who quit to be screenwriters still live in fantastic two-story loft apartments. But compared

to the laundered, insane exuberance of Pretty Woman, with its constant denials of its lurid and reactionary content,

Frankie & Johnny feels wise, unpushy, generously ceded to the actors and the writer, peppered with punchlines and gag

shots but willing to let top-drawer cinematographer Dante Spinotti do his thing.

Seemingly truncated plot threads, like Pacino's reconnection with his ex-wife and alienated children, actually gain strength

from being peripheral: there's a credible, refreshing sense in the movie that Frankie and Johnny's courtship does not subsume

every one of their private voyages and trials. Even the song score Marshall chooses is of an utterly different species than

Pretty Woman's market-friendly avalanche of radio hits; it privileges the expected and shimmering Debussy, a funkily melancholic title

track by Terence Trent D'Arby, and a song called "It Must Be Love" by Rickie Lee Jones that, like the movie,

is either an uptempo ballad or a cautiously muted pop declaration, depending on how you look at it. The production design

of the diner is excellent. The supporting notes supplied by a then-unknown Nathan Lane and the perennially underutilized Kate

Nelligan are delectable. A faux-rose that Johnny whips up out of a dyed-red potato, a fork, and a celery stalk swipes the

all-time movieland prize for whimsical, endearing diner chic, narrowly squeaking past Jeffrey Wright painting Claire Forlani's

portrait in his pancake syrup in Basquiat. Frankie & Johnny is so unpretentious that its fine, layered, beautifully

coaxed instincts at serving its script and its characters and its audience are easy to overlook. Don't.

#57: Min and Bill

(USA, 1930; dir. George W. Hill; cin. Harold Wenstrom; with Marie Dressler, Wallace Beery, Dorothy Jordan, Marjorie Rambeau, DeWitt Jennings, Don Dillaway)

(USA, 1930; dir. George W. Hill; cin. Harold Wenstrom; with Marie Dressler, Wallace Beery, Dorothy Jordan, Marjorie Rambeau, DeWitt Jennings, Don Dillaway)

IMDb // My Page

If, as surely does happen, Oscar-winning actresses

congregate in heaven for their own exclusive socials, Marie Dressler

sticks out like more than a sore thumb. Here was an actress of such

stout frame, heavy brow, and rectangular jaw that she makes Shirley

Booth look like Gwyneth Paltrow. By all rights, Dressler should have

been too big, too thick for movies, excepting perhaps the Odessa Steps

sequence in The Battleship Potemkin; she's a dead ringer for the doomed, outraged giantess who marches her dead

child back up toward the marauding soldiers. Somehow, though, in the early 1930s, as the birdlike Lillian Gishes and Mary

Pickfords of the silent era passed their torch to the peppy comediennes and glamour goddesses of the studio era, Dressler

rose to the absolute top of her profession. More than just a comeback queen, having faded in the wake of antique triumphs

like Tillie's Punctured Romance (directed by Mack Sennett in 1914, and co-starring Charlie Chaplin), she emerged as a

veritable superstar, briefly without peer. Consider this extraordinary reminder from Matthew Kennedy's terrific biography: "At the time of her death in 1934, Dressler was the most beloved film star in America.

According to an August 1933 Time magazine cover story, her films then earned an average of $800,000 each—a sum far

exceeding the draw of all other stars. The honor of box-office champion was officially given to her in 1932 and 1933 by the

Quigley Publication and the Motion Picture Herald's nationwide poll, which asked 12,000 motion-picture exhibitors to

name movie stars with superior earning power. Dressler topped Jean Harlow, Joan Crawford, Clark Gable, Greta Garbo, and

Mickey Mouse. There were Marie Dressler puppets, dresses, fan clubs, and commemorative flowers."

All this for an actress whose alter ego in Min and Bill

calls herself an "old sea cow." Typically of Dressler's manner, in this

and other films, she utters the line in a tone that registers

toughness, good humor, resignation, lucid practicality, a fainter twist

of sour than you'd think, and an earnest but highly subliminal

invitation to Bill (Wallace Beery), her boarder and possible paramour,

to contradict her. He doesn't, but then, he needn't: the rich

relationship between this man and this woman is terse, tempestuous, but

palpably felt and fully realized. The title figures are not obviously

in love, at least not in an obviously romantic way, but they are fully,

crucially, almost unquestioningly implicated in each other's lives.

They share meals and confidences and barbs. They enjoy liquor together,

and nurse each other. They have great, terrible, rocking rows: just

watch how Dressler pummels the imposing Beery and knocks him all around

a room—and then goes after him with an axe, gutting

the door of the closet where he's hiding, in what is obviously not

a process shot. Most importantly, they are guardians and protectors of

Nancy (Dorothy Jordan), a teenaged girl whom Min has raised after her

loose, dypsomaniacal mother Bella Pringle (Marjorie Rambeau) left her

as a babe in Min's boarding house. When Bella sallies back into their

lives, Bill shares Min's alarm that Nancy may be taken away, but he's

also helplessly attracted to this svelte, easy figure. The status quo

of this ersatz, fish-smelling family won't stay the same, but how and

to whom will Nancy escape, especially now that boys have come calling?

Will defending Nancy turn Min against Bill? Is his fascination with

Bella a partial rejection of Min? Why is there a slapstick boat chase

in this movie, and how does Dressler glide so swiftly from that sort of

sequence to the stark poignance of Min walking home, kicking a can

along the sidewalk, uncorking huge emotions without seeming to let any

out, and avoiding cliché at almost every turn?

Min and Bill, in a deft and efficient 66 minutes, offers a semi-comic spin on the kind of dockside melodrama popularized

by Eugene O'Neill in works like Anna Christie (adapted to the screen the same year as Min and Bill, with Dressler

in the cast). Something about the wharfs, a perennial locale for late-20s and early-30s cinema, prompted actors, directors,

and other artists to crystallize strong, almost rough emotions within concise but deceptively layered story structures.

While Min and Bill is less visually poetic than something like Sternberg's The Docks of New York, director

George Hill's straightforward style nonetheless serves the material and the actors perfectly. Dressler and Beery clearly

connect with the audience and with each other in ways that modern movies rarely ask, and which even the greatest bygone stars

seldom achieved. The hefty, exaggerated muscularity of their acting, the very quality that might on the surface seem dated

and uningratiating, locates Min and Bill on a subtle, exciting, hugely entertaining, and era-specific intersection

between theater and film. Almost everything about Min and Bill is subtly, humbly impressive, and Rambeau's supporting

performance is a real livewire, years before the Academy got around to acknowledging second-tier roles. Thank goodness they

got it right with Dressler, though. In single moments or shots, her face may seem to work too hard, or her physique may imply

a short route into typecasting, but her presence, her choices, her humor, her energy, and her gravity are utterly distinctive,

and all to be savored.

#58: Suddenly, Last Summer

(USA, 1959; dir. Joseph L. Mankiewicz; cin. Jack Hildyard; with Montgomery Clift, Elizabeth Taylor, Katharine Hepburn,

Mercedes McCambridge, Gary Raymond, Albert Dekker, Mavis Villiers, Patricia Marmont, David Cameron)

(USA, 1959; dir. Joseph L. Mankiewicz; cin. Jack Hildyard; with Montgomery Clift, Elizabeth Taylor, Katharine Hepburn,

Mercedes McCambridge, Gary Raymond, Albert Dekker, Mavis Villiers, Patricia Marmont, David Cameron)

IMDb

Sometimes even the major, personality-shaping fixations in

our lives recede for a while, but then forcefully reassert themselves

at unexpected moments. Literally, in this one week, I am experiencing a

mini-revival of my Tennessee Williams fandom, on three wholly different

fronts. Professionally, as my students pass in their senior thesis

projects, I have pulled my own undergraduate thesis out of the

mothballs: a structurally daffy, theoretically promiscuous, but

mercifully unhumiliating argument about Williams' plays as

pre-Foucauldian parables of panoptical social regulation, taking Not About Nightingales

as the central text. In a public context, Warner Bros. has just released a seven-disc box-set of films adapted from Williams

plays: Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, The Night of the Iguana, The Roman Spring of Mrs. Stone, Baby Doll

(which is actually an original Williams screenplay), Sweet Bird of Youth (a slightly neutered version of one of my

favorite plays), and two DVDs devoted to A Streetcar Named Desire, which figured further

down on this list. Theologically, today is May 19, which was not Katharine Hepburn's birthday, but it was the day she often

cited as her birthday—May 19, 1909, rather than May, 12, 1907—in order to shave two years off of her age.

Suddenly, Last Summer features one of Hepburn's best and steeliest performances, and certainly her most gleamingly

villainous. She literally enters the movie from a great height, soaring down in a rococo elevator, spouting redolent

mythologies about herself and her dead son Sebastian—the ghostly, depraved Rosebud of this particular mystery. Now get

ready for this plot: Hepburn's fabulously venal Violet Venable has called one Dr. Cukrowicz (Montgomery Clift) to her eerie

palace in order to persuade him to lobotomize her niece Catharine (Elizabeth Taylor), whose first-hand account of Sebastian's

outlandish death has landed her straight in the booby-hatch. Catharine's story is

quite a whopper, pivoting on details like pedophilia, prostitution,

homosexuality, and cannibalism: it would seem that Sebastian has been

gobbled by a ravenous band of young Spanish street-hustlers. Being a

Williams play, this Guignol tale is, of course, a benchmark of truth.

Instead, it is high society and social institutions that are unmasked

as killing lies: the deceptive, carnivorous will of old-money

aristocracy, embodied by Hepburn's Violet and her garden of Venus

flytraps, and the buyable ethics of modern corporate medicine,

represented by the endowment-hungry trustees of Monty's hospital.

Granted, political content is not the first thing one might look for in

Gore Vidal's mad adaptation of Williams' play, itself as purple as a

low-hanging cluster of grapes. The script needlessly and distractingly

pads the sensational atmosphere with predictably googly-eyed sanatorium

scenes. Clift, recklessly sunk into this maelstrom of insanity, crosses

his arms and darts his pupils in several scenes as though he is barely,

quietly holding himself together, while his famous pal Liz Taylor

sallies forth with her lurid monologues without quite adding much to

them. Still, Suddenly, Last Summer fascinates almost as much as it entertains, which is tremendously. Director Mankiewicz, having helmed some

of the greatest Hollywood movies about dubious, contested tales (All About Eve, A Letter to Three Wives),

cleverly whets our appetite for the naked, bleeding truth, even as his

direction of the actors and his gamely bold production design make

clear that he is most interested in the nervy climate of repression and

panic that surrounds the breech-birth of a horrible family secret. When

Mercedes McCambridge, the most proudly perverse of 1950s character

actresses, shows up as a fluttering flibbertigibbet, the movie's fruity

compote gets even more aromatic and flavorful. It simmers enticingly,

and sometimes, gloriously, it boils right over.

In short, if it's camp you want, it's camp you'll get, as when Monty

gives a blond male nurse a visible once-over, or when Liz starts

struggling with a locked door in the wrong place at the wrong time,

triply imprisoned by an iron-barred causeway, an expressionist camera

angle, and a triangulated bra. The movie makes it so easy for

conservative culture vultures to tear away at it, like the flesh-eating

birds that feast on baby sea turtles in one of Hepburn's centerpiece

monologues. Tear they did: Suddenly, Last Summer sparked a bonfire of disgusted protest in 1959, but the movie, even more than the play, belongs in that beastly

menagerie with Faulkner's Sanctuary, Pasolini's Sal?, and Mary Harron's film of American Psycho,

aggressively vulgar works in which a hard, proud skeleton of social

critique and complex implication is nonetheless palpable, even to

viewers as green as I was at age 15, when I first saw the movie.

Floating between its scenes of family terrorism, pulsing beneath the

shiny enamel of Williams' lyrical prose ("Most people's lives—what are

they but long trails of debris, with nothing to clean it up but,

finally, death"), triumphing over the drag-revue flourishes like

Hepburn's emu-feather hat and Liz's perpetually breathy delivery ("We!

pro! cured! for! him!"), there is something remarkably formidable about

Suddenly, Last Summer. It makes you chuckle, sometimes against its own interests, but it also lingers like few "better" films ever do,

and in that way at least, it's a better Williams film than those bashfully catered affairs that Richard Brooks whipped up out

of Cat and Sweet Bird. Just you try flossing it from your mind.

#59: Bullets Over Broadway

(USA, 1994; dir. Woody Allen; cin. Carlo Di Palma; with John Cusack, Chazz Palminteri, Dianne Wiest,

Jennifer Tilly, Tracey Ullman, Jim Broadbent, Joe Viterelli, Mary-Louise Parker, Rob Reiner, Jack Warden, Harvey Fierstein,

Edie Falco, Debi Mazar)

(USA, 1994; dir. Woody Allen; cin. Carlo Di Palma; with John Cusack, Chazz Palminteri, Dianne Wiest,

Jennifer Tilly, Tracey Ullman, Jim Broadbent, Joe Viterelli, Mary-Louise Parker, Rob Reiner, Jack Warden, Harvey Fierstein,

Edie Falco, Debi Mazar)

IMDb

"I'm an artist!" John Cusack bellows in the first line of Bullets Over Broadway, the last Woody Allen movie that needn't

be embarrassed of such an opening. What is truly, wonderfully disarming about the film is that Cusack's David Shayne, for

all of his obviously Woody-ish mannerisms, doesn't sap the air out of the movie like most of Allen's recent alter egos have,

especially when Allen has played them himself. Sure, it's probably a flaw that the scenes in which David bellyaches to his

girlfriend (Mary-Louise Parker), agent (Jack Warner), and best friend (Rob Reiner) about the proper role of the artist make

so little impression. Still, these formulaic punchlines and underserved characters don't weigh against the movie because

Allen, for the first time since The Purple Rose of Cairo, aspires as much to entertain his audience as to sell his

ambitions or gnaw away at his philosophical obsessions. Don't get me wrong: I don't necessarily favor Woody's comedies

over his dramas, as higher entries on this list will verify. But Allen's humor can be so vivid and his direction so

encouraging to comic actors that it seems a shame he has become so parsimonious with those gifts. The fact that co-scripter

Douglas McGrath's own subsequent movies felt so weightless, in absolute contrast to Allen's crushing self-consciousness in

Deconstructing Harry and Match Point, implies that their partnership on this screenplay was an especially

inspired and well-timed stroke of luck. The movie also has a reasonably credible beginning, middle, and end, even if the

plot grows overly obedient to somewhat inane moral "arguments." Finally, I think it's Allen's best-looking movie since

Manhattan, achieving the kind of playful zest in its Damon Runyon interiors and pop-colored palette that his other

Depression-set movies have often nodded toward but never fully attained. Jeffrey Kurland's costumes are especially

marvelous, as giddy and plush with outrageous comic abandon as are the movie's dialogue and its performances.

But let's not bury the lead: Bullets Over Broadway lives, sparkles, even jubilates because of its dialogue and its

performances. Why does it feel a little embarrassing to say so? Perhaps mainstream film criticism places such exclusive

emphasis on words, story, acting, and character that it feels almost regressive to praise a movie so roundly in those terms.

But there it is, and happily so. The narrative conceit of David Shayne's turgidly sub-O'Neill script, God of Our Fathers,

is brilliantly borne out by such believably lumpen lines as "The days blend together like melted celluloid, like a film whose

images become distorted and meaningless"—a line, in fact, that wouldn't feel at all out of place amid the strenuous

solipsisms of Interiors (though, at least in that film's case, I take the solipsisms to be

purposeful). As the plot requires, not just Shayne's writing but his way of speaking is utterly shown up by the perfect,

vulgar concision of Chazz Palminteri's Cheech, who screams of David's play, "It stinks on fuckin' hot ice!" Dianne Wiest's

Oscar-winning turn as the boozy, stentorian Helen Sinclair remains the movie's most famous calling-card. Like the movie

itself, Wiest's broad overplaying yields so many dozens of delightful moments that you don't care how often the seams show

in what she's doing, how Helen is so obviously more of a joke machine than a character. Even the justly celebrated running

gag around the line "Don't speak!" is regularly surpassed by Wiest's camp modulations and leopard growls at other moments. I love how she

snares David's ego through well-calculated praise in a bar, parades him around the roof of her Manhattan apartment, and then

huffs out her love for the dark, empty theater where they rehearse with a perfectly pronounced, Hepburnian "Look! would

you look!" When David enters her apartment and complements her exquisite taste, her purring retort—"My taste is superb,

my eyes are exquisite!"—is almost literally killer. Indeed, her floridly self-conscious style of seduction,

previously unknown outside those species of insects that eat their young, is a gift that keeps giving, full of glorious,

histrionic silences in which Helen mentally assembles her next audition for the Baby Jane-ish role of herself.

But you know, as I've belly-laughed my way through sixth and seventh and eighth viewings of the movie, the frizzed,

helium-filled performance of Jennifer Tilly has come to rival Wiest's, revealing real creative ingenuity. Look how many of

her best scenes are delivered with her back to the camera, as when she lobbies in vain with David to protect the one speech

she has managed to memorize ("But I like to say it..."), or when, also on-stage, her fabulously flubbed exclamation "The

heart is labynthinine!" is somehow made even more uproarious by the perfect timing and ostrichy posture of her walk. But

wait! The single funniest bit of physical acting in the movie isn't Wiest's or Tilly's but Tracey Ullman's. Just

watch as Eden Brent, Ullman's own accelerated riff on actressy eccentricity, becomes the first among David's cast to publicly

endorse one of Cheech's dramaturgical tips. It's a one-second tour-de-force in a film that just brims with instants like

this. You can watch Bullets Over Broadway with the sound off and have a thrilling time. You can listen to it from

the next room and achieve total bliss. The fullness and variety of its pleasures still don't amount to Allen's best movie,

not even one of his best five—and bully for him for setting such a high bar. Still, of all of his pictures, I do think

Bullets is his most easily, frothily, and durably enjoyable.

#60: JFK and Nixon

(USA, 1991; dir. Oliver Stone; cin. Robert Richardson; with Kevin Costner, Sissy Spacek, Gary Oldman,

Tommy Lee Jones, Joe Pesci, Michael Rooker, Jay O. Sanders, Laurie Metcalf, Donald Sutherland, Kevin Bacon, John Candy, Jack Lemmon, Walter Matthau,

Ed Asner, Beata Pozniak, Sally Kirkland, Anthony Ramirez, Wayne Knight, Vincent D'Onofrio, Pruitt Taylor Vince, Dale Dye, Jim Garrison)

(USA, 1991; dir. Oliver Stone; cin. Robert Richardson; with Kevin Costner, Sissy Spacek, Gary Oldman,

Tommy Lee Jones, Joe Pesci, Michael Rooker, Jay O. Sanders, Laurie Metcalf, Donald Sutherland, Kevin Bacon, John Candy, Jack Lemmon, Walter Matthau,

Ed Asner, Beata Pozniak, Sally Kirkland, Anthony Ramirez, Wayne Knight, Vincent D'Onofrio, Pruitt Taylor Vince, Dale Dye, Jim Garrison)

IMDb // My Page

(USA, 1995; dir. Oliver Stone; cin. Robert Richardson with Anthony Hopkins, Joan Allen, James Woods,

J.T. Walsh, Paul Sorvino, David Hyde Pierce, Powers Boothe, Ed Harris, E.G. Marshall, Madeline Kahn, David Paymer, Bob Hoskins,

Larry Hagman, Mary Steenburgen, Tom Bower, Annabeth Gish, Marley Shelton, Corey Carrier, David Barry Gray, Tony Goldwyn,

Joanna Going, Peter Carlin, Edward Herrmann, Brian Bedford, Fyvush Finkel, George Plimpton, Tony Plana, Kevin Dunn,

Tony Lo Bianco, Dan Hedaya, Bridgette Wilson, Michael Chiklis, Saul Rubinek, John Diehl, Ric Young, Boris Sichkin)

IMDb // My Full Review

People often ask me when my addiction to movies began, and I think I'd have to trace it to the years 1990-92, when I was

growing up on an Army base in Hanau, Germany, where one of the most reliable and accessible entertainments for people my age

was the single-screen movie theater. Movies arrived from America on a 3-6 month time delay, which at the time only added to

their mysterious allure, since hype built for so long and under such different, more relaxed, and more reliable word-of-mouth conditions from the hypermediated

onslaught of today's advertising. Living in a foreign country with only one English-speaking TV station (commercial-free to boot)

further slowed the faucets of standard PR. These were also the years when my family bought our first VCR, so I could finally

see both old and new movies of my own choosing, and with relatively little cultural noise dictating my opinions about what I was

seeing. The only impediment on the theatrical side of things—a huge consideration then, though it seems now like another

life—was having to finagle admission into R-rated movies. The fellow who worked the ticket counter didn't

give me too much trouble despite disliking me, growling once that "you sure seem to have a lot of aunts and uncles" (read:

strangers in line who agreed to shepherd me inside). The only two times I really had a problem hurdling over the R-rating,

when the sleepy theater on cobblestoned Pioneer Kaserne suddenly sprang into high alert, were for Madonna: Truth or Dare,

which outraged my ardent fandom and confirmed the evident social panic about uninhibited women, and for

Oliver Stone's JFK. The censorious, highly disapproving vigilance that swirled around this movie was an altogether

weirder case to me. American talking heads only ever supply "sex and violence" as the Scylla and Charybdis waiting

to assail wayward youth, but neither appeared to be at issue in JFK. Granted, the theater staff did attempt to couch their quivering stinginess about

Stone's images in terms of gore, of all things: no teenager, ostensibly, could possibly handle those wrenching replays

and closeups of the Zapruder film, even though the predatory flayings in The Silence of the Lambs and the cheek-biting,

family-stalking, capsizing menace of Max Cady in Cape Fear had just come and gone without similar caveats. Synthesizing

the bizarrely fraught atmosphere at Pioneer with the cyclone of debate echoing from American media, I was perplexed as

to what particular candy, laced with exactly what barbiturate or perverting element, JFK was offering to its endangered, corruptible audiences.

I can't remember now if my parents were unavailable or just uninterested in JFK, but my brother (good man!), hooked

me up on the underground railroad with his high-school government teacher, and I was in. The movie totally blew my mind, as

the phrase goes, but without just circumventing or opiating it. JFK's unimpeachable technical brio and its breathless dicing

together of what feel like millions of film-fragments are enormous achievements in themselves. I can see where, as rhetorical

devices, and even more as historicizing methods, they would leave much to be desired, but to cite an axiom that somehow

always needs defending, JFK is not a legal brief but a movie—admittedly a movie with bullish designs on levering open

the locked and sealed government case files, but also, quite patently, a "movie-movie" whose

self-conscious flourishes of sound, music, montage, visual embellishment, changes in film stock, exaggerated characters, a

highly caffeinated supporting cast, and pivotal arias of exposition and deduction (Laurie Metcalf's, Donald Sutherland's,

and finally Kevin Costner's) all flagrantly announce the artifice and constructedness of what Stone has assembled. He and

his crack team of collaborating artists devise stunning visual and audio analogues not just of paranoia but of outraged collective justice and of the massive, wormy coral reef of history, with its

infinite chambers and pores, many of which never see the sunlight. Yes, it's a flawed film: Costner is too lightweight,

Sissy Spacek's perspective as the lonely and agitated wife is almost nothing when it could have been something, and every time

the film comes within a hundred feet of homosexuality, the performances, dialogue, and filmmaking all start stinking like

wilted Southern verbena. Still, in a strange way, the lapses of JFK have always corroborated what is artful and almost

frighteningly earnest about it: Stone works so fearlessly from the gut, with such unembarrassed fidelity to his sensibility,

that the warts-and-all pursuit of ugly truths feels truly impassioned in this film. Not for Stone the decorous boilerplates

of most courtroom dramas or tasteful liberal-historical tableaux, and almost single-handedly, JFK eliminated any need to

make excuses for detritus like Ghosts of Mississippi, half-efforts like Mississippi Burning, or even decoy denunciations

of invented crises, like the decidedly minor Guantánamo crisis in A Few Good Men. Stone already knows that

both literally and figurally, we can't handle the truth—we can't touch it, and we can't accept what we can't touch—but

he's able to use far more than foot-stomping speeches to register the point and its implications. In fact,

conjoined with JFK's scalpel-edged critique of mainstream historical record is an equally sharp dismantling of our most

naïve habits of image-reception. Not only does Stone recombine fresh and archival footage with the fervor of a mad geneticist, but

he gamely stages illustrated versions of Jim Garrison's conjectures as well as the Warren Commission's, and of several gradations

in between. Even when the script is one-sided, the film never is. JFK drives so many nails into the comortable

conflation of filmed imagery with reality, is it any wonder that the film was so willfully misunderstood?

As with the Minghella duo a few rungs down on this list, JFK stimulated new

appetites and ideas in my filmgoing which were even better rewarded by a subsequent effort from the same creative

team. I've already posted a full review of Nixon, but if you've got seven

hours free to watch the two films back to back, they remain fascinating companions. Whereas the coin of the realm in JFK

is its vertiginous scrim of lightning-historical collage, asserted as an inherently greater force than the individuals scurrying

around with their treacheries and truth crusades, Nixon

remembers that history is still shaped by people, and that the unease and extremes of history cycle backward as the groundwater

in our psyches and our private biographies. Again, some of Stone's touches are just too much: summits in China and in Texas and at J. Edgar

Hoover's poolside still feel like trips to the fruitstand. Still, the broad, stentorian strokes in the dialogue and the visuals

are plausibly illustrative of Nixon's mostly unsubtle grasp of his own life, and of what he was doing with everyone else's life.

The ensemble of actors feel more like a united organism, rather than a series of showy walk-ons, and by allowing us

more time and a slower pace to absorb the film's structure and its ironies, Nixon achieves what film biographies almost

never do: it proposes a complex, counter-intuitive, and intricate new idea about an extremely well-known figure, portrayed

against a detailed canvas of his intimates and his era. Nixon is almost certainly my favorite film about American politics,

but it's also my favorite film of a Shakespearean tragedy. That Shakespeare didn't happen to write it is the result only of

his living at the wrong time—a 400-year historical accident, though of course, in Stone's world, there are no historical

accidents.

As with the Minghella duo a few rungs down on this list, JFK stimulated new

appetites and ideas in my filmgoing which were even better rewarded by a subsequent effort from the same creative

team. I've already posted a full review of Nixon, but if you've got seven

hours free to watch the two films back to back, they remain fascinating companions. Whereas the coin of the realm in JFK

is its vertiginous scrim of lightning-historical collage, asserted as an inherently greater force than the individuals scurrying

around with their treacheries and truth crusades, Nixon

remembers that history is still shaped by people, and that the unease and extremes of history cycle backward as the groundwater

in our psyches and our private biographies. Again, some of Stone's touches are just too much: summits in China and in Texas and at J. Edgar

Hoover's poolside still feel like trips to the fruitstand. Still, the broad, stentorian strokes in the dialogue and the visuals

are plausibly illustrative of Nixon's mostly unsubtle grasp of his own life, and of what he was doing with everyone else's life.

The ensemble of actors feel more like a united organism, rather than a series of showy walk-ons, and by allowing us

more time and a slower pace to absorb the film's structure and its ironies, Nixon achieves what film biographies almost

never do: it proposes a complex, counter-intuitive, and intricate new idea about an extremely well-known figure, portrayed

against a detailed canvas of his intimates and his era. Nixon is almost certainly my favorite film about American politics,

but it's also my favorite film of a Shakespearean tragedy. That Shakespeare didn't happen to write it is the result only of

his living at the wrong time—a 400-year historical accident, though of course, in Stone's world, there are no historical

accidents.

Fly (USA/Canada, 1986; dir. David Cronenberg; cin. Mark Irwin; with Jeff Goldblum, Geena Davis, John Getz, Joy Boushel, David Cronenberg, Les Carlson)

Fly (USA/Canada, 1986; dir. David Cronenberg; cin. Mark Irwin; with Jeff Goldblum, Geena Davis, John Getz, Joy Boushel, David Cronenberg, Les Carlson) Not that anyone balks anymore when you take a critical stand on behalf of a Cronenberg film. Fatal Attraction was and is a different story: plenty