Cannes Festivals by Year:

Prizes, Juries, Favorites

Other Fests: Venice / Chicago

Stay tuned for more yearly indexes!

Browse Films by

Title /

Year /

Reviews

Nick's Flick Picks

Home /

Blog /

E-Mail

|

|

Cannes 1995: Jury Roundtable #1 / Click Here to Comment

Jury deliberations at the actual Cannes Film Festival are fiercely sequestered, with only a few pips and squeaks coming out during the final-day press conference that was instituted somewhere around the year Fahrenheit 9/11 won, mostly so Tilda could say to everyone, but mostly to Tropical Malady fans, "Don't worry—I totally handled this from the beginning." But here at Nick's Flick Picks, we're running a more transparent process, so I gathered the most vigorous participants in this mega-project to shoot the breeze about all the films, especially the Palme contenders, that we screened on Day 1, Day 2, Day 3, Day 4, and Day 5. Grab a rosé and join us at our beachfront table with the big umbrella...

NICK: We're about a third of the way through the Main Competition, and I doubt I'm the only person who can't shake the feeling that the programmers are saving the best stuff till later. Hopefully not too much later? I know it's rare to fire the big guns in the opening days, but I'm still befuddled on a few points. Why such a huge Competition bench of 24 titles if some are as manifestly negligible as Beyond Rangoon or Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea? Why such an emphasis on British cinema when it's hard to see what's boundary-pushing about these particular entries? And what in the world do we do with The City of Lost Children, which struck me as one of the most tantalizing prospects on the way in, particularly given its Opening Night spot, but somehow unfolds as both a series of loud bangs and a succession of listless whimpers? I'm not having a bad time, and some of these titles went down reasonably well with me. I'm just—I don't know—still waiting for the festival start? NICK: We're about a third of the way through the Main Competition, and I doubt I'm the only person who can't shake the feeling that the programmers are saving the best stuff till later. Hopefully not too much later? I know it's rare to fire the big guns in the opening days, but I'm still befuddled on a few points. Why such a huge Competition bench of 24 titles if some are as manifestly negligible as Beyond Rangoon or Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea? Why such an emphasis on British cinema when it's hard to see what's boundary-pushing about these particular entries? And what in the world do we do with The City of Lost Children, which struck me as one of the most tantalizing prospects on the way in, particularly given its Opening Night spot, but somehow unfolds as both a series of loud bangs and a succession of listless whimpers? I'm not having a bad time, and some of these titles went down reasonably well with me. I'm just—I don't know—still waiting for the festival start?

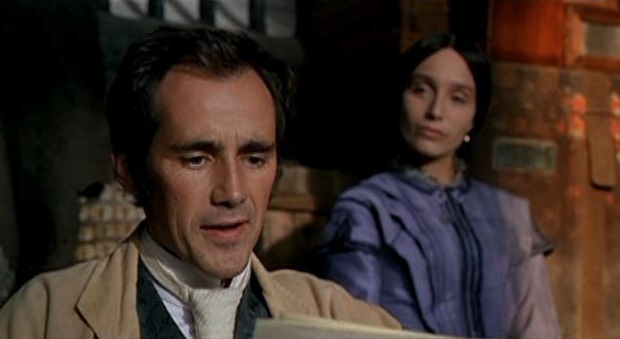

TIM BRAYTON: I'm not sure I can quite follow you all the way down into the depths of middlebrow despair. True, Carrington is re-inventing absolutely no wheels whatsoever, but given the potential for it to be perfectly perfunctory in every way (A biopic of a painter! Awards-friendly vagueness about alternative sexuality!), I think it's an impressively executed piece. Certainly, between them, Emma Thompson and Jonathan Pryce have a stranglehold on the Best Actress and Actor runs out of this first wave of movies, from my perspective. As to Angels and Insects, I might even go so far as to say that film does push boundaries a little bit—other people would know better than I, but I feel like depicting relatively explicit sex acts in a period film setting hadn't really been done to death yet. And those costumes! But for the most part, I'm right with you. Those two are easily the most impressive of this set of titles, and they're both much more what I'd expect to see in the lower range of quality than upper for a major festival competition.

It doesn't help that out of seven titles, my strongest reaction by far has been to Beyond Rangoon, a staggering chain of misjudgments. There's an almost comic level of ineptitude in the the acting and the way flashbacks are mashed into the main plot; it's a Very Noble Prestige Movie that starts going absurdly wrong from the first beat and never recovers itself. Boring competency is one thing, but whatever logic resulted in this trainwreck getting a Cannes berth is totally undetectable to me. It doesn't help that out of seven titles, my strongest reaction by far has been to Beyond Rangoon, a staggering chain of misjudgments. There's an almost comic level of ineptitude in the the acting and the way flashbacks are mashed into the main plot; it's a Very Noble Prestige Movie that starts going absurdly wrong from the first beat and never recovers itself. Boring competency is one thing, but whatever logic resulted in this trainwreck getting a Cannes berth is totally undetectable to me.

AMIR SOLTANI: We are a third of the way through the Competition lineup and I'm a third of the way through Carrington, having now tried on three separate occasions to press on to the end. Alas, at the risk of undermining my jury credentials, I have to admit that we're just not meant to be. My natural aversion to this genre, era and "type" of film aside, I find Carrington very poorly edited, not just because of the broken links between the scenes—the dots are just beginning to connect when I begin to check my watch—but because even within individual sequences, emotional relationships between characters and causal links between events are undermined by the juxtapositions. A certain je ne sais quoi is off-putting from the get-go.

Beyond Rangoon isn't any likelier to win my Palme vote. It's never a good sign when a film starts with a white character in a foreign land who within minutes spells out, literally, that she's in the "Exotic East." Between the film's poor understanding of the region's politics, its on-the-nose allegories, all the cheesy emotional catharses and the absurdly unnecessary voice-over narration, it's quite baffling that this film was even considered for the main competition.

And don't even get me started on The City of Lost Children! My note sheet from my screening of the film isn't helping me find anything positive to say about it, as it comprises only the single line, "It is virtually impossible to connect with this on any level." It has all the crazy antics of Amélie, but without the flowery brightness, the bittersweet sentimentality, or the humanity. Of course, I don't know that yet, because it's 1995. A few days into the festival, I think it's safe to say my favourite film is a non-competition Iranian entry, Jafar Panahi's debut feature The White Balloon. Of course, he's aided tremendously by the efficient and poignant screenplay written by Kiarostami, but I think there's enough here to suggest that he has a long career ahead of him and that in 20 years, this will have become the most enduring of the films we've seen so far. And don't even get me started on The City of Lost Children! My note sheet from my screening of the film isn't helping me find anything positive to say about it, as it comprises only the single line, "It is virtually impossible to connect with this on any level." It has all the crazy antics of Amélie, but without the flowery brightness, the bittersweet sentimentality, or the humanity. Of course, I don't know that yet, because it's 1995. A few days into the festival, I think it's safe to say my favourite film is a non-competition Iranian entry, Jafar Panahi's debut feature The White Balloon. Of course, he's aided tremendously by the efficient and poignant screenplay written by Kiarostami, but I think there's enough here to suggest that he has a long career ahead of him and that in 20 years, this will have become the most enduring of the films we've seen so far.

IVAN ALBERTSON: It just wouldn't feel like the mid-'90s without a preponderance of middlebrow British films. I, for one, think they could've gone further. Could they not find room for Cold Comfort Farm? Were Persuasion and A Month by the Lake not ready in time? I have to assume Jeanne Moreau and Helena Bonham Carter are neighbors or something—otherwise I cannot account for the absence of Margaret's Museum.

I concur with everything you said, Nick and Tim, save for the strength of Carrington's present grip on the acting awards. I'm not sure Angels and Insects would work as well as it does without Mark Rylance and Kristin Scott Thomas. Rylance expresses so much with his watchful eyes, nailing the subtle difference between timidity and frustration without downplaying his animal nature. While neither of these films is pushing the medium forward, I find them both quite emotionally sophisticated. They have an unusually clear-eyed view of desire as something essential that governs our behavior without ultimately being very meaningful. I like the disjointed editing in Carrington for precisely this reason, Amir. It reinforces how people change over time, how a jilted lover might throw a fit one day and sit down the next for a more level-headed reckoning (have you gotten there yet?). It circumvents biopics' big problem with time by treating life as just a string of relationships; it helps greatly to have the central bond as a through-line. In many ways, I respect this modest approach more than the gauntlet throw. It doesn't bolster Cannes as the site of groundbreaking cinema, but it's certainly more likely to succeed. I concur with everything you said, Nick and Tim, save for the strength of Carrington's present grip on the acting awards. I'm not sure Angels and Insects would work as well as it does without Mark Rylance and Kristin Scott Thomas. Rylance expresses so much with his watchful eyes, nailing the subtle difference between timidity and frustration without downplaying his animal nature. While neither of these films is pushing the medium forward, I find them both quite emotionally sophisticated. They have an unusually clear-eyed view of desire as something essential that governs our behavior without ultimately being very meaningful. I like the disjointed editing in Carrington for precisely this reason, Amir. It reinforces how people change over time, how a jilted lover might throw a fit one day and sit down the next for a more level-headed reckoning (have you gotten there yet?). It circumvents biopics' big problem with time by treating life as just a string of relationships; it helps greatly to have the central bond as a through-line. In many ways, I respect this modest approach more than the gauntlet throw. It doesn't bolster Cannes as the site of groundbreaking cinema, but it's certainly more likely to succeed.

I figured I would have to defend my distaste for The City of Lost Children, but I guess I'll have to wait until I serve on the 1995 (Speculative) Fantastic Fest Jury.

ALEX HEENEY: I watched Angels and Insects on the heels of binge-watching Wolf Hall. Seeing Mark Rylance suddenly fresh-faced and 20 years younger was jarring. I didn't like Angels nearly as much as I'd expected to given how much I like all of the people involved: I'll watch Rylance and Scott Thomas in anything, and I'd follow an A.S. Byatt adaptation anywhere. I agree with Ivan that those two would be my picks for Best Actor and Best Actress at this stage. Rylance is such an expressive actor. I'm a little disappointed that KST is playing yet another uptight British character, but I think I've been spoiled in the intervening 20 years by her renaissance as a French actress. I know we're supposed to find the family Rylance marries into to be repulsive, but his wife, especially, was so insufferable that I found she greatly impeded my enjoyment of the film. Nevertheless, I did appreciate the way Haas embraced ritual. The camera panning from Rylance's bedroom door to the door that connects his room to his spouse's each night was a constant source of suspense. I did find it interesting that Scott Thomas went straight from this film to narrating Microcosmos, a documentary about insects, the following year. ALEX HEENEY: I watched Angels and Insects on the heels of binge-watching Wolf Hall. Seeing Mark Rylance suddenly fresh-faced and 20 years younger was jarring. I didn't like Angels nearly as much as I'd expected to given how much I like all of the people involved: I'll watch Rylance and Scott Thomas in anything, and I'd follow an A.S. Byatt adaptation anywhere. I agree with Ivan that those two would be my picks for Best Actor and Best Actress at this stage. Rylance is such an expressive actor. I'm a little disappointed that KST is playing yet another uptight British character, but I think I've been spoiled in the intervening 20 years by her renaissance as a French actress. I know we're supposed to find the family Rylance marries into to be repulsive, but his wife, especially, was so insufferable that I found she greatly impeded my enjoyment of the film. Nevertheless, I did appreciate the way Haas embraced ritual. The camera panning from Rylance's bedroom door to the door that connects his room to his spouse's each night was a constant source of suspense. I did find it interesting that Scott Thomas went straight from this film to narrating Microcosmos, a documentary about insects, the following year.

I also agree with Tim about Angels and Insects being boundary-pushing for its depiction of Victorian-era explicit sex. The sexually open nature of both Angels and Carrington—Toto, we ain't in Merchant Ivory territory anymore—is the best reason I can come up with for why these were selected in Competition, aside from the sheer force of British acting talent. The films are otherwise, I'd agree, fairly mediocre. But I do agree with Ivan's assesment of Carrington as a whole: it may not be groundbreaking cinema, but it's still a thoughtful film.

I had to turn off The City of Lost Children after 20 minutes, no longer able to bear this assault on my senses, from the stentorian din to the incomprehensible plot. Not even Jean-Paul Gaultier's inventive costumes could save it. I suppose if this is what it took to allow Jeunet to eventually channel his creativity into a more playful and emotionally resonant film like Amélie it was worth it, so long as I don't have to watch it. This strikes me as the sort of film that would have gotten a lot of walkouts. Or, if people had smartphones in 1995, the Grande Théâtre Lumière would have had a distinct phosphorescent glow from all the people trying to relieve their boredom. Or perhaps press would have broken their "I'll walk out 10 minutes before it ends and still review it" rule and walked out 40 minutes in, yet still have the gall to review it. I had to turn off The City of Lost Children after 20 minutes, no longer able to bear this assault on my senses, from the stentorian din to the incomprehensible plot. Not even Jean-Paul Gaultier's inventive costumes could save it. I suppose if this is what it took to allow Jeunet to eventually channel his creativity into a more playful and emotionally resonant film like Amélie it was worth it, so long as I don't have to watch it. This strikes me as the sort of film that would have gotten a lot of walkouts. Or, if people had smartphones in 1995, the Grande Théâtre Lumière would have had a distinct phosphorescent glow from all the people trying to relieve their boredom. Or perhaps press would have broken their "I'll walk out 10 minutes before it ends and still review it" rule and walked out 40 minutes in, yet still have the gall to review it.

Despite Stanford's otherwise excellent DVD library collection, I couldn't find Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea and I skipped Beyond Rangoon after hearing Nick's assessment, so I'm not as pessimistic about this year's selection as I could be at this point. Here's hoping it just took a few days for the festival to start revealing its gems!

TIM: I'm exactly in the opposite corner from Ivan: I had the sense that if anybody was going to go to bat for The City of Lost Children, it was going to have to be me. And that's not a place I really want to be in, because I certainly don't love it. It suffers immensely from the existence of Delicatessen before it and Amélie after it—not to mention the then 10-year-old Brazil being basically the same movie with more intellectual goals than just exclaiming, "We have baroque sets!" Even so, there's a bonkers commitment on display that I admire. It certainly goes all-in about following all of its ideas down whatever rabbit holes come up, and the filmmakers palpably love the grotesque world they're playing around in. There's not a single shot that doesn't feel completely intentional, even if that intent isn't always what I'd have preferred. It's cheating to say this, because it's the only film out of this batch I've seen before, but I'm fairly confident in predicting that I'll still remember specific images from this movie long after Carrington has receded in memory to just "that Emma Thompson thing," even if the latter is an objectively better film.

And hey, so nobody's talking about Jefferson in Paris. Too much mediocrity to even name it?

NICK: Jefferson in Paris has a hard time even talking about itself. The movie at least evokes a rarefied milieu of French-US relations and cultural crossover at a very specific moment in history, among other grudging compliments I would pay to it. But it's an awfully airless, occasionally lumbering affair, and it's odd how the prologue rushes to cast the Hemings-Jefferson legacy as its central concern, only for Jhabvala's script to postpone for over an hour any further delving into that sordid, complex history. Jefferson never quite finds its voice in relation to that still-volatile legacy, even if it's a somewhat more earnest stab than Beyond Rangoon's egregious Western narcissism or Between the Devil...'s ambivalence about truly confronting daily realities for a 10-year-old Chinese girl scraping together a subsistence amidst a field of rough-edged men. "I know," the film seems all too quick to say, "let's just make it a winsome fable!" But they're all clinkers. NICK: Jefferson in Paris has a hard time even talking about itself. The movie at least evokes a rarefied milieu of French-US relations and cultural crossover at a very specific moment in history, among other grudging compliments I would pay to it. But it's an awfully airless, occasionally lumbering affair, and it's odd how the prologue rushes to cast the Hemings-Jefferson legacy as its central concern, only for Jhabvala's script to postpone for over an hour any further delving into that sordid, complex history. Jefferson never quite finds its voice in relation to that still-volatile legacy, even if it's a somewhat more earnest stab than Beyond Rangoon's egregious Western narcissism or Between the Devil...'s ambivalence about truly confronting daily realities for a 10-year-old Chinese girl scraping together a subsistence amidst a field of rough-edged men. "I know," the film seems all too quick to say, "let's just make it a winsome fable!" But they're all clinkers.

I co-sign a lot of previous compliments to Angels and Insects and Carrington, and probably feel closest to Ivan's takes on both movies. The former conjures the sulfurous atmosphere of inbred aristocracy with gleeful nastiness in some scenes and an odd, impressive sympathy in others; it's an interesting balance, and Scott Thomas gives my favorite performance in any of the Competition movies thus far, slicing like a shark's fin through that stifled, hypocritical atmosphere. She never loses sight of her character's own form of suffocation, even as she conveys her thoughts rather freely. I like the narrative arrythmia of Carrington and its almost mosaic approach to story and biography, even though it's hard to gauge (as our conversation has proved) which viewers will cotton to that strategy and which won't. These were two of the films I had in mind when I said up top that I actually like some of these early premieres, even if they make a rather subdued case for themselves as Competition entries. In that regard, I take Ivan's point about the value of modesty.

My other favorite in this group is Sharaku, which has as much courage of weird conviction as The City of Lost Children without being quite so grandiose. It also emits comparable impulses to Carrington's in challenging "biopic" templates, in telling a highly speculative story about someone whose work has lingered but whose life is almost completely lost to history. I liked how the script's structure means Sharaku keeps having to edge his way into his own movie, which is dominated so often by his foil and rival Utamaro. I also dug the perversity and gusto of several images. The opening scene (foot, ladder, blood) was even more gripping to me than Jeunet's funnyhouse Santa Clauses, though I liked those, too. I was impressed that Shinoda kept us guessing ever afterward what kind of game he was playing: long, short, literal, subliminal, biographic, atmospheric. It's the movie lingering most with me, even though in many ways I understood it the least. Anyone else taken by this one? My other favorite in this group is Sharaku, which has as much courage of weird conviction as The City of Lost Children without being quite so grandiose. It also emits comparable impulses to Carrington's in challenging "biopic" templates, in telling a highly speculative story about someone whose work has lingered but whose life is almost completely lost to history. I liked how the script's structure means Sharaku keeps having to edge his way into his own movie, which is dominated so often by his foil and rival Utamaro. I also dug the perversity and gusto of several images. The opening scene (foot, ladder, blood) was even more gripping to me than Jeunet's funnyhouse Santa Clauses, though I liked those, too. I was impressed that Shinoda kept us guessing ever afterward what kind of game he was playing: long, short, literal, subliminal, biographic, atmospheric. It's the movie lingering most with me, even though in many ways I understood it the least. Anyone else taken by this one?

IVAN: While I appreciate Sharaku's general avoidance of hand-holding, I found it to be lacking a definite narrative strategy (which is a fancy way of saying I was kinda bored). I may be a less generous viewer than you, Nick, but the absence of cohesion felt very much in keeping with the biopic tradition, even though, as you said, the film's interest extends beyond one man's life. Making Sharaku just one player in the ensemble is an interesting choice but not one Shinoda is fully committed to. In the second half, as if making up for lost time, Shinoda builds many scenes around displays of his artistic integrity and discussion of his greatness; the one where somebody asks, "Will the world be changed because of his paintings?" offered solid proof that the film was not, in fact, too refined for me to grasp. Still, he never emerges as a strong character. His relationship with the geisha, for example, is barely sketched in, especially given how important it turns out to be. There were definitely touches I liked—the early theatre scenes, where interruption is common and injury fictionalized—but they felt pretty anomalous.

Sharaku is still far more unified than Jefferson in Paris, which attempts a little bit of everything without doing any of it well. The script is just unforgivably scattered, as if Jhabvala read an encyclopedia entry (hey, it's 1995) and couldn't bear to leave or flesh anything out. Even worse, her characters always seem to be offering crudely articulated hot takes on slavery, nationhood, and even love. Ivory doesn't do the dialogue any favors by settling for performances either superficial (Nolte) or embarrassingly affected (Newton, Paltrow). It never feels like more than a staged reading.

TIM: As, I think, the only other person to have seen Sharaku, I'll chime in to say I'm pretty squarely between Nick and Ivan, though facing in Ivan's direction, perhaps. The first hour, I was absolutely where Nick was: the ellipses felt bracing and even more suggestive of the society where the film takes place than exposition would. I do think it's a bit of a conventional biopic technique, but it's the biography of "the cultured society of Edo-era Japan", rather than "this one guy Sharaku". Which I guess makes it unconventional. In the second half, though, it starts to hit all of the exact run-of-the mill notes that I'd seen none of prior to that: the big emotional stresses in the scene where He Makes His Most Famous Masterpiece, the moment where his rival admits to an empty room, "I could never make this painting," etc. And that gets increasingly uninteresting, particularly since the elliptical structure in the beginning makes it hard to feel like we're invested in the characters, as Ivan mentioned. But I think it's the most beautiful and most unusually-shot film in this first wave, so that's a plus. TIM: As, I think, the only other person to have seen Sharaku, I'll chime in to say I'm pretty squarely between Nick and Ivan, though facing in Ivan's direction, perhaps. The first hour, I was absolutely where Nick was: the ellipses felt bracing and even more suggestive of the society where the film takes place than exposition would. I do think it's a bit of a conventional biopic technique, but it's the biography of "the cultured society of Edo-era Japan", rather than "this one guy Sharaku". Which I guess makes it unconventional. In the second half, though, it starts to hit all of the exact run-of-the mill notes that I'd seen none of prior to that: the big emotional stresses in the scene where He Makes His Most Famous Masterpiece, the moment where his rival admits to an empty room, "I could never make this painting," etc. And that gets increasingly uninteresting, particularly since the elliptical structure in the beginning makes it hard to feel like we're invested in the characters, as Ivan mentioned. But I think it's the most beautiful and most unusually-shot film in this first wave, so that's a plus.

NICK: Okay, I was a little bored by Sharaku, too. You beat it out if me. But transfixed as well!

Looking forward to seeing you all at our next round of 8:30am Palais screenings, in which Ken Loach teaches us what's wrong with Stalinism, Theo Angelopoulos surveys what's wrong in the Balkans, and Larry Clark investigates what's really super-wrong with our youth. But before we sign off, any passionate statements one way or the other about any of the early sidebar showings? Amir already stumped for The White Balloon, which rose to the top of much Cannes coverage at the time. I agree it's a winsome, appealing tale with a chastening wisdom about human error of all kinds. I already knew that I want to be buried with a copy of Georgia and that I'll just never see as much in The Usual Suspects or To Die For as many others do, all of which I just reconfirmed. Among my first-time viewings, I was most pleasantly surprised by Heavy, a rich and maturely compassionate debut from James Mangold; the kickily structured Mute Witness, about a makeup artist who cannot speak, trapped overnight in a Russian film studio where she's just observed a brutal murder; and the closing sequences of Unstrung Heroes, which take that odd, eccentrically engaging dramedy out on an uncommonly moving note. If that strikes you as a weirdly Anglo-dominated list, it was definitely that kind of Cannes.

IVAN: Well, I would bury myself with a 35mm print of Georgia if a) I was sure one existed, and b) it didn't deprive future rep audiences of discovering it. Not to screw around with a can of worms, but I see Georgia like Georgia the singer—modestly, effortlessly soulful—and other movies about sibling rivalry or substance abuse like Sadie—shrill and unduly convinced of their own greatness). Yet the previous statement is reverent of Georgia and harsh to Sadie in a way the film never is. Grosbard is always sympathetic to Sadie's jealousy and ambition and even finds humor in her self-destructive tendencies. His generosity extends to every major character, allowing several equally valid perspectives on Sadie to coexist. This is a rare film that makes me laugh consistently but requires a breather to sit with the depths of Sadie's despair (for me, in the car after "Take Me Back"). It's probably good Georgia wasn't selected for Competition, for it would feel disingenuous not to give it three or four awards. IVAN: Well, I would bury myself with a 35mm print of Georgia if a) I was sure one existed, and b) it didn't deprive future rep audiences of discovering it. Not to screw around with a can of worms, but I see Georgia like Georgia the singer—modestly, effortlessly soulful—and other movies about sibling rivalry or substance abuse like Sadie—shrill and unduly convinced of their own greatness). Yet the previous statement is reverent of Georgia and harsh to Sadie in a way the film never is. Grosbard is always sympathetic to Sadie's jealousy and ambition and even finds humor in her self-destructive tendencies. His generosity extends to every major character, allowing several equally valid perspectives on Sadie to coexist. This is a rare film that makes me laugh consistently but requires a breather to sit with the depths of Sadie's despair (for me, in the car after "Take Me Back"). It's probably good Georgia wasn't selected for Competition, for it would feel disingenuous not to give it three or four awards.

Continue on to Jury Roundtable #2 ...

|

|